My mother tells me that when our family arrived in the United States, I turned my seven-year-old back to the class each time the teacher gathered us in a circle. I would tear up the papers with their nonsensical writing and scribble over each assignment. The language made no sense to me, and my embarrassment showed through resentment.

Each time I’ve moved to a new country where I did not speak the language, I have fought the urge to let myself slip into that shame. Fashion has helped me express myself in lieu of words.

In Paris, I met Vincent Frederic Colombo. The fashion designer and artist founded his line C.R.E.O.L.E as a way to create the references he was lacking. “Ever since I was a kid, I rejected many things because I didn’t want to be placed in a box. I feel like it’s still my leitmotif,” Vincent says. Born on the archipelago of Guadeloupe, Vincent first grew frustrated with stereotyped Creole identities while looking at postcards of the Caribbean. He began designing clothes that pushed back, not to reach a new definition of Creole identity, but to challenge the need for a definition.

For Vincent, fashion design is a method of escape and resistance. “I think for many fashion designers, their work is a type of introspection. They explore an aesthetic they were exposed to as kids and try to recreate that perfect vision.”

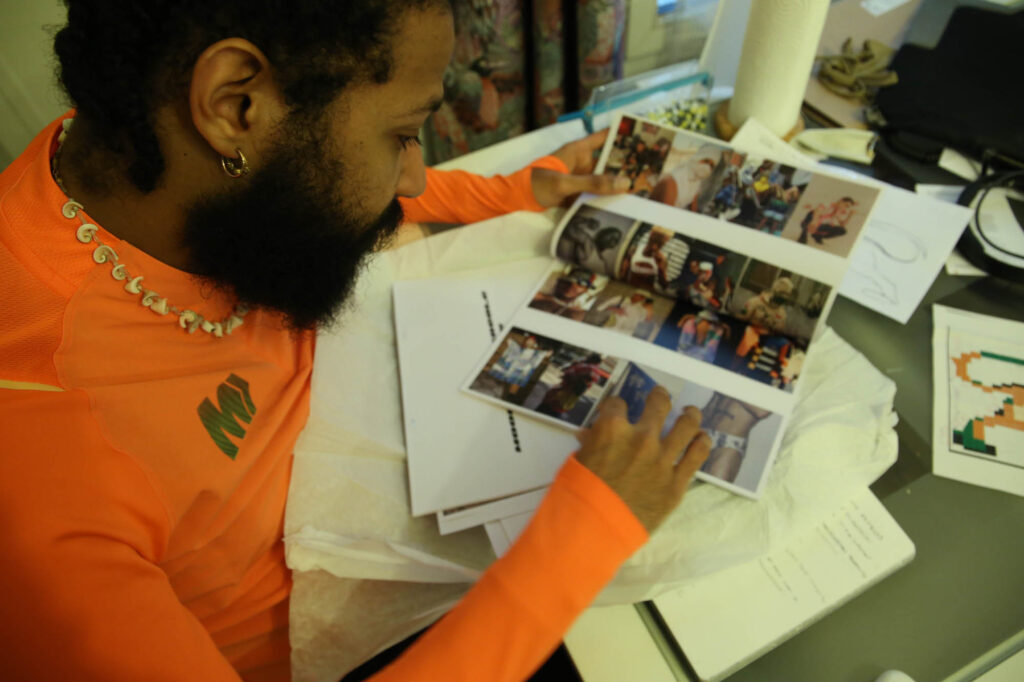

Seven different mood boards mark the starting point for Vincent’s designs: style, casting, techniques, graphics, hair and make-up, accessories, and graphic design. “The mood board is like my Bible. It is my basis.” Vincent uses them to test the ideas and messages he wants his clothes to convey.

An emerging theme for his new collection is the Lion of Judah, a reference to Rastafari culture. Vincent embroidered his own design of the image, using beads, onto a hoodie. “It’s interesting to work on the aesthetic and play with this fluidity, to create a dialogue with what’s supposed to be Rasta.”

Before studying fashion design, Vincent studied sociology and anthropology. For him, making clothes is as much an intellectual conversation as it is a creative exercise. Each reference, each detail, adds to the universe Vincent envisions. The hemline of the hoodie ends slightly above the waist to contest gendered affiliations, the use of tartan fabric confronts British colonialism, the threading exposes traces of the collarbone to infuse sexuality with workwear. The Lion bears witness to the symbol’s Judaeo-Christian and African heritage.

“We are not mood boards. We are not models. We are not trends. We are not a moment—we are a movement.” Quotes from activist-artist Alok V. Menon are scribbled throughout Vincent’s notebook. “People want the aesthetic of diversity, but they don’t actually want us.”

Also a DJ, vogue dancer, and party planner, Vincent takes these words to heart in his life and work. His music blends genres, his parties integrate communities, and his clothing brings together styles associated with clashing social identities. It resists being put in a box. Designing for fluidity is C.R.E.O.L.E’s ethos. It is about capturing movement and practising dialogue, challenging the notions of uniformity and agreement we have internalised, and that so many of us feel uncomfortable with.

While aiming to capture Vincent’s movements, the joy that lights up his face when he’s at work, I felt inspired. To resist that fear of exclusion, to confront the shame I learned. Through the clothes I wear, I express the intimate parts of myself—acknowledging even parts I did not know. They are a culmination of the music, friends, and circumstances which shape my actions and visions. I realise now that there is greater shame in not knowing your own language than that of others.