For a small nation, Denmark has quite a global offering of late-night snacks. Around 2am, when the Danes in Copenhagen stream out of humid bars, some opt for the iconic hot dog, some hit up the kebab joint, and others head to the wide selection of colorful neon stands offering Chinese fast food – or, rather, Westernized Chinese food: chow mein, orange chicken, and fried rice, doled out in generous portions.

The more I looked, the more I saw the multitude of Chinese takeaways tucked into the street-level buildings of Copenhagen’s busiest quarters. As one of the only food options available in the wee hours of the night, Chinese food is a staple of the Danish snack-bar scene, but strangely out of proportion for a country with one of the smallest Chinese communities in Europe. In 2017, there were only 2,271 first-generation Danish citizens of Chinese ancestry and 11,000 immigrants from China.

No doubt ethnic food is an easy and fun introduction to new cultures. However, eating at a Chinese or Turkish or Thai restaurant is often removed from the political realities that marginalized minorities often face as immigrants. The exploration stops when the bill is paid.

And since many Danes’ only experience of Chinese food is likely to be this deep-fried, late-night fare, I wonder — as personal as food and the act of eating is, if the perception of Chinese food is cheap and of low-quality, how are the Chinese and Chinese-Danes perceived in Denmark?

Ethnic Food and Economics: The Danish Context

To better understand the history of Chinese restaurants in Copenhagen, I asked Chinese diaspora expert, Mette Thunø, Associate Professor at the School of Culture and Society at the University of Aarhus. Thunø explained that the earliest wave of Chinese immigration to Denmark was directly tied to the flourishing ethnic food industry pioneered by the first Chinese in Copenhagen in the 1950s: “With no obvious economic openings, skills, capital, or knowledge of the Danish language, the early Chinese in Copenhagen used the only resource available to them: their exotic appearance.”

By the mid-1960s, Chinese food was firmly established in Denmark – in Copenhagen and in smaller cities. During this period, the economic achievements of the Chinese-Danes in the ethnic food industry were amazing. The five largest Chinese restaurants in Copenhagen often had lines out the door. Danes were eager to try this new cuisine while seated in traditional Chinese teahouse settings, complete with red lanterns and lacquered windows. Recognizing opportunity, entire families began migrating to Denmark from China, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong to become part of this booming market for Chinese cuisine.

However, by the 1980’s, the Chinese catering business reached its saturation point. As the ethnic food market became overcrowded with newcomers and immigration from Turkey, the restaurants were forced to lower their prices and quality to remain competitive. Tasteful teahouses were quickly replaced by harsh fluorescent lights and plastic counters. Over time, the large restaurants disappeared and gave way to smaller counters that new immigrants could afford to set up. Today, the Danish term Kina grill refers to the sort of food outlet that sells hamburgers along with chop suey dishes.

Food and Integration

It is understandable to simplify a culture if our exposure to it is one-dimensional. Unlike the densely concentrated Chinatowns in cities like London, Paris, and Berlin, Copenhagen’s Chinese community leaves no visible mark except for the Chinese takeaway counters dotted throughout the city. Indeed, as Thunø writes, “In Danish eyes, [the Chinese in Denmark] exist only in relation to food; they are invisible as an immigrant community.”

Furthermore, although the first Chinese restaurants in Copenhagen were of higher quality than the current Kina grills, they were still Chinese caricatures. They presented a sanitized version of Chinese cuisine and culture, with servers dressed up in outfits no one in China has worn for over a century. If the only exposure a society has to another culture is through its cuisine, the quality of which has always been either simplistic or low, it’s understandable, though painfully flawed, to assume that the culture’s economy and society is similarly unsophisticated.

The implication of these types of assumptions is further complicated in relation to the current hot topic in Europe: integration. In Denmark, the Chinese (and the Turkish and the Vietnamese) are no longer populations far away, but citizens sharing the same nationality and society. Though no miscegenation laws or anti-Chinese immigration laws ever existed in Denmark, discrimination still exists on a societal level. Since the 1950s and the post-World War migrations, Danish unwillingness to hire foreigners prevented unskilled and skilled immigrants alike from breaking into the Danish labor market and away from ethnic businesses.

This trend has continued into the 21st century for Chinese-Danes. Statistics from 1994 show that the catering business employed 38% of all registered Chinese in Denmark. Even those who find jobs outside the catering business find them mostly in industries tied to their ethnicity, as Chinese acupuncturists, language teachers, or martial arts instructors. “In all these cases, their Chinese ethnicity is [their] decisive resource,” remarked Thunø, “The economics require the Chinese to continue othering themselves.”

