I’m driving past decrepit mines and massive wind turbines, from the Spanish coastal city of Valencia to an inland village called Oliete. Its name derives from the Latin for “olive”, and as I get closer, it is obvious why. Acres and acres of olive trees grow all around the area.

Their cultivation in the region was started by Phoenicians, continued by Romans, and ultimately improved with the technology of the Moors. In the following centuries, farmers built upon this foundation and continued to cultivate the small fruits. But due to former dictator Francisco Franco’s push towards industrialisation in the mid-20th century, Spain’s rural population started to decrease. A lack of labour forced farmers to abandon the ancient trees—most of which are between 100 and 1,000 years old.

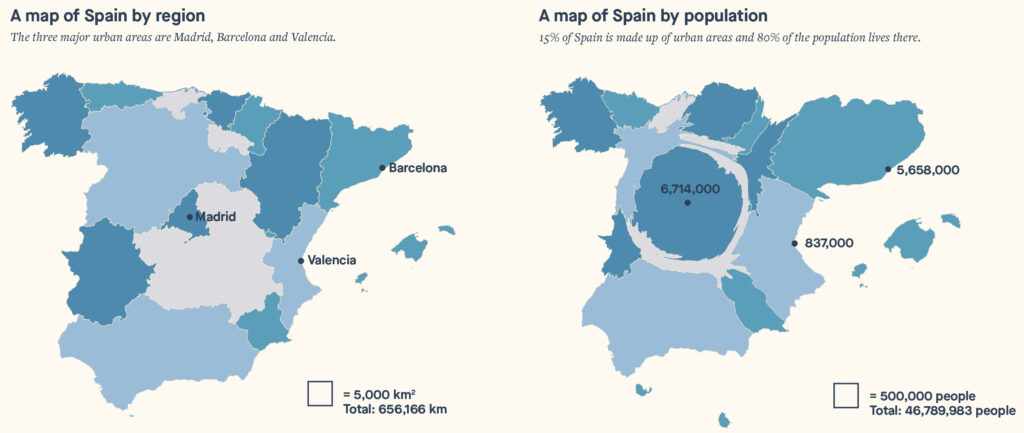

Throughout the last half-century, rural areas in Spain have lost around 30% of their population, as young people have moved to coastal cities like Barcelona and Valencia, or the capital, Madrid. The trend has left around 90% of the country’s population now living on only 30% of the land. They call the remaining 70% España Vacia, or “Empty Spain”. Thousands of pueblos (“villages”) across the country have been relegated to a quiet existence made up of empty summer homes, closed stores, and a declining population of elderly residents. They often wonder what will happen to the places they call home after they pass away.

Saving Oliete’s forgotten trees

I have travelled to Oliete, in Spain’s northeastern province of Teruel, to learn about an organisation called Apadrinaunolivo.org (“Sponsor an olive tree”). It is working to revive the area’s production of olive oil and simultaneously cultivating new life in the village. Started in 2014 with the goal of saving 100,000 “forgotten trees”, Apadrina offers people the ability to become a padrino (“godparent”) of an olive tree in the local area. After a donation of 50 euros per year, a godparent chooses a specific tree on Apadrina’s website. Their name is then added at the base of that exact tree, and each year, two bottles of extra virgin olive oil from Oliete appear on their doorstep. The more donations Apadrina gets, the more workers it can hire to care for a larger number of trees.

On a cloudy Sunday, I check into my room at one of the village’s two “rural homes” and head to El Rincón del Olivo, a cafe-store run by Apadrina. A friendly man sets down a green beer—made from olives, of course—in front of me and sits down to chat. Andrés Eloy Mujica is from Venezuela, and moved to Oliete in December 2020. He now serves the residents and tourists who walk through the cafe doors.

A few minutes later, the man I came here to meet walks in. His name is Jaime Grimaldo and he has one of those soft smiles that make you feel instantly welcome. In 2018, Jaime—who is also from Venezuela—was working on a PhD in depopulation and social innovation in northern Spain. He visited Apadrina and eventually decided to stay in Oliete. “The mountains here reminded me of my hometown in Venezuela,” Jaime says. He now manages the organisation’s donors.

Around 3,000 visitors per year come to Oliete, mainly to visit Apadrina. Before the organisation started, almost 100,000 trees in the area had been totally abandoned. So far, Apadrina has saved about 13,000 of them. As the organisation attracted more donors, its production capacity increased. More team members have been hired, which means new people are now walking the streets of Oliete.

