“We had French nationality, but not French citizenship. We were part of Europe, but we were not European. We were immigrants, but not foreigners.” Sitting in a Parisian café, my great-uncle reminisces about when he and his brother answered France’s call for cheap manual labour in the 1950s.

“What were you then?” I ask.

“Nothing. We were nothing,” he responds. “We were only allowed to come to France as guests, to work. That’s what we were supposed to do, work and then go back.”

Today, European borders are deemed immovable walls, the result of natural barriers clearly cut out in the form of a continent—ones that take the shape of migrant restrictions and a separation between an us and a them.

Yet, Europe once stretched into Algeria.

A French Algeria

In 1830, the failing French Bourbon monarchy set its sights on Algeria to reinvigorate the empire’s prestige and military might after revolts against Charles X. What was supposed to be a quick military operation—intended to turn people’s attention away from internal struggles and improve electoral support—ended in 30 years of genocidal carnage that wiped out one-third of the entire Algerian population. At the end, France claimed the nation as an extension of itself. For over a century after that, French people settled in large numbers in their new “French department”. By 1900, French settlers made up one-quarter of the population. Yet those native to Algeria were demoted to the status of second class non-citizens and lived under a Code de l’Indigénat (Indigenous Code) which restricted their rights to work, move, own livestock or property. They were also forced to pay arbitrary taxes which assured their inferior legal and political status.

When the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC) planted the seed of the European Union in 1957, Algeria was still a part of France. As one of the six founding members signing the treaty of Rome, France demanded the inclusion of its Algerian territory. To French officials, France was Algeria, and Algeria was France. It was only natural that Algeria was thus European. In 1957, Algeria was incorporated into the EEC as a symbolic “seventh member”.

But there was nothing natural about the drawing of the EEC’s initial borders. The inclusion of Algeria was a ploy to consolidate colonial power. At the time of negotiations, France was knee-deep in the Algerian War of Independence, 1954-1962, led by the National Liberation Front (FLN). The Algerian nationalist movement wished to reinstate the Mediterranean Sea as France’s outermost southern border. In the first months of 1957, the war reached its peak with a bloody campaign of urban guerrilla warfare against the French Algerian authorities—the Battle of Algiers. By late March 1957, the authorities had mostly crushed the FLN within Algiers. Its leadership had been arrested, tortured,and sometimes executed. Signing the treaty of Rome that same month was France’s last bid to hold its empire together.

After Algeria claimed its independence in 1962, the president of the newly formed Algerian state, Ben Bella, attempted to keep its ties with Europe. But most of his demands for migration rights and much-needed reconstruction funds were swept aside by the EEC, claiming Algeria’s independence as reason enough to ignore them. Then Minister of Foreign Affairs Bouteflika pushed for the recognition of Algeria’s place in the EEC—as agreed in the treaty of Rome—but the independent nation’s legitimacy remained blurry. Algeria’s membership of the EEC ended in 1976 with a newly negotiated relationship that ignored its past membership and considered Algeria simply a neighbouring country like many others.

An Algerian France

While the borders of Europe included Algeria when it was convenient, the conception of a closed-border Europe now excludes Algerian presence from its identity and history. The collective French memory has been remodelled to think of Algeria as a separate entity—a past colony. Yet, legally, it was never a colony. Algeria was considered a French department, forcefully attached despite the sea separating the two lands. As French historian Pierre Nora explains, “Algerians and Algeria came to be perceived as non-lieux de mémoire (non-sites of memory) or even lieux d’oubli (forgotten sites).” The European mark France has left on Algeria after 132 years of colonial presence is undeniable. But so is Algeria’s mark on France, for settler colonialism is not a one-way street.

Algerians are one of France’s largest post-colonial immigrant minorities, a presence that dates back more than a century. Algerian immigration was initially labour migration, due to the population decrease of World War I and the call for north African soldiers. In the 1920s, one-fifth of Algerian youth physically able to work immigrated to France. After World War II, travailleurs invités (guest workers) were called to fill in the growing need for cheap manual labour and rebuild a country ravaged by war. Initially, 700,000 Algerian men were legally allowed in. But the status of a guest worker, whose wages were lower than the law was supposed to allow, was temporary. After contributing to France’s manufacturing growth, the men were meant to return to Algeria. Many of them never did.

After the 1970s, a pattern of permanent family settlement began to emerge among north Africans living in France. Today, Algerian communities are scattered across the country, but they cluster in two cities: the southern cosmopolitan city of Marseille and the northern capital city of Paris. Though seen as the most quintessential French city, Paris holds urban pockets people colloquially call “Little north Africa”. They form what historian Pascal Blanchard calls le Paris Arabe, (the Arab Paris). Here, the word “Arab” has become a blanket term that denies ethnic diversity by capturing any and all French-north Africans into a net strewn with colonial prejudice, stereotypes, slurs, exclusion, violence, and criminalisation.

