Chairs carry our bodies in all sorts of situations. A meagre metal structure squeaks in the nervous silence of waiting rooms, whereas a colourful formica chair invites guests to the dinner table. A cosy armchair lets you sink into its cushion, and a light foldable stool comes in handy to holidaying campers and weary gallery visitors alike.

Throughout their lives, modern humans spend a lot of time with their buttocks spread over the flat surface of a chair. According to a recent study, Germans spent an average of 8.5 hours per day sitting in 2021, an hour more compared to 2018. To take the weight off our feet is a natural urge. Yet our sitting habits do not reflect the needs of our bodies.

“Some chairs make you feel you’re too big for them,” says Bethan Griffiths, a historian in Berlin, as she sits down on a narrow metal chair in the garden of a café. “They dig into your legs and back and squeeze you like a pair of ill-fitting jeans.” Griffiths regularly walked in her previous job as a tour guide. Since working in research, she spends her workdays on chairs, which often seem ill-suited for their purpose. Not fitting in furniture makes her feel doubly uncomfortable: “As if it wasn’t made for people like you. If you don’t fit in the furniture, then you don’t fit into your surroundings either.”

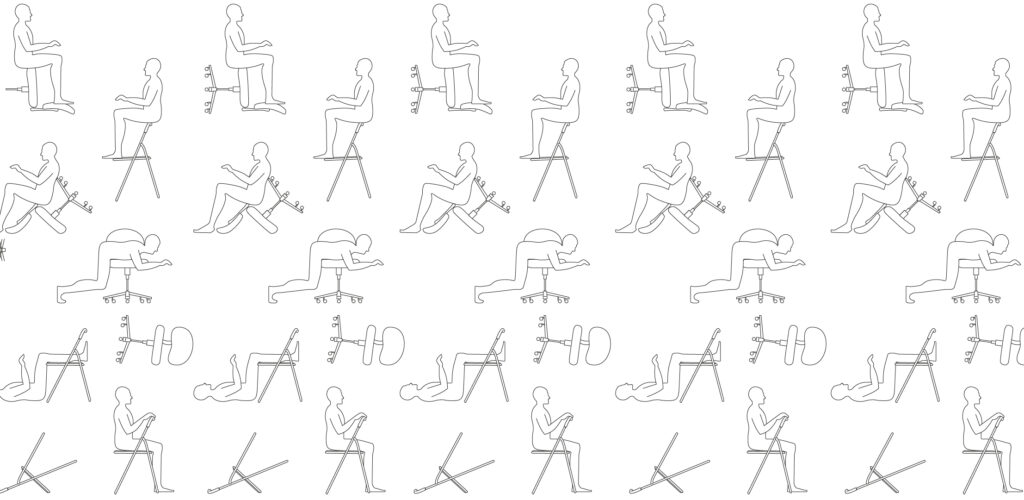

Think away the support that chairs offer, and you will get a human body in a position that seems at odds with its shape and form. According to Galen Cranz, a professor at the College of Environmental Design at the University of California in Berkeley, chairs have little to do with our biology. Our bodies are, by design, meant to be active, yet chairs work to the contrary. Sitting furniture attempts to contain rather than facilitate body movements. This leads to the discomfort we feel when we sit over prolonged periods of time.

Western bathroom habits may offer insights into the paradox of sitting. Public toilets in ancient Rome were long benches with key-shaped holes. In medieval Europe, the rich and powerful throned on a commode—a piece of furniture with a seat and a lid concealing a pot for the waste. The water closet dates to 16th-century England, and although it took until the 1880s for toilets to become connected to the sewer system, the chair-like structure has remained more or less the same to this day. In recent years, however, the inherited sitting posture has come under scrutiny, and toilet stools that encourage squatting to facilitate bowel movement have grown in popularity. Despite the proven health benefits of that position, many still prefer to sit.

As Cranz argues in her book, The Chair: Rethinking Culture, Body and Design, chair-sitting has a long tradition. Wooden furniture, in shapes remarkably similar to modern-day chairs and stools, was charged with symbolism in ancient Egypt. The Greeks and Romans sat or reclined on various types of furniture, and in Medieval Europe, most people sat on the floor, and chairs were reserved for the affluent. By way of colonialism, chairs spread across the world and became a symbol of westernisation, existing alongside more traditional forms of sitting such as squatting or sitting cross-legged on the ground. “Chairs have become a way of displaying hierarchy in complex societies,” Cranz explains. Whilst postures, including sitting, have symbolic meanings in all cultures, the western chair-sitting habit is linked to notions of status, power, and dignity. As opposed to the ground, a chair usually holds one person at a time, thereby emphasising their existence as an individual. From this perspective, floor-sitting was deemed primitive, uncivilised and unhygienic.

Connotations of power are at work in language, too. The word “chair” comes from the Greek kathédra (kata, “down” and hedra, “seat”) and its Latin successor cathedra, which in turn came to signify the bishop’s seat in early Christian basilicas. In English, an academic strives to hold a university chair (cattedra in Italian), a chairperson presides over an organisation or a committee, and a politician runs for a seat. A similar logic applies in other European languages, including Czech and German, where a “chairperson” is the one who “sits in the front.”

Industrialisation brought chairs into our lives in large numbers. They finally became affordable—who hasn’t sat on a white plastic chair?—and gradually indispensable as work became more sedentary, a process that has continued with the digital transformation of the past decades.

Meanwhile, designers have made efforts to make seats more comfortable. The first office chair designed to respond to the sitter’s body and provide both support and comfort was the Vertebra in 1976, followed by the famed Ergon chair that same year. An array of ergonomic designs has been issued ever since. But these are often based on a standard body type and do not take into account the different needs of the people who will be sitting in them. Personalisation is one way around this. “Mass customisation is the buzzword we should have in mind here,” design theoretician Friedrich von Borries, a professor in Design Theory at the Hamburg University of Fine Art, says. “Just send a 3D scan of your body and get the perfect fit of your preferred chair—and why not, if you will use it for life?”

Regardless of whether it’s possible to design furniture to support our changing bodies throughout our lives, the comfort of a healthier posture comes with a price tag. Jess Percival, a digital marketer in the UK, has trouble placing her feet flat on the ground when sitting in most chairs. Since working from home, she has invested in an expensive, ergonomic office chair that suits her height, making her feel at ease throughout her working day. The switch highlighted the discomfort of the average seat: “Now if I have to sit on any other chair for long periods of time, I can’t stand it.”

We all seem to agree we spend too much time sitting uncomfortably, yet our culture offers few alternatives. We live in spaces designed around our chair-sitting habit, which informs other aspects of the built environment, such as the placement of windows or the height of tables. Mass-produced furniture can hardly reflect the diversity of human bodies, an experience familiar to both Griffiths and Percival, but also many people with an average frame.

“We either have to relearn existing modes of relaxing body positions, or redesign all the seats we know from trains, bus stations and waiting rooms,” von Borries explains. He notes that the first option would be more interesting, although the second one seems more realistic. Cranz argues we need to shift away from a compartmentalised way of thinking. A proponent of body-conscious design, she encourages both designers and users to take our bodies seriously, appreciate how they are put together and see them as dynamic systems.

So, should we squat at bus stops? Bounce on fitness balls during university lectures? Install standing desks in all offices and replace our sofas with a thick rug and an assortment of cushions? If it feels good, the answer is yes. Whilst we can’t expect our environment to change overnight, we can shake up our habits.