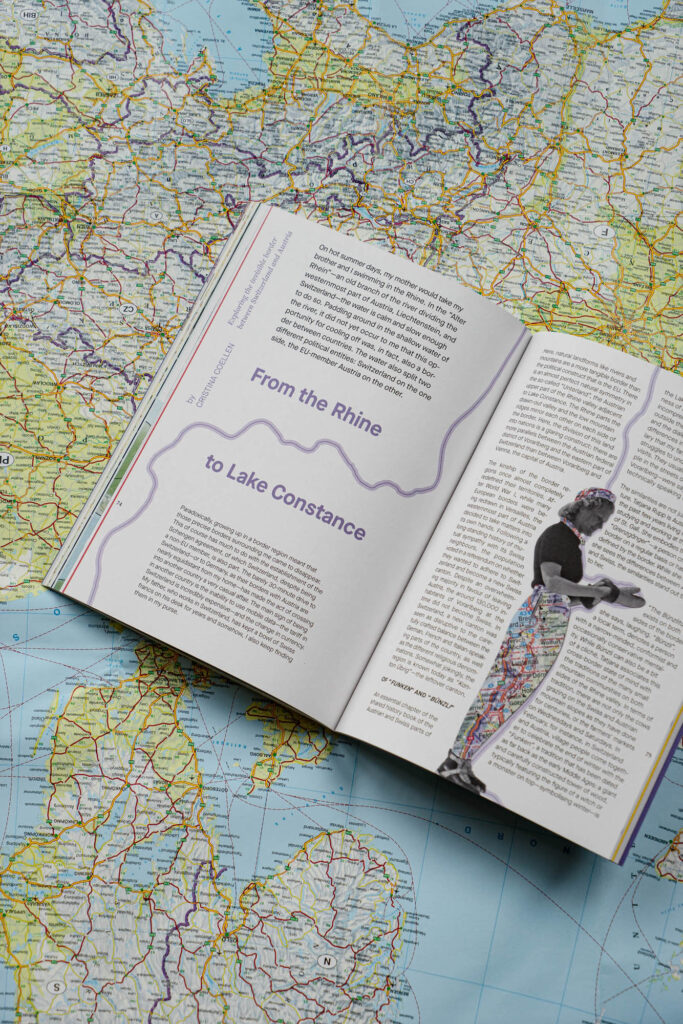

On hot summer days, my mother would take my brother and I swimming in the Rhine. In the “Alter Rhein”—an old branch of the river dividing the westernmost part of Austria, Liechtenstein, and Switzerland—the water is calm and slow enough to do so. Paddling around in the shallow water of the river, it did not yet occur to me that this opportunity for cooling off was, in fact, also a border between countries. The water also split two different political entities: Switzerland on the one side, the EU member Austria on the other.

Paradoxically, growing up in a border region meant that those precise borders surrounding me came to disappear. This of course has much to do with the establishment of the Schengen agreement, of which Switzerland, despite being a non-EU member, is also part. The barely 30-minute drive to Switzerland—or to Germany, as their borders with Austria are nearly equidistant from my home—has made the act of crossing into another country a very casual affair. The main sign of being in another country is the inability to use mobile data—as the tariff in Switzerland is incredibly expensive—and the change in currency. My father, who works in Switzerland, has kept a bowl of Swiss francs on his desk for years and somehow, I also keep finding them in my purse.

Here, natural landforms like rivers and mountains are a more tangible border than the political construct that is the EU. There is an almost perfect natural symmetry in the so-called “Unterland”, the Austrian upper part of the Rhine valley adjacent to Lake Constance. The Rhine parts the drawn-out valley and the low mountain ridges mirror each other on each side of the border. Here, the division of this land into nations is a glaring construct: there are more parallels between the Austrian federal district of Vorarlberg and the eastern part of Switzerland than between Vorarlberg and Vienna, the capital of Austria.

The kinship of the border regions once almost completely redefined their territories. After World War I, while many European borders were being redrawn in Versailles, the westernmost part of Austria decided to take matters into its own hands. Following a long-standing history of mutual sympathy with its Swiss neighbours, the population voted in a referendum on whether they wanted to adhere to Switzerland and become a new Swiss canton. Despite an overwhelming majority in favour of leaving Austria, the around 130,000 inhabitants of Vorarlberg at the time did not become Swiss. In Switzerland, a new canton was seen as disruptive to the carefully crafted balance between the German, French and Italian-speaking parts of the country, as well as the different religious denominations. Somewhat jokingly, the region is known today as “Kanton Übrig”—the leftover canton.

Of “Funken” and “Bünzli”

An essential chapter of the shared history book of the Austrian and Swiss parts of the Lake Constance region is the uniqueness of its dialects, which are practically incomprehensible to German speakers from outside the region. Both Swiss German and the dialect of Vorarlberg feature such differences in pronunciation and vocabulary that my family from northern Germany struggles to understand them during their visits. They usually have no idea what people in the streets of Bregenz—the capital of Vorarlberg—were saying to them, despite technically speaking the same language.

