“When the project came up, I knew we had to take it,” says Professor Jo-Anne Bichard about Our Future Foyle. The urban intervention aims to redesign the river area in Derry, Northern Ireland. In the city with the highest suidice rate in the UK, the Foyle and its namesake bridge are notorious spots for people taking their own lives. The Northern Ireland Public Health Agency (PHA) commissioned a team of designers to revitalise the area, and prevent cases of suicide.

At one community workshop, Bichard and her team learned of a famous local story. In 1977, at the height of “The Troubles”— when the streets of Derry were marred by sectarian violence and division—a lost orca whale, fondly nicknamed “Dopey Dick,” was spotted swimming in the Foyle. The river is an emblem of the religious divide between Protestant unionists residing in the east bank and Catholic nationalists on the west. As locals gathered along the riverbank hoping to catch sight of Dopey, for a short while, communities on both sides of the river came together. This inspired Ralf Alwani, a designer and architecture researcher at the Royal College of Art, to create a space for research and engagement in the shape of a whale in 2016. “The response was amazing,” said Alwani, speaking to The Guardian in 2018. “We began to understand how Dopey Dick, coming at a time of conflict for the city, still resonates as a positive memory. So then we began to think about how the project could create what we hope will be a new, positive memory.”

But generating a sense of positivity around 73 something as serious and tragic as suicide is a difficult challenge. Mental health experts within the PHA advised Bichard not to talk about suicide directly. Their guidance suggested that highlighting an association between a place and self harm often leads to more attempts. Throughout the engagement process, it was nonetheless clear that locals were very aware of the problem.

“People would tell us the river had an association with suicide,” says Bichard. “The city has a saying, ‘I’m about ready for the Foyle,’ indicating periods of stress, highlighting how embedded the river is within the city’s well-being.”

