In 2019, a harness-clad Icelandic performance group named Hatari appeared on the Eurovision song contest stage to perform their song Hatrið Mun Sigra (Hatred Will Prevail). Through screaming, singing and strobe lights, the group shared their dystopian vision of the future: a society crippled, collapsed by consumerism, capitalism, and hate. The band achieved such popularity that Icelandic children began dressing up as members of Hatari for Halloween.

Hatari, or “hater” in English, describes itself as an “award-winning, anti-capitalist, BDSM-inspired performance art group.” The group is composed of Matthías Tryggvi Haraldsson, Klemens Hannigan, and Einar Stéfansson, who have clearly expressed their stance on the European Union. “The three of us are probably the most pro-EU people you will find in Iceland,” Haraldsson told the music magazine The Line of Best Fit. “Klemens is obviously raised with this idea of negotiating for the EU, his dad was working on it,” Haraldsson explains. “My dad was the chairman of the Icelandic pro-EU society: Icelanders For Entering. So we’re all raised with this Euro-positive attitude around the house.”

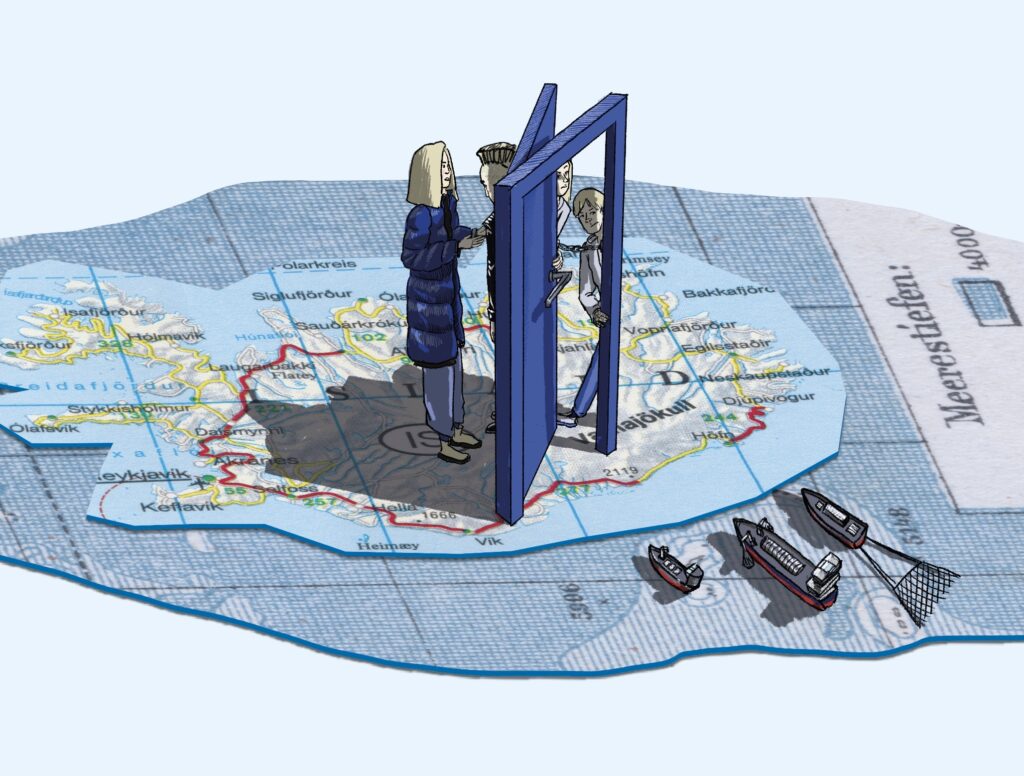

Since 2009, Icelanders have been in a sociopolitical limbo over whether or not to join the EU. The group’s growing following signals their message is received. Some of the band’s views are mirrored within the Icelandic population, but many young people describe feeling in the dark.

Whose waters?

Icelandic politicians—including, most recently, prime minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir—have largely said that the island country should not, and will not, join the Union. In an article published by Nouvelle Europe, Alyson Bailes, a former visiting professor at the University of Iceland in Reykjavik, argues that concrete issues—especially the sovereignty over its fishing quota system and agriculture production—were the main obstacles on the path of Iceland’s inclusion process.The European Commission signed agreements with coastal non-EU states like the UK and Norway to coordinate fishing activities. Joining the EU would mean adopting the Common Fisheries Policy, which determines which member states are allowed to fish for which types of fish and in what quantities. According to the policy, “Community fishing vessels shall have equal access to waters and resources in all Community waters.” In concrete terms, this means that other state members’ vessels could be allowed to fish in Icelandic waters. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in 2018 Iceland itself accounted for nearly 1.5% of global fisheries in volume.Even among young Icelanders, losing sovereignty over fishing is perceived as a serious threat.