The similarities are not just of a linguistic nature. Tatjana Rupp is Austrian, but has spent the past few years living in Switzerland, studying and working at the University of St. Gall. She embodies the term “Grenzgänger”—a person crossing the border on a regular basis or having their life defined by the border. While she sees the differences between Austrians and Swiss, the similarities stand out the most to her.

“The Bünzlitum exists on both sides of the border,” she says, laughing. Bünzli, a local term, denotes a person with a narrow-minded, conformist and occasionally conservative mentality. While Bünzli can also be a bit of a cliché, Tatjana associates this cross-border state of mind with the traditions of the many small mountain communities on both sides of the Rhine valley. In terms of tradition, there are not only the cows grazing on the Swiss and Austrian mountain slopes as they have done for centuries, or the farmers’ markets on Wednesdays and Saturdays. In February, for instance, in Switzerland and Austria, village people come together to celebrate the end of winter with the Funken, a tradition that has been dated as far back as the early Middle Ages: a giant and carefully constructed tower of wood, typically featuring the figure of a witch or a monster on top—symbolising winter—is set ablaze. As everyone watches the tower—the Funken—burn down, there is music playing, children run around, and little stalls sell beer, sausages, and potato salad. It is one of the most important and unusual traditions of the region.

Nothing to declare

During the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic, the political border between Switzerland and Austria became awfully visible. Flights and trains were cancelled and border crossings abruptly closed. Around Lake Constance, fences were erected to mark a border that was imperceptible before. The situation only lasted until June 2020, but in those early days of the pandemic, months were akin to eternity. Newspaper front pages were plastered with pictures of the blocked border crossings, barricaded as if an army had to be stopped. For someone with the privilege of having been born in a part of Europe already united by the EU freedom of movement, they were unpleasant to look at, to say the least. I had only known a sense of natural shared space, rather than of division.

The impact of these sudden separations echoed through Vorarlberg, eastern Switzerland and the German states of Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria. The four regions rely on lively economic exchange amongst themselves and open borders have been crucial in contributing to the prosperity of the whole region. Commuting across national borders and exchange between the three countries are a defining characteristic of working life in the area; around 8,000 citizens of Vorarlberg work in Switzerland, for example, and a similar flow runs between Germany and Switzerland.

The border closures also severed personal relationships that had developed in this shared space. Families and couples living in the region are often Austro-Swiss, Austrians go to study in Switzerland, and Swiss cross the border to work in Austria. But if there is someone who knows about the weight of borders, it is my mother. Having grown up in eastern Austria during the Cold War, she lived right next to the Iron Curtain. To her, being able to cross a border in almost complete freedom was by no means natural. She recalls how, as a child, on a trip with her parents, she was standing on top of a hill in the Austrian region of Burgenland, from where one could look towards the Hungarian border: “Us children were then told: ‘If you go over there, they will shoot you’.”

She moved to Vorarlberg in 1990. Of the Swiss border, she says: “Even before Schengen, it was always a border of mutual respect. When crossing into Switzerland by car, there was the saying: ‘Fenschter runter und nünt dabi!’ meaning that you should roll the windows down and have nothing to declare.”

The border between Switzerland and Austria might have reopened again after the first wave of the pandemic; yet it is not easy to cross for everyone. In terms of immigration, the region is much less accessible to those from outside of the European Union. This is especially the case for Switzerland, where even citizens of the EU can have problems obtaining work and residence permits. As one of the most desirable locations for immigration, Switzerland has developed strict laws for non-EU and non-EEA citizens, selecting only skilled workers who are urgently needed and who cannot be replaced by Swiss citizens.

Crossing the border into the EU is admittedly easier. This is exemplified more specifically at the border itself—crossing into Switzerland by car, one needs to drive slowly past the border guards. On the Austrian side, the border posts are long closed, and in the twenty-something years of driving from Switzerland to Austria, not once have I seen a single soul controlling the traffic into Vorarlberg.

Looking out from my window over the valley of the Rhine and towards the Swiss mountains, watching the sun slowly sinking into Lake Constance, neither the Rhine nor any indication of the political border of the EU are visible. On this edge of the EU, in the quaint little villages of the Austrian and Swiss Alps, these borders will continue to play a rather banal role in the region and in the lives of its inhabitants. The same cannot be said of other EU borders. The multitude of news reports of refugees attempting to cross into Greece, Spain, or Italy—risking their lives in doing so—provide a drastic contrast to the peaceful border crossings between Austria and Switzerland. It is the invisibility of the border from the Rhine to Lake Constance between the two countries that fashions a particular privilege right at the heart of Europe.