One of the most famous sites of Arab Paris is Barbès, a northern Parisian neighbourhood in the 18th arrondissement (district). Barbès is filled with north African shops, restaurants, butcheries, pastry shops, and fashion stores. One of the most iconic and famous ones is Tati, a north African landmark whose bright pink and blue sign hovers above a Haussmann-style building. Tati, which went out of business in 2021, was a discount department store built by Tunisian immigrants in the 1940s. It was a memorable—and hectic—place for many immigrant families who had found in Tati the north African souks (markets) of their childhoods.

Undeniably, Algerians who settled in Barbès in the mid-20th century have left their mark on the French landscape. Here, the verb “to settle” loses its colonial brutality to reclaim a softer nature. Algerians have settled in Barbès like a leaf settles on the ground, like a shell settles on the sand—organically—after decades of enticed immigration.

My maternal grandfather was one of these guest workers who immigrated to Paris in the 1950s with the idea of returning home—an intention that withered into an improbability. As a tailor’s apprentice, he left the Algerian countryside around Constantine—an eastern city nestled atop mountain ravines—to work in a Barbès couture atelier in need of cheap labour. A few years later, his brother joined him to open a little tailor shop in the middle of the immigrant neighbourhood.

“I made hundreds of Algerian flags that night.

I sewed and sewed until my machine broke.”

Erased from history

When I visit my great-uncle, his broken memory tries to stitch back together what he calls “his little Algeria”. He recounts the names of Parisian places where he finds bits of his natal home. The Place de Clichy where he lived, the neighbourhoods of Abbès and Anvers where his favourite Algerian cafés were, and Nanterre—where tens of thousands of north Africans first lived in shanty towns built to house them in a hurry.

“36 rue Goutte D’or, that’s where your grandfather opened the tailor shop,” he says, eyes lost in a time long past.

“What was it called?” I ask.

His eyes narrow in confusion. “It didn’t have a name. It was a measly thing. Why should we have named it? Just one room, enough space to put two sewing machines and a chair. There were scraps of tissue everywhere. And buttons, and needles. Wool, sometimes. I remember that.”

Many of these nameless tailor ateliers were later repurchased by the French state and offered to fashion designers at a discounted rent in an effort to develop the neighbourhood of La Goutte D’or. Today, there are no visible traces of Algerian grandfathers in the story of Paris’s fashion legacy.

Sifting through memories, my great-uncle turns his attention to another urban site of Algerian presence, Nanterre. In the 1950s, the state hastily built cheap wooden cabins in this commune to house a growing number of north African immigrants coming to work in Parisian factories. He remembers the shanty town in the western banlieue (suburb) as a muddy, foul-smelling amassment of 10,000 north Africans—mostly Algerians—living in leaking, poorly insulated shacks. Yet—his eyebrows rising up—he also remembers the coffee stands mimicking the cafés in Algeria and the men, sitting on wooden stools, playing games of dominoes or ronda like at home.

Since my grandfather’s arrival, the Nanterre shanty towns have been razed to the ground, replaced by their vertical doppelganger—cheap, high-rise social housing. Today, this type of public housing is found throughout Paris’ economically disadvantaged banlieues, and is mostly home to people of immigrant origins. Nanterre has been so thoroughly cleansed of its slums that it is almost impossible to retrace the history of the thousands of north Africans who lived here.

Many immigrants and their descendants now live among the ruins of a violent colonial union, erased from French society and culture. Today, France’s settlement into Algeria—a period that lasted for almost a century and a half—is considered taboo, barely mentioned in school programs or in public discourse.

After having spent my entire higher education studying French history, the first time I had heard about the 17 October 1961 massacre in Paris was through my grandfather. On that October night, the FLN mobilised the immigrant population to protest a curfew targeting Algerians living in Paris. What started as a peace march ended up a bloodbath when police officers opened fire on the crowd. Hundreds of Algerian bodies, dead and alive, were then thrown into the river Seine. It was not a covert operation done at the fringes of the city—this happened right in the heart of Paris, at the Pont Saint Michel next to the Notre-Dame Cathedral. That night, tens of thousands Algerians were arrested, many of whom disappeared.

“I saw two of my friends go to the march,” my grandfather told me. “No one heard from them after that. To this day, I don’t know what happened to them.”

It was in his measly couture atelier that my grandfather spent the night of 17 October.