“The thought of just letting all the European nations come and fish whenever they want to,” 22-year-old Diljá Sól Jörundsdóttir says, “that’s really something no Icelander is interested in.” “That’s what people don’t want to give up,” 23-year-old Tryggvi Kolviður agrees, calling EU mem- bership a “scary and dramatic change.”Óttar Ómarsson, 21, was born in Iceland, but works in Copenhagen, Denmark. According to him, this is a common feel- ing among Icelanders. Despite his strong attachment to the EU, Ómarsson shares the same fear that is voiced all over the island. Even though he says only rich families control the fishing industry, he thinks it is better that the fishing industry remains in Icelandic hands. “Still,” he says, “it’s ours, right?”

The crisis’ aftermath

Árni Þorlákur Guðnason, 42, is an Icelandic- born teacher currently living in Germany.

In his spare time, he coordinates an underground punk music festival that he co- founded in Iceland, called Norðanpaunk. “Many Icelanders,” Guðnason explains, “think we are better off managing our own resources than that bureaucratic monster in Brussels that nobody understands.”Iceland’s wealth developed after WorldWar II, when the introduction of engines for fishing boats led to the country’s economic take-off. Between the 1990s and the early 2000s, the country became one of the wealthiest with its GDP ranking 12th in the world and above most EU countries. The global financial crisis of 2008-2011 then caused the collapse of the Icelandic currency, with almost 5,000 Icelanders emigrating in 2009 alone. That’s 1.5% of the population.

The financial crisis bled into the political sphere. While the country’s three biggest private banks defaulted, Iceland’s potential integration process in the EU jump-started. The Social Democratic Alliance—under prime minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir—presented an application to join the EU in July 2009, hoping that the membership would have helped Iceland’s distressed economy.Popular support was only ever “marginal” according to Tim Gemer, former researcher at the College of Europe, due to both economical and identitarian concerns.In 2015, the new centre-right government requested that the European Commission no longer consider Iceland as a “candidate country”. Iceland’s foreign minister Gunnar Bragi Sveinsson declared that “Iceland’s interests are better served outside the European Union.”

The pride of being Icelanders

While dominated by tangible issues like fish and currency, the debate is ultimately shaped by identitarian reasons. “Iceland is an island in the middle of the ocean,” says Tryggvi Kolviður. “We’re more disconnected than most countries, and we’re happy outside of the EU.”Árni Þorlákur Guðnason disagrees. “That’s an island mentality,” he says, “to emphasise that you are independent and are stronger fighting on your own than being part of a coalition.” “Alone,” he argues, “each country is just a leaf in the wind.” He believes that a small island like Iceland cannot independently negotiate in the globalised world. “It’s a tradeoff between self-determination and cooperation,” Guðnason concludes.Despite their political and generational differences, Guðnason, Jörundsdóttir and Kolviður share the same concern: politicians are not exploring their country’s potential EU candidacy application in order to protect their own interests. The Federation of Icelandic Fishing Vessel Owners, along with 71.9% of the Icelanders working in agriculture or fisheries, is against EU membership.

Guðnason holds all political parties responsible for this silence. “We were tricked by political parties that had other agendas that appealed to voters,” he says. Despite promising that the population must decide on EU membership, he thinks that politicians have consistently kept the public out of this debate.Today, public opinion has shifted. While less than 30% of Icelanders were in support of joining the EU in 2016 and 2017, that number climbed to 47% in March 2022, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But most of all, young Icelanders want to know more about what membership means. Jörundsdóttir and Kolviður say they feel that there is no common understanding of what the membership process entails. The lack of information leaves them feeling—like many of their peers—frustrated.

The other side of the coin

The debate over Iceland’s entry into the EU seems to be closely linked to its entry into the Eurozone. Óttar Ómarsson believes that his country fully embraces all of the democratic pillars that other members have, and those were not part of the debate on EU membership. “The biggest question wasn’t to join the European Union for its values,” he says. “It was more like: are we going to take up the euro?”Even though the country was able to rapidly recover from past crises, the lack of diversification in the economic sector still makes the Icelandic krona susceptible to high variations in the exchange rate. Árni Guðnason is frustrated by the volatility of the local currency and believes that adopting the Euro could bring stability.

While recognising the reliability of the euro, Ómarsson emphasises the uniqueness of belonging to a country like Iceland. “We are really proud of being 300,000 inhabitants and having the Icelandic krona rather than a euro,” Ómarsson concludes.“We would like more information,” says Diljá Sól Jörundsdóttir. Jörundsdóttir knows that Denmark was able to maintain their own currency while entering the EU, but she has not found information explaining if this is possible for Iceland. According to the 22-year-old, “it would be helpful to have someone tell us in an easy language: this is what would happen if Iceland joins the EU.”Tryggvi Kolviður is pragmatic. According to him, the Icelanders’ sentiment toward EU membership fluctuates depending on the living conditions on the island. Joining the EU “would be a bigger discussion if we had a national crisis, but I don’t think the general public is concerned about not being in the EU as long as everything is going fine.”