A common argument for the case that certain immigrants are unassimilable is that they themselves choose not to identify with the host nationality, and self-segregate. But if the Chinese in Denmark are economically integrated in a way that requires them to continue in professions that highlight their otherness, where does this leave their prospects of “becoming Danish?”

Potential of Food to Change Perspectives

“Perhaps the question of becoming Danish is not the right way to ask,” says Thunø. “Why should the Chinese strive to become Danish when they can have several cultural identities at the same time?”

In this case, food is the perfect example of the balancing act between multiple identities all while losing none of the essence of either. Today, more and more restaurants are catering to the contemporary foodie scene, which demands authenticity and a global outlook. Indeed, we see it in the new wave of Chinese and ethnic restaurants in major cities that are elevating Chinese cuisine to dining standards on par with French, Italian and equally “prestigious” fares. In exciting developments, restaurants and venues are striving to diversify Chinese food beyond the predominantly Dim Sum (Hong Kong-nese) and Sichuan flavors familiar to Westerners.

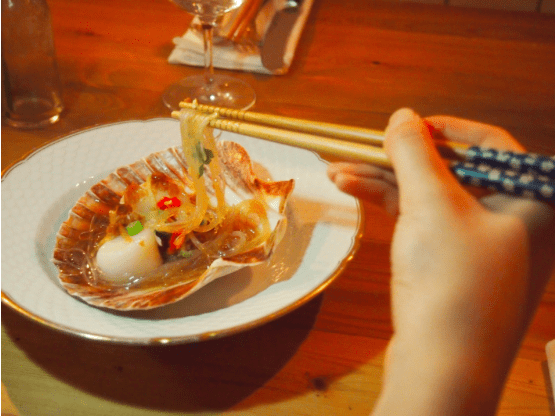

KeWei’s Kitchen is one of the new restaurants in Copenhagen testing the market for elevated Chinese food, offering undiluted flavors from all corners of China. Located in the meatpacking district, KeWei’s pop-up restaurant is open for dinner every Sunday and Monday night. The Copenhagen Post deemed KeWei’s Kitchen as “Chinese food at a Danish pace,” alluding to the slow, course-by-course dinner service, that marks a contrast to the fast service style of Chinese street stalls and buffet restaurants.

“I would say the concept is ‘China Uncovered,’” says KeWei, chef and owner of KeWei’s Kitchen and a native of Beijing who has spent the past six years working and studying in Europe, “It can be tricky because for Danes, they’re only familiar with the few fried, fusion dishes they’ve eaten before at takeaways.” In response, KeWei’s Kitchen offers a small, set menu that makes it easy for the inexperienced to explore food from all corners of China. The menu aims to expand the conception of Chinese food in Denmark both in terms of quality and regionally. “I want to make Chinese food friendlier to access and to broaden the perspective. It’s not just Sichuan food!”

Explore below a culinary roadmap of China (text continues after the graph).

Though less than a few months old, KeWei’s Kitchen has an established reputation amongst Danes and Europeans who have lived in or travelled to China, hungry for a savory reminder of their culinary adventures there. Nevertheless, introducing authentic Chinese food and culture to the general Danish population has been a challenge. Price is the first hurdle – as with all ethnic cuisines, it’s difficult to persuade diners to pay premium price for cuisines they associate with being generally cheap and low-quality. “Of course you will not pay high prices for bad quality food, but real Chinese food is not like that. Nothing here is deep fried.”

KeWei is optimistic that Danish perceptions can change to see that authentic Chinese food is healthy and fresh, and perhaps begin to have a nuanced view of China in general.

“Hopefully, [understanding of] Chinese [culture] can go beyond just food. Right now, hanging out at a Chinese restaurant is not cool. You don’t go buy Chinese products because you think they’re top-design.” For the future, KeWei has ambitions to utilize her pop-up kitchen to change this mentality and to create a trendy space that is a hip place to hang out. Not just to appreciate Chinese cuisine but also to see work and art by contemporary Chinese designers, an effort to counter the image of China as the source of tacky knockoffs.

Foodies Driving Dialogue

As both integration and foodie culture are pushed into the social spotlight, the economics and development of the ethnic food industry has become an insightful, even popular, lens through which we can explore society’s perception of and prejudices for certain minority groups.

In major cities worldwide, the modern appetite for exotic tastes is exploding the market for new cuisines and people are expanding their palates in ways unheard of 50 years ago. New restaurants like KeWei’s Kitchen strive to diversify homogenous culinary landscapes through a more representative and richer cultural experience. In addition to her informative menu, KeWei runs a blog to present more history and cultural context behind the food, for those who are interested. A more representative ethnic food scene can perhaps be the cultural ambassador we need in today’s globalized societies.