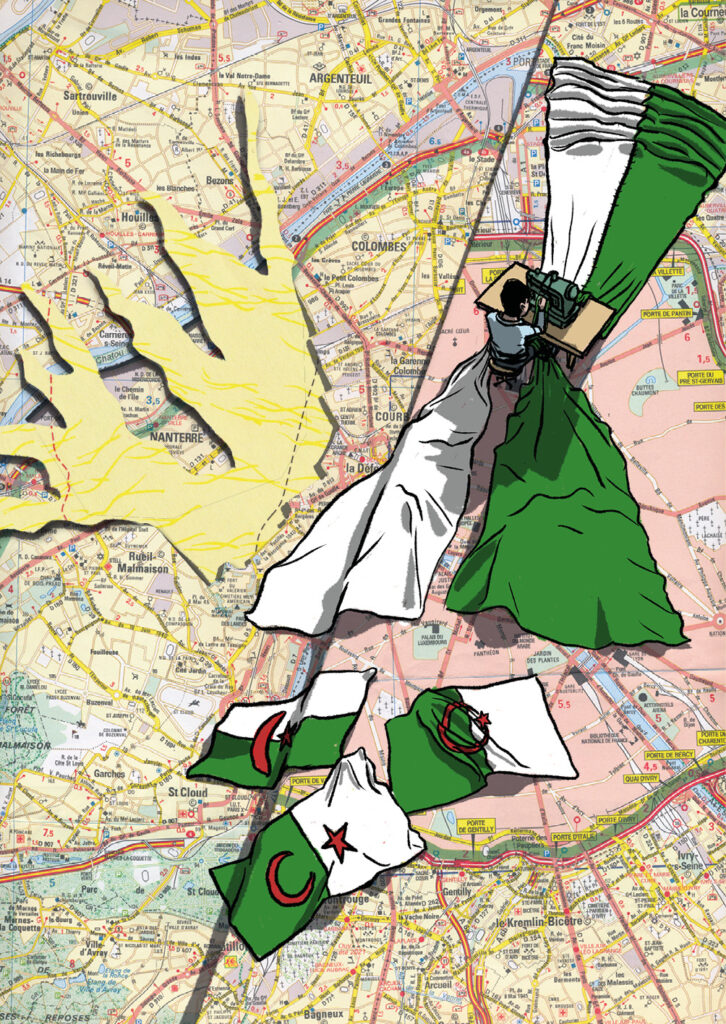

“I made hundreds of Algerian flags that night, for people to take to the march. I sewed and sewed until my machine broke.”

Later that day, French police arrested him. He spent weeks in prison for making the Algerian flags, which were outlawed at the time.

“Say you’re French”

As French president Emmanuel Macron stated in his October 2020 speech against “separatism”, France is “not the sum of multiple communities but one single community.” This is the very idea upon which French society is built—to be considered French, immigrants and descendants of immigrants are asked to shed their cultural and religious heritage. France’s view on integration borders on assimilation: an extreme form of inclusion that forces one to give up their culture of origin in order to completely blend into French society.

Growing up, I’ve seen my mother twist her entire being to reconcile her Muslim identity and her career in public education, where she was not allowed to wear a hijab. She could not practise her religion anywhere that was not at home and had to live through officials debating whether or not she could have pork-free options at lunch or shelves of halal meat in stores. She was expected to cut ties with her country of origin to remain neutral. In order to be considered truly French, these are among the many things that are expected of citizens of north African heritage.

“Keep quiet,” my grandmother always tells me. “Don’t talk too much about your Algerian heritage, say you’re French.”

French assimilation started during colonial times, when Algerians were called “French Muslims” and constantly held up to the standards of European settlers. To be granted French citizenship, they were asked to give up “Islamic law” and adhere to a “French Islam,” which forced Imams to sign a charter of rules to abide by. As subjects of the French empire, “French Muslims” were granted visas to work in mainland France, but it stopped there—they were never legally French, almost never allowed French nationality and the rights that came with it.

This ambivalent identity and legal status continued when Algerian men of my grandfather’s generation first arrived in Paris where they were called “French workers of Algerian origin”. The borders these men managed to cross turned out to be thin blades that sought to cut the threads of their Algerian identity. They were expected to come out barren on the other side, virgin slates on which they were asked to retrace the formal outlines of their beings in the hexagonal shape of France.

Through this erasure, France has turned my grandfather into a ghost, failing to recognise that a ghost’s purpose is to haunt the home that has been ripped away from them. Between Barbès and Place de Clichy, my jedo’s (grandpa) ghost scurries the Parisian streets he has helped garnish and shape, forever the pariah of a culture that erases his involvement.

Today, France has fallen into the clutches of a rising far-right party that has gained popularity by painting the portrait of children of immigrants refusing to “integrate”, and as scapegoats responsible for any and every criminal or economic distress. Politicians like Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour claim that the north African heritage of millions of French citizens should come second, or better yet, be kept in the shadows.

Bridging France and Algeria

As much as France’s physical and cultural borders have tried to sever the tie between French-north Africans and their countries of origin, they have failed. Today, many children of north African immigrants consider themselves both French and Maghrébins (Moroccan, Algerian, or Tunisian). It was a collective experience shared by the north African diaspora which helped strengthen those ties, one we call l’été au bled (summer in the homeland).

As dual citizens—most of the time—many children of north African immigrants have spent their formative summers in their ancestral lands. Every year, the school break marked the return to the homeland and the only time our parents could visit their family back home. For two months, many families lived in Algeria as if they had never left—not as tourists but as residents, reuniting with cousins and grandparents.

In these moments of union, stories of European Algeria and Algerian France were finally passed down to me. They are stories my grandmother still has a hard time sharing, stories my grandfather has taken to his grave. Summers spent in the homeland were a way for me to fill in the gaps of a French history that had forgotten Algeria and my family. But most importantly, these trips were what made me realise that the hyphen in “French-Algerian” was not a border but a thread, one that stitched the two identities together so tightly that it created one single entity.