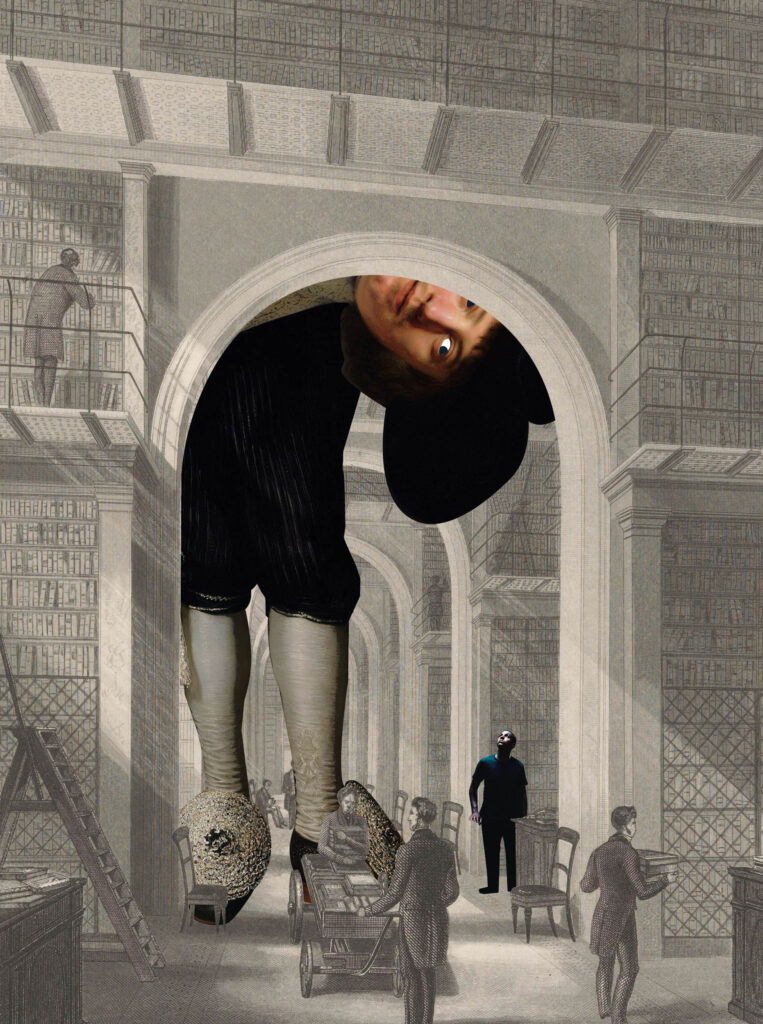

Studying postcolonialism at a higher academic level in the U.K. has its own set of ethical and moral trappings. Broadly, post colonial studies refers to the study of cultures and societies after they have gained independence from colonial rule, and includes migrant and diaspora studies. But the academic insti tutions teaching these subjects were built to the disadvantage of people of colour, much like the rest of society.

During British colonial rule, education was used as an instrument of the colonial project throughout the British Empire. Inter twined with the Church, missionary schools formed the basis of education, both abroad and at home. European conceptions of civilisation meant that colonised people were wrenched from their own cultural practices in favour of Western, Christian ones through sustained violence and subjugation.

Across the Empire, the education system set up and left by the British imposed a Western thought and belief system without any allowance made for those that they supplanted. These racist values are still be ing upheld today both in the U.K. and in its former colonies in its university reading lists, the English literary canon and in the scientists and inventors we are taught to celebrate. In such a system, it’s hardly surprising that Black students are less likely to succeed when the very foundations upon which it was built ensure their exclusion.

So what are the ethics, then, of engaging in post-colonial studies within such institutions? How can we begin to examine the effects of colonisation from within the confines of academic institutions built upon such foundations? Several nonprofits in the U.K. are finding an answer to these questions.

The Free Black University is a crowdfunded project that emerged in June 2020 and aims to provide a new form of knowledge production that centres the work, writings and teachings of Black academics and students outside of an academic institutional framework. Founder Melz Owusu said in an interview in The Guardian that they decided to launch it because “the world’s eyes are on how do we actually make Black lives matter, and one of the ways I think that will happen is through transformative education.” Through a podcast, lectures and distributing free copies of Black radical texts, the Free Black University offers people a parallel education, outside the formal knowledge production of academic institutions, focused on Black radical thought.

Other organisations, like U.K. charity The Black Curriculum, focus on reforming the current system to make it a more sustainable and supportive environment for Black students and aca demics while alternative educational frameworks are being built. According to their website, The Black Curriculum is a “social enterprise that aims to deliver Black British history all across the U.K.” by offering workshops and consultations with schools to modify their curriculums to include more Black history and literature.

Rhodes Must Fall is another organisation working to modify the British education sys tem to make it workable for Black people. Simphiwe Laura Stewart is a co-convenor at Rhodes Must Fall Oxford, a campaign that started at the University of Cape Town in South Africa to remove the campus statue of Cecil John Rhodes, a British colonial who expelled Black people in South Africa from their land for industrial development. After four years of pressure, Oriel College, part of Oxford University, has now agreed to remove the statue of Rhodes that stands outside it, but it will remain in place until at least 2021.

Stewart refers to higher education in the U.K. as “the academic industrial complex,” referring to the marketisation of the British higher education system, which systematically excludes Black students. She sees the work of the decolonial project of Rhodes Must Fall as conceptually concurrent with the work of the Free Black University. Where the latter is working to create something new, Rhodes Must Fall is working to reform the current system until society is at a point where initiatives like the Free Black University are the norm.

“Rhodes Must Fall is interested in decoloniality by first addressing some of the structural inequalities that are the result of the complicity of a university like Oxford in imperialism, colonialism and slavery,” she says. “If we think about the framework of decoloniality, its aim is consciousness raising, to the point that the academic industrial complex no longer exists.” Stewart stresses that while this is the end goal of Rhodes Must Fall, “our effort right now is centred on raising consciousness and making sure that the space that we have is one that’s more responsive to an indigenous, non-Western epistemic and ontological tradition.”

Alongside the efforts of organisations like The Black Curriculum, which works to diversify the curriculum at primary and secondary level, Rhodes Must Fall is doing essential work to force academic structures to adapt to become more inclusive and offer real equity in opportunities.

The education system, especially at university, sustains itself on a myth of meritocracy. When working in postcolonial studies academically, you can’t help but acknowledge your own social standing in relation to the text, history or artefact that you’re studying. If you’re going into this course as a white person, it’s important to be aware of the space that you occupy within the classroom and what has helped you get there.

Acknowledgement is never enough. White students of postcolonialism have to be prepared to back this up with words and actions: hold your institution to account if they aren’t signed up to the Race Equality Charter, an initiative from Advance HE that aims to improve the representation, progression and success of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic staff and students within higher education. Join outreach programmes and offer mentoring where you can. Listen when people of colour are speaking.

Studying non-white voices and cultures alone does not fix the systemic injustice. We need to put the theory into practice.