Walking around the pueblo, we pass a group of children playing football on a hard-top pitch. “The school only had four students, but now it’s up to 13,” Jaime says. “Ten new jobs mean ten new families and new kids in the school.” He waves. “Three of them are Andrés’ children.” During my visit, people tell me that when a school closes, the pueblo itself will almost certainly die out, too. Because if there’s no school, raising a family in villages like Oliete becomes much more difficult.

Stargazing in Villar del Salz

“These days, the only time we see people is when there’s a funeral,” says Merche Urquiza. She’s sitting in the passenger seat as we drive past a humble procession in the tiny pueblo of Villar del Salz, just over 100 kilometres from Oliete.

The village was home to hundreds of full-time residents in its heyday, many of whom worked at a nearby iron mine. In 1987, the company, Sierra Menera, went bankrupt. Families in the area lost their livelihoods. Many left, and the surrounding towns and villages have never fully recovered.

Like many other Spanish villages in the region, Villar del Salz’s buildings are made with reddish-coloured stone. There’s a Catholic church in its centre. And the residents give off a neighbourliness that only comes from knowing almost everyone you see. Snow-tipped hills and industrial farmland provide the backdrop as Merche and her sister, Cristina, take me for a walk around the village. For them, it’s a special place, where they spend the summers surrounded by generations of family and friends. “Just so you know, the town is only a few streets,” Merche says in an attempt to tamper expectations.

Last year, Villar del Salz took on an additional sentimentality for the sisters when their grandmother, Cristina López Hernández, passed away at the age of 106. “She was the pueblo’s oldest resident,” Merche says proudly. Unlike the sisters, who grew up near Valencia and now live in Zaragoza, López Hernández was a lifelong woman of the countryside. She had worked on a farm from the age of eight, hosted soldiers during the Civil War, and had never seen the sea—only a two-hour train ride away—until she was 40 years old.

But those were different times: the lively days of rural life in the Spanish interior are long over. Villages like this one exist across the country and now face diminishing access to essential services, such as healthcare, basic internet connectivity, and banking. The grocer comes to Villar del Salz only a few times a week. The closest hospital is about 60 kilometres from here. “We’ve had people die in the ambulance on the way to the hospital because it’s so far away,” Merche says. Following the death of López Hernández and five other residents during the pandemic, Villar del Salz’s full-time population is now around 15.

Living in similar villages has become more difficult for the few who stay behind, and the likelihood of their regeneration has dropped as their population has continued to age. The Spanish government, the sisters say, has done nothing to help this process, so it’s in the hands of people like Merche and Cristina. Pondering the village’s future “keeps me up at night,” Merche says. In the year since her grandmother’s death, she has taken it upon herself to ensure that the pueblo does not also disappear. In the fall, she registered Villar del Salz into the National Host Village Network for Teleworking, an initiative started by online travel agency Booking.com and El Hueco—a Spanish social enterprise that works to facilitate long-term stays by remote workers in towns across the country.

Merche also built Villar del Salz’s official website to try and attract tourism to the area. It is full of information about hiking trails, places to stay, and the village’s newest attraction: a stargazing point, which we visit together that day. “My grandmother and I had this phrase we always said to one another: ’I love you to infinity and beyond,’” says Merche, who is an engineer, “so I built this lookout for her.” Sitting right outside the village’s front entrance, the stargazing point has now been certified by the Starlight Fundación—a designation granted to only five other lookouts in Spain. The label identifies the sky above that location as one of the best for stargazing.

Though they don’t live in Villar del Salz, the sisters go there several times a month, and stay longer during the summer. Given the lack of resources and services, it is not feasible for them to make a life in the village.

That’s why it’s vital, Merche says, to get the word out about the dying villages and remind people about the positive aspects of living in the countryside. If more people take an interest, the government will no longer be able to turn a blind eye, she explains. “My sister emails pretty much anyone about this,” Cristina tells me. After receiving a message from Merche, New York Times author Javier Sierra even visited the village. Perhaps tourists will follow. Merche hopes the homage to her grandmother will come to represent the cornerstone for a pueblo reborn.

Putting Teruel on the map

On my way to the city centre of Teruel, the hilltop capital of the province with the same name, I drive past a near-abandoned train station. Sipping a beer in a hotel cafe, I meet Amado Goded, co-founder of Teruel Existe (“Teruel Exists”). Its name alludes to a well-known Spanish joke about the city saying that it doesn’t, in fact, exist. The citizen movement, started in late 1999, works to promote the rights of rural areas and fight against depopulation.