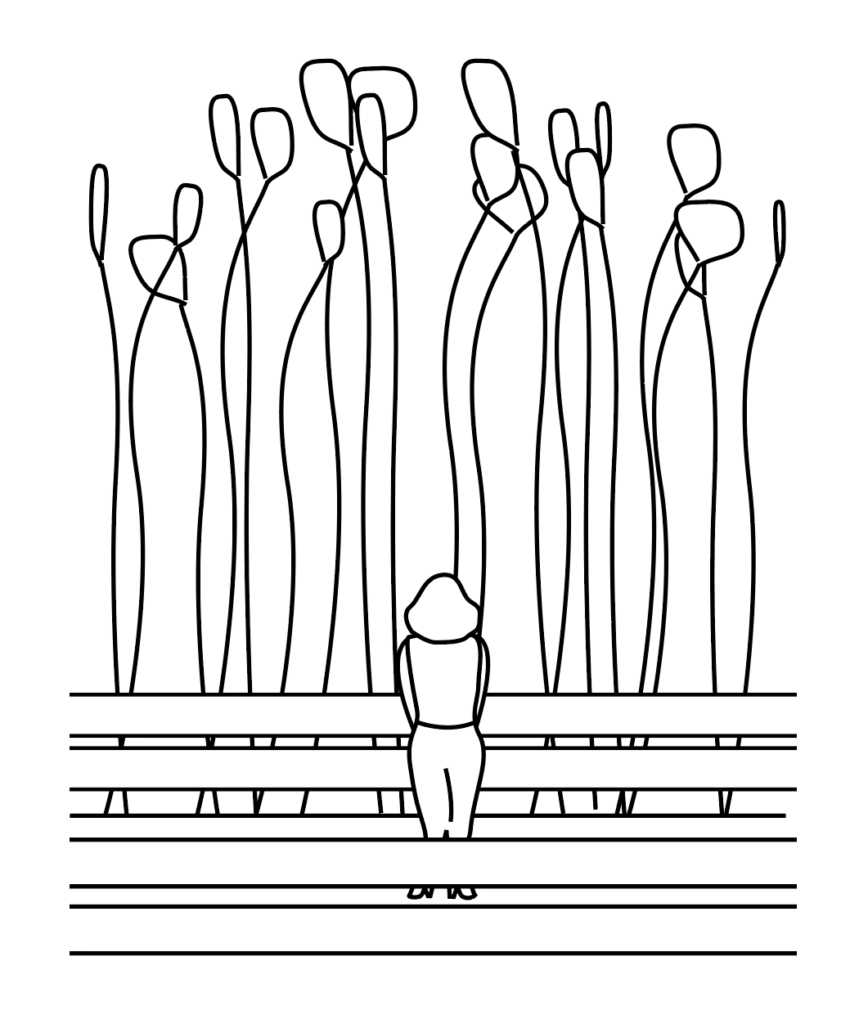

Alongside engagement with residents, the team also sourced their ideas from the natural world. “The landscape surrounding the Foyle Bridge is absolutely stunning,”says Bichard, recalling times spent walking and documenting along the riverbank. “We took some amazing photos of reed beds against a dramatic sky.” That was when they came up with a crucial idea. They would use the grace and beauty of the reeds to alter the atmosphere in and around the bridge, regenerating its soul and creating a connection to the nearby living world. At the same time, they would erect a seemingly unintentional barrier to prevent people from jumping.

“Derry was still emerging from the trauma of The Troubles and typical suicide prevention barriers were somewhat fortified,” admits Bichard. The design they produced, known as “Foyle Reeds,” is “an interactive arts piece that also just happens to tackle suicide behaviour rather than highlight it.” The artificial reeds will tangle and weave across the bridge at different heights, the tops swaying in the wind. Using digital technology, part of the reeds will be illuminated, changing colour as movement along the bridge is detected by sensors. Due to be completed in 2023, Foyle Reeds promises to become a landmark piece of design—a permanent and uplifting art installation and public safety measure, inspiring and protecting the citizens of Derry.

