On a rare sunny day in May, I sit down with Catarina Vieira, a young Portuguese woman campaigning to be a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) in the Netherlands. We meet in the cafe of a cinema in Hilversum, the town where she is standing for election. The popping primary colours of the cafe match Vieira’s vibrant personality. Two weeks away from election day, she remains calm and approachable, stopping to chat to a member of the public on her way over to me.

“I did another interview this morning. I should’ve held a press conference,” she jokes.

At 27 years old, she is the youngest person standing for Groenlinks-PvdA, the party that won the most Dutch seats in the EU elections. This is a fusion between the Dutch parties Groenlinks (Green left) and PvdA (Labour Party). This isn’t only her first time running for the European Parliament, it’s her first time ever running as an elected official – she has been a Groenlinks delegate to the European Green Party since 2022.

“I’ve always felt European. I love Portugal and I’m very connected to my region, but I’ve always felt at home in the EU,” she says with a smile.

The average age of an MEP is 54 years old, according to recent data from the European Parliament. “When it comes to the representation of young people in European politics, a lot needs to change. Political parties and the way they’re organised has a lot to do with that.”

We speak about the barriers for young people engaging in politics. The European Parliament is one of seven main European institutions with more than 30 decentralised agencies spread across the union. “The EU is complicated. That doesn’t make for an easy to understand process. If you don’t understand it, how can you be interested in it?”

Those who migrated with EU citizenship can stand as an MEP, but this privilege has not yet been awarded to those who migrated from outside of the EU or asylum seekers. While she herself doesn’t place much weight on it, she has struggled with the perception of her identity since moving to the Netherlands. “My identity is such a question mark. In Portugal it’s clear, here it depends on who you ask.”

Although Vieira migrated to the Netherlands from Portugal, she emphasises that her migration story was more straightforward than others. “Mine was very easy, I had a university degree, I didn’t have to apply for a visa. Is that representative of people with refugee status? No. So, how do I support those people? How can I best serve the people whose migration stories are different from mine?”

Not being a Dutch national provided some difficulties during her campaign. “I didn’t get as much pushback as I expected to, but I have been asked the question ‘How are you going to represent a country you weren’t born in?’. To them I would say, no I wasn’t born here, but I’ve been here for seven years and I have no plans to move anywhere else.”

There are 704,000 non-Dutch EU citizens living in the Netherlands as of 2023. Thanks to freedom of movement rights, many EU citizens live, work and study abroad. “There have been calls to address this and create transnational MEPs. That hasn’t happened yet, so it’s the job of MEPs to advocate for these people living abroad.” Vieira has been doing this, pushing for outreach events to EU citizens alerting them to the deadline for voting registration. Her party welcomed her suggestions.

From Portugal to Politics

Vieira was born in the Azores, an autonomous island region of Portugal. She gained her first interest in politics at school, becoming involved in her local youth parliament, but never thought of it as a career at this point in time. At 18 she moved to Lisbon to pursue her studies in international relations.

Growing up, she says she wasn’t necessarily interested in participating in politics. “In Portugal, I was interested in politics, but I wasn’t active. It was more injustice I was taken by. I’m someone who really cares if things are fair,” she tells me.

“I feel like it is confusing to navigate politics, and it was hard for me. It’s hard to choose a party, commit to it, and be associated with that party.” She explains the precarious nature of aligning yourself with one political party in Portugal. “In Portugal, due to the culture, I was also worried about what a future employer might think if I associated myself publicly with a party,” explaining her hesitancy to engage in Portuguese politics.

So what was different about Dutch politics? After moving to the Netherlands in 2017, she found herself away from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. For her, this was a catalyst to becoming politically active. “Because the borders were closed, and there were no flights to go home, something clicked. I thought ‘you are here, this is your society, this is your prime minister making the decisions and the rules. If you want to make a change, it’s going to have to be here, not in Portugal.’”

Vieira is convinced that engaging young people in EU politics is not a lost cause. In the 2019 EU elections, the youth vote helped boost the election turnouts across the continent, with 42% of people aged below 25 showing up at the ballot box. “There are those that are really actively engaged in politics, and those that the only interaction they have with politics is through TikTok.” Vieira’s campaign has included holding talks in schools and being active in her local community. However, much of the campaigning also takes place on social media.

Being a woman who migrated to the Netherlands, she braced herself for backlash. “Before I became a candidate I wasn’t on TikTok or Instagram. The scariest thing for me was opening up my social media. Knowing how women and people from a migration background in politics are treated, there was something very scary about saying ‘yes, I volunteer for this.’”

She tells me that both she and her party had experienced negative comments on TikTok and X. “I’ve seen some stuff about my nationality, about me not being Dutch. Things like ‘speak Dutch, don’t speak English.’”

More concerning comments have been directed towards others. She points out that the nature of the comments she receives is less threatening than some of her fellow candidates. “I noticed that for candidates with Moroccan and Turkish backgrounds there can be so much hate directed towards them.”