Many others like Goded say that residents of non-coastal cities and towns across Spain have suffered not just governmental forgetfulness, but intentional negligence for decades. One of the group’s demands is financial inclusion in rural areas; there are 4,400 towns and villages without a bank branch, which makes banking difficult for elderly, less tech-savvy residents. They want the Spanish government to step in where private businesses don’t provide digital literacy training and ATMs in rural areas.

Transportation is another focus of Teruel Existe. To this day, Teruel is the only provincial capital in Spain without a direct connection to Madrid. Moreover, there is little to no public transport that runs between the towns and villages in the area. Aside from the lack of trains, a motorway that was supposed to pass through Teruel has yet to be finished. The group has recently called for the restarting of a bus line that passes through many rural areas from Madrid to Burgos. The Spanish government, they say, should use European funds for this and other networks to improve connection in the rural areas.

In 2019, Teruel Existe evolved into a parliamentary group after a nationwide movement by 20 provinces around Spain called for greater attention from the Spanish government. In 2021, it was registered as an official political party. Today, it has one representative in the Senate—the Spanish Parliament’s upper house—and two in the Congress of Deputies, the lower house. Goded tells me that Teruel Existe’s established presence inside the government will make it easier for them to keep their calls for action in lawmakers’ agendas. That’s important, especially for a group of people who are no strangers to being forgotten. Similar groups have joined the cause, including Aragon Existe and Soria ¡Ya!. Their work is vital to the provincial capitals, like Teruel, but even more so for the villages who face extinction if things don’t start to change.

Sparking the change

Back in Oliete, at the base of the hill, I walk up to Apadrina’s mill, where a black cat called Empeltre—after the black olive popular in the region—greets us. “He thinks he’s a dog,” Jaime says. The mill was built about six years ago and is where the olives are pressed into oil. From grinding the fruits to labelling the bottle, the entire process happens right here in Oliete. Moreover, the increase in demand for Apadrina oil allows the organisation to buy additional olives from local farmers, spreading the benefits of this system across the local community.

In the field, Jaime introduces me to his colleagues. Claudia is from Argentina, Manuel comes from a neighbouring village, and Juan Manuel—who goes by Coco—is an Oliete native. Germán is a Colombian who, after years of living in the United Kingdom, decided to move here to work with Apadrina. They’re on a short break from the latest task: pruning the trees. Each day they try to reach a different section of the large area they harvest from. We talk about life in the countryside; they seem to enjoy it. This team is a small but uplifting example of a pueblo’s regeneration in its early stages.

After we drive back to the mill, I go to the council-owned Piscinas Bar, one of the few cafe restaurants in the village, for dinner. There, I find a group of locals watching the Atlético Madrid match on TV. I take a seat at the bar and start to chat with the couple standing behind it: Maria Luz Soriano Lazaro and her husband, David García.

They spent years living in Barcelona, but began to rethink their situation amid the pandemic. “Our kids are grown up,” Maria explains, “and my mother was from Oliete. So we decided to apply to come run Piscinas.” Oliete’s council agreed. It’s been a major lifestyle change, but a good one. “It’s hard work. But you hear the birds singing in the morning, and my walk to work is on dirt, not concrete,” Maria says with a smile. Piscinas has an outdoor patio, full of chairs and tables waiting for people to fill them. Overall, it’s a pretty large restaurant; a third of Oliete’s about 350 full-time residents would probably fit inside. “In the summer,” David says, “the village is a different place.” Festivals and visits to parents and grandparents swell the population in the warmer months.

In Villar del Salz, Merche says the same: “You have to come back in the summer.” It’s then that the villages are once again brimming with life—family reuniting after time apart, bars open with visitors, and ice-cream-eating kids in bathing suits on a walk to the river. But when the rush is over and the winter clouds drift in, the reality of a village in decline becomes clear once again.

As I pull onto the road for the winding, three-hour drive back to Valencia, I think of the people I’ve met on this trip to Spain’s interior. Their connection to the land has given me hope. For these villages to turn around the decades-long trend, they’ll likely need people like Jaime and Merche to spark the change. But I wonder if this will be enough without the government stepping in to save them.

Along the two-lane track, the sun begins to set and I glance out the window at the olive trees on either side. As I leave their straggly branches behind me, I have the feeling I’ll be back one day. Will there still be someone to greet me?