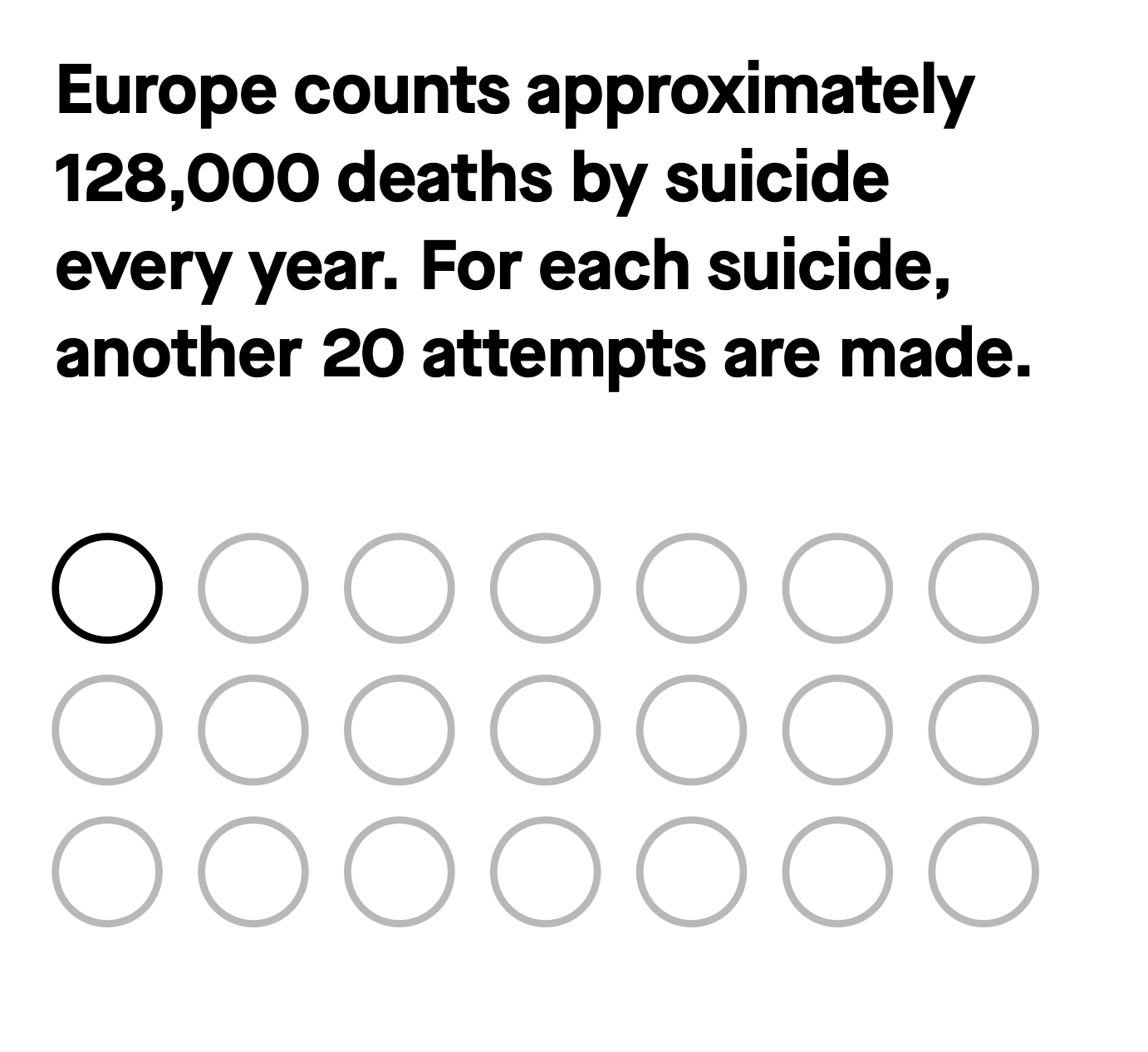

The issue of mental health is a serious concern for communities throughout Europe. According to the WHO, suicide is the cause of approximately 128,000 deaths in the continent each year, and for every person who takes their own life, a further 20 attempts to do so. It is a problem that particularly affects young people. Suicide is the leading cause of death amongst 10-19 year-olds in low-income European countries and the second leading cause of death in Europe’s wealthiest countries. Aside from medical services and helplines, design solutions can help alleviate this crisis. The UK based think tank, The Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health, provides research and ideas alongside reports from cities all over the world, highlighting the benefits of this approach. It believes building mental health into the design of our urban environments is the key to “a healthier, happier urban future.”

In Sweden, a recent study of youth suicide also emphasises the importance of urban design when considering space. Charlotta Thodelius, a researcher at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, wrote a paper about the way our built surroundings can affect health outcomes and the number of suicide cases among young people in Sweden’s cities. She believes that understanding the method and mindset of young people who take their own lives is essential to finding the best ways to improve urban spaces. “They are spontaneous and act very impulsively. They might not want to actually die, they just want something to stop,” says Thodelius, referencing studies of youth suicide in her country. “It might be something that has been going on for a while, but it can also be something that, as adults, we might find quite trivial—breaking up with a partner, fighting with parents, doing badly in a test, or being gossiped about.” According to the academic, it is often transitory moments of personal anguish, rather than underlying mental health issues, that elicit tragic, extreme responses.

