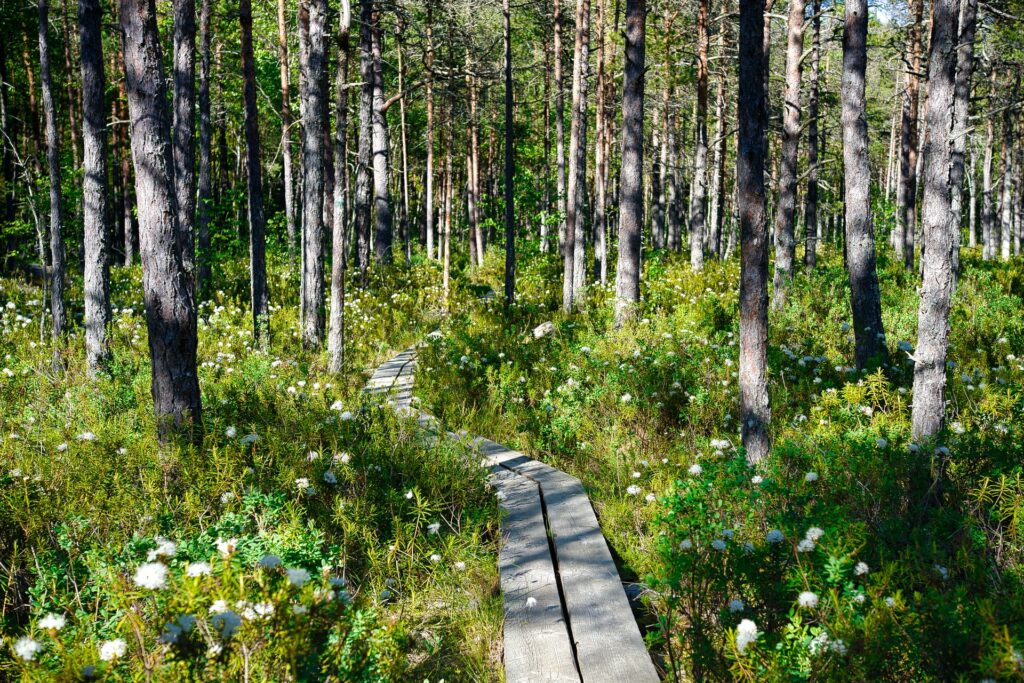

As we make our way through the forest, the hint of warmth from the April sun gives way to a cool, damp shade. Moss creeps up the slender trunks of tall trees—the mysterious world of the undergrowth releases its woody smells. Suddenly, we come to a clearing, dotted with stumps as far as the eye can see.

Mati Sepp is guiding us through Kaagvere, a forest outside the city of Tartu in Estonia, where clearings such as this are not a rare sight. The forestry and nature conservation expert is the founder of Eesti Metsa Abiks (EMA), an environmentalist group seeking to change Estonia’s forestry policy. The demand for timber—mostly destined to export—has caused an intensification of logging throughout Estonia, threatening the country’s biodiversity. As a result, entire areas of forest are being destroyed—with little regard for their ecological value.

According to Global Forest Watch, from 2002 to 2021, Estonia lost the equivalent of 20% of its tree cover. Continuous logging is causing a loss of 1% of forest per year. A factoid enthusiastically repeated by Estonia’s tourism board boasts that half of the country is covered by forest—but that number is contested. Only about 2% is old-growth forest, which boasts high levels of biodiversity and is ecologically more valuable. The rest is new—and less biodiverse—forest that was replanted to replace it, in some cases only to be cut down again.

In spite of European regulations for nature protection, the Estonian government continuously allows the logging of nature conservation areas. “Logging companies take down old trees and replace them with new ones. But old trees store more carbon than new ones,” Sepp explains. “This forest,” he says looking around at the clearing in Kaagvere with a frown, “was more than a century old. It will take more than 100 years for it to grow back and absorb the same amount of carbon dioxide from the air.”

Sepp used to own a logging business before becoming an environmental activist five years ago. He comes from a family of loggers and has witnessed a change in the culture of logging. “My father and grandfather, like me, used to work in the forest, but they were also forest protectors,” he recalls. “Now, I see that forest workers are no longer protectors.”

Sepp and his movement do not advocate against cutting altogether. Wood is needed for a number of things, from making furniture to generating energy. The Estonian timber industry is also one of the biggest employers in the country. But they are calling for Estonians to acknowledge that, unless something changes, there soon won’t be much forest left to chop down. “We won’t even be able to go hiking in the woods and enjoy nature, when being in nature is extremely important to Estonians and forms a large part of our identity,” he explains.

Forests are woven into people’s daily lives and heritage. Aside from having a place of pride in the country’s folklore and mythology, they provided a home, respite and shelter throughout a history of invasions and religious wars. The most recent example is Estonia’s Forest Brothers, a guerilla resistance movement that used an intricate system of bunkers and tunnels in the forest to fight against the Soviet invasion during the Second World War. Today, Estonians continue to seek out the forest as a place where they can connect with their roots, take a break and contemplate.

Deforestation threatens the loss of an important part of the country’s history and identity. But it is not just an Estonian problem. “Other European countries, such as Germany and Denmark, no longer have many forests. But we still do, and the rest of the world must support us in conserving them,” Sepp pleads. “Climate change is global and knows no borders.”