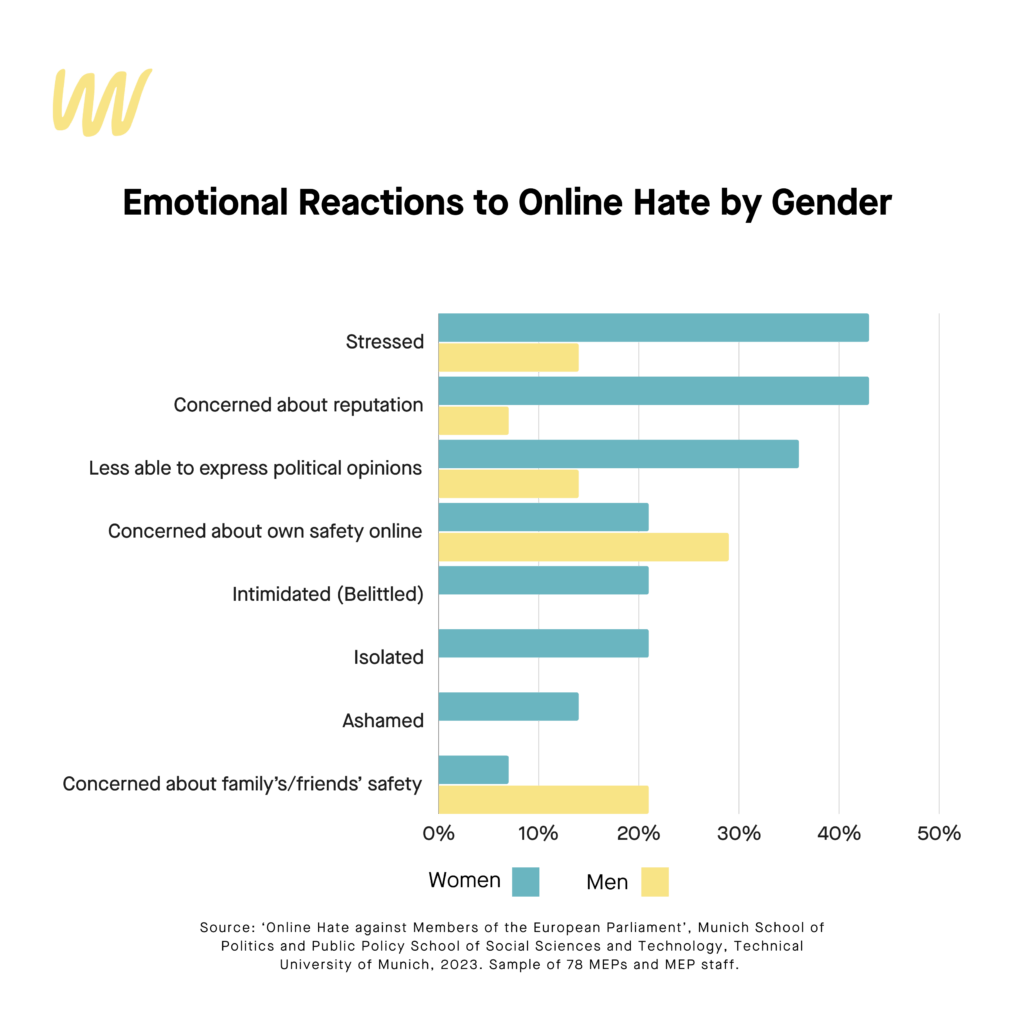

Viera’s experience of being attacked online is a well documented phenomenon. A 2023 survey from the Technical University of Munich revealed that both male and female MEPs receive abusive messages online. However, what the study found was that online hate placed a higher emotional burden on female MEPs. Women who experienced attacks were more likely to feel stressed, intimidated or belittled than their male counterparts. They also reported feelings of shame and social isolation after attacks, which were not expressed by male MEPs interviewed.

Opening herself up to public scrutiny was not a decision that she took lightly. “I’m aware of the narratives circulating from the far right about people on the left. I became afraid of what I am choosing for myself by standing for a left-wing party.”

Luckily she was able to go to other female MEPs for support. “What helped me was speaking to Kim van Sparrentak, an MEP for Groenlinks-PvdA, who was elected at 29 years old,” Vieira explains. “She has people targeting her online, but she reassured me that she does have a life, she has time to see her girlfriend and time to be herself as well as being a politician.”

These attacks deter women and other migrants from entering politics, which is why organisations like The Network of Migrant Women have created a manifesto for the EU elections. This set out 10 key recommendations for MEPs to advocate for migrant women and asylum seekers, such as not making women who reunify with their family dependent on their spouse for their legal status. Resources like this manifesto are a starting point for Vieira and other candidates to advocate for refugees, hopefully paving the way to more migrants becoming involved in politics.

Although Groenlinks-PvdA won the most seats, whether or not she will sit in parliament is currently unclear. Regardless of whether she is elected as an MEP, Vieira has been grateful she has been able to stand in the country she now calls home. She encourages others to do the same. “At the end of the day, that’s really the message I’d like to pass on.”

Since the publication of this article Catarina Vieira has been elected as an MEP for Groenlinks-PvdA in The Netherlands.