This impulsive tendency amongst young people makes buildings such as high-rise towers and bridges, especially in depressed or isolated urban spaces, hotspots for suicide. Theodelius argues that if similar structures could be redesigned to avoid the type of spontaneous action young people might take in times of crisis, the number of suicide cases would significantly drop. “There are good reasons to modify the built environment around known hotspots and try to avoid creating new ones in city development,” says Thodelius. “This requires input from engineers, city planners and architects.” But crucially, Theodelius points out, these modifications must be carried out sensitively, with thought given to the mood of the surrounding space. “A bad example would be a bridge with unattractive suicide nets. This can easily stigmatise a place, and make the general public avoid it. A better example is a bridge with a fence covered in plants and flowers. This doesn’t affect a place in the same way—instead of being perceived as a suicide prevention measure, it can be seen as something to simply make the place nicer.” This approach reflects that of Bichard and her team in Derry. It attaches importance to the mood and feeling an area elicits rather than just focusing on the physical structures within it. As cities and towns expand or modernise, the built space must be designed beyond practical solutions, to alleviate negative feelings.

“As a species, we are still not too well-adapted to living in urban, built-up environments,” says Agnieszka Guizzo, a landscape architect who grew up in Warsaw, Poland. She remembers the long, dark winters of her childhood and the impact they had on her mood. Whilst studying in Porto, Portugal, she became fascinated by the relationship between the brain and our lived environment. She eventually co-founded NeuroLandscape—a team of researchers and professionals from across Europe who aim to help improve the mental well-being of citizens residing in urban landscapes. They organise community projects based on the latest neurological research linking urban design and mental health. Guizzo believes that growing urbanisation across the world can have a negative impact on our well-being. Our evolved unfamiliarity with urban structures is, according to her, “likely the reason why living in cities is associated with much higher risk of mental illness such as depression and anxiety than living outside of cities.”

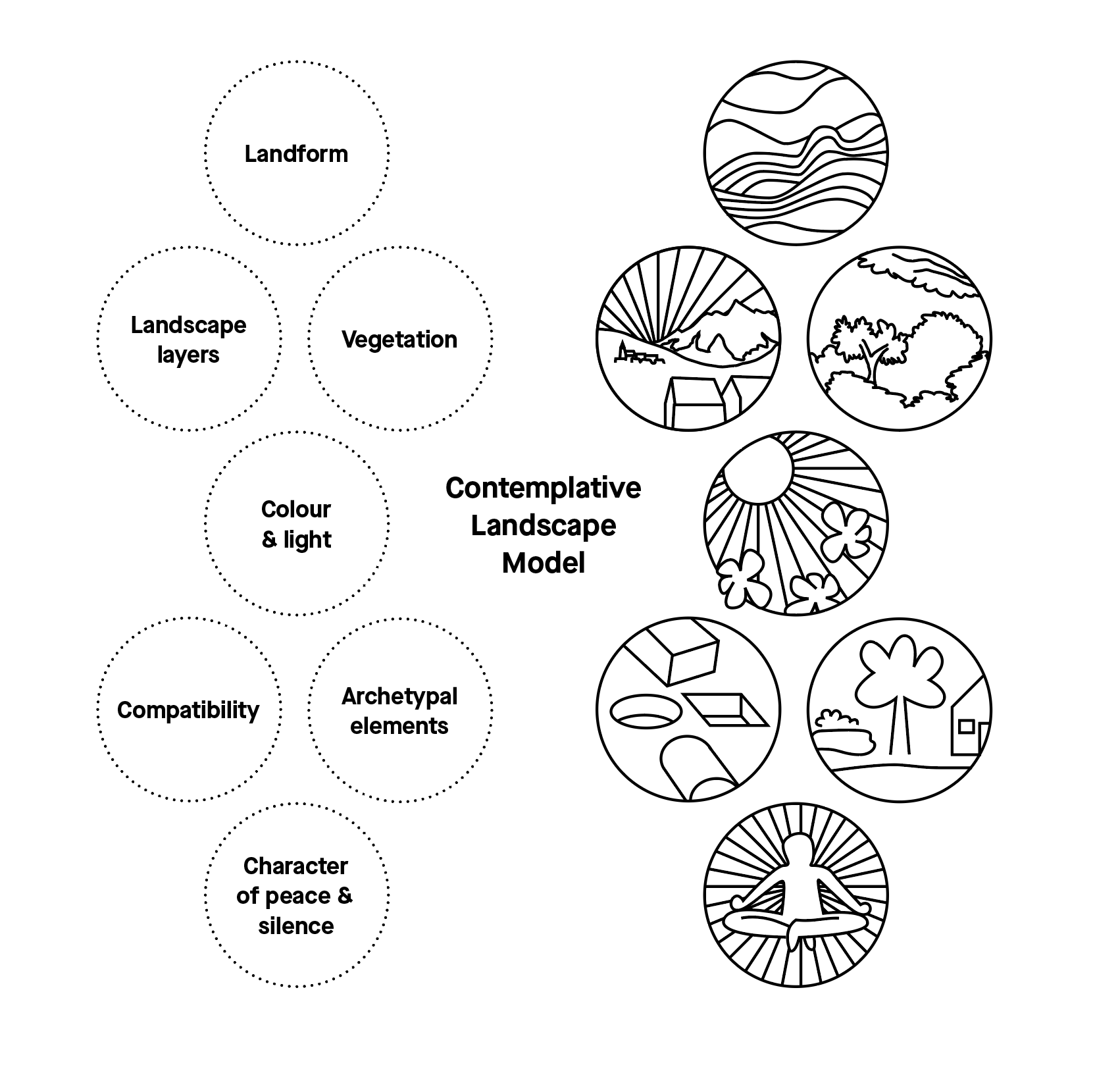

Her team has created a “Contemplative Landscape Model,” which measures and defines landscape aesthetics. The model consists of seven categories—including landform, vegetation, colour and light, character, layers of landscape—and can assess any landscape in terms of its “contemplative” qualities. “Some specific features present in the green space seem to ‘work’ better for our health than others. Surprisingly not all of them are related to plants and trees, but also other things like, for example, far-away views,” says Guizzo. To score highly, a landscape requires qualities such as an undulating landform with natural lines and broken or warm colours that allow light and shade to be visible, as well as seasonal, changing vegetation and a clear compatibility between the natural and created surroundings. Guizzo’s company even provides a service that allows organisations or individuals to complete a survey which gives a landscape, such as parks or institutional settings, a contemplative score. “I would advise planners and designers to incorporate as much natural asymmetry as possible in their designs,” says Guizzo. “It makes a lot of sense when you consider the evolution of our nervous system. Euclidean geometry—which posits that symmetry and straight lines occur naturally, ed.—is artificial and relatively new, while natural geometry expressed by fractals, for example, is more familiar to our brains.” Guizzo’s own research shows how brain activity alters when we are exposed to different window views. When high up, looking out at a wide, green landscape that would score highly in the Contemplative Landscape Model, brain patterns associated with positive emotional states appear to be more common than when looking out a window on lower-level floors, with less of a view.

Back in Derry, Bichard is hoping the familiarity and natural geometry of the Foyle Reeds will have the desired mood-altering effect and bring calm and beauty to the river area and its people. Perhaps the Future Foyle project will be the first of many public health and design initiatives across Europe. If this is the case, Bichard warns, it will be important to protect the environment and reflect the unique qualities of every community through local engagement. “We are in a really interesting but urgent time,” says Bichard. “We have a major mental health problem, especially amongst young people, but we also have a climate crisis to consider—solutions can’t come encased in plastic.” The Foyle Reeds are a permanent structure made from aluminium, a highly sustainable material. The 800-metre illuminated, sculptural barrier considers both people and the planet.

Today, more than ever—thanks to a deeper understanding of the effect of our surroundings on our mental health—there is an opportunity to employ design as a means to enhance our lives and even save lives. “I think that we have enough evidence to start designing in a way to cause less harm 77 to people,” says Guizzo. “For many years, cities were designed without consideration to human health, or if any, it was limited to sanitary matters. I believe that soon there will be a re-evaluation of priorities by our urban managers and there will be more health-promoting interventions.” With the unveiling of Future Foyle, this re-evaluation has already begun.