When I told my dad I was learning Irish, he reminded me of how my grandmother, who had moved from Cork, Ireland to Sheffield, England in the 1940s, developed dementia and forgot some English words. She used Irish words instead.

“Can I have some bainne [milk] in my tea?” she asked as we sat in the nonenal-scented armchairs of her care home.

Born in 1915, nana Maev was six when Ireland became independent. Her father, a non-Gaeilgeoir (non-Irish speaker) teacher and member of the Conradh na Gaeilge (Irish League) in Kilkenny, sent her to study at a boarding school in County Monaghan, up by the northern border, where she was taught entirely in Irish.

After graduating from university, where she met my grandad, she moved with him to England. Except for a few occasions that have made family history—such as when on a holiday in Ireland she told off some locals for badmouthing her oblivious children, or when at a party in Sheffield she explained to the inquisitive Gaeilgeoir birthday girl that her son, my dad, couldn’t understand a word she said—she barely spoke the language again.

“Why do you think nana stopped speaking Irish?”, I asked auntie Rita on the phone. Growing up in Italy, speaking English was what set me apart from my Italian friends. How could my own grandmother be willing to relinquish the language that was unique to her culture? “The thing is, lovie,” said auntie Rita in her unmistakable inflection, “I don’t have an answer to that. It was just something mother was taught in school.”

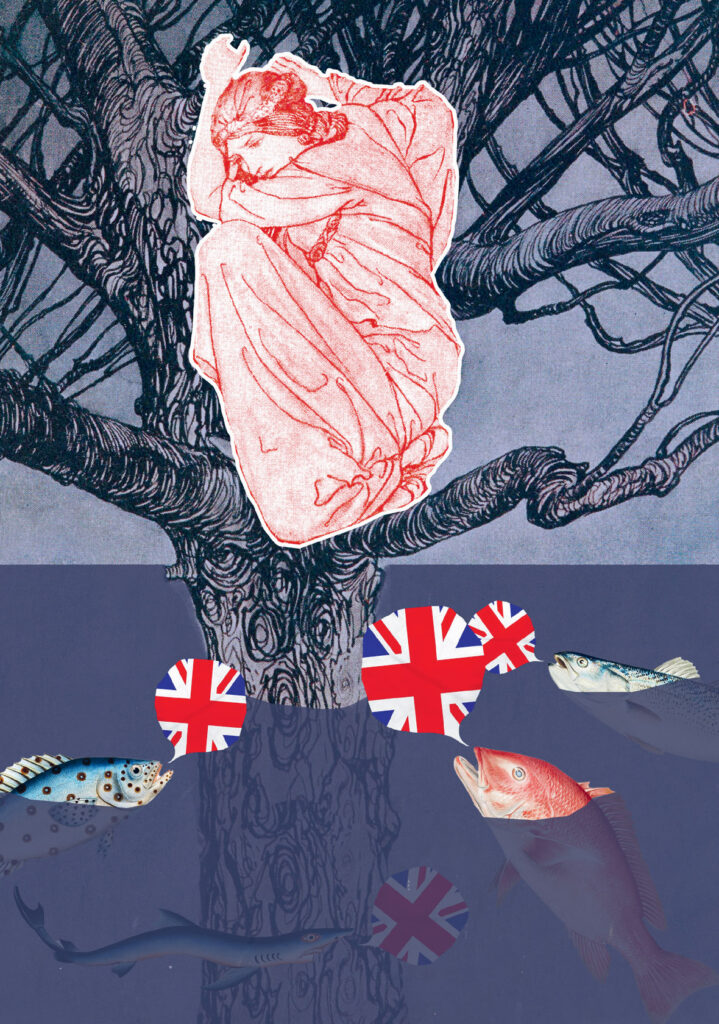

Many Irish don’t speak the native language as a result of the country’s long history of British rule from 1169-1921. According to the latest Central Statistics Office census, a total of 1,761,420 people in the country speak Irish, representing 39.8% of the Irish population. Of these, only 73,803 speak it on a daily basis outside of the school system; that’s under 2% of the total population.

Irish is listed as “Definitely endangered” in the UNESCO Atlas of World Languages in Danger. Though it was recognised as an official language of the EU in 2005, the institutions in Brussels have had a hard time finding enough people with the skills to translate and interpret between Irish and the other Union languages in the European Parliament.

Spoken for over 2,000 years, Irish is one of the oldest living languages in Europe, and was the object of a protracted campaign of linguistic repression starting with the 12th-century Anglo-Norman invasion. The 1366 Statutes of Kilkenny declared that people must take on English surnames or lose their property—which is presumably why my name isn’t spelt Ó Conaill today.

In the 16th century, commenting on the latest wave of rebellions, the English poet and Munster planter Edmund Spenser identified the erasure of the language as the key to achieving definitive subjugation of the Irish. In 1595-1596 he wrote: “For it hath ever been the use of the conqueror to despise the language of the conquered, and to force him by all means to learn his.”

During the Great Famine in the 18th century, many Irish speakers either perished or migrated. Still, the language continued to be a target of British repression until the 1920-1921 War of Independence.

“My granny remembered her mother going out into the field at night to burn her Irish songbook,” says Geraldine Holland, whose grandparents also moved from Ireland to Sheffield. “She was scared of the Black and Tans”—the Royal Irish Constabulary enlisted by the British government to suppress the Republican Army. “That’s so sad. Can you imagine burning your own culture?”

With independence, Irish was recognised as the first official language of the new nation, but this wouldn’t reverse the effects of the long debasement campaign. On the other side of the border in Northern Ireland, meanwhile, recognition of the Gaelgoiri, who make up 10% of the population, wouldn’t come until much later—with the 1998 Good Friday agreement marking the end of the thirty-year conflict between Loyalists, supportive of the British Crown, and Republicans, in favour of a united Ireland—and a proposed language act that would give Irish equal status to English is yet to be passed.

The humiliation of native languages is a strategy of psychological colonisation whose effects are even more powerful and long-lasting than the more visible ones linked to economic or political domination. Once the language of power is internalised, says Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, “you normalise the abnormal and the absurdities of colonialism, and turn them into a norm from which you operate. Then you don’t even think about it.” For years, neglect of Irish was an inherited behaviour that went largely unquestioned. There are signs this is changing today.

As of September 2020, there were 1.04 million active users worldwide—myself included—learning Irish on Duolingo. Almost a quarter were in Ireland. This reflects a popular resurgence of appreciation for Irish cultural symbols considered unfashionable by previous generations.

“There’s an increasing love for Irish,” says Dublin-based Irish-language broadcaster Wuraola “Ola” Majekodunmi. “It’s becoming increasingly part of the culture, it’s no longer linked to shaming, or thought of as useless. It’s an art.”

“It’s a lovely language,” says my cousin Holly in County Kildare, who like all children in the country studies it in school. She tells me it’s common to throw Irish words into English conversation. “But there’s too much pressure on exams, it’s not really about the culture. You learn things off by heart and don’t actually get to speak.”

Katie, my MMA-fighting hairdresser in Berlin, is from Galway and has similarly terrible memories of Irish class, but says she and many of her friends back home are rediscovering the language. I suggest their earlier lack of interest might be a colonial hangup as she cuts my hair. “I’d never thought of it like that. I suppose it could be.”

It’s no coincidence that a revival of traditional culture is happening today. “This is a generation figuring out the national identity post-economic crash,” says journalist Una Mullally in Dublin, pointing to the 2008-2009 crisis. This put an abrupt end to the Celtic Tiger economy and ushered in a season of progressive social change, as the biggest under-analysed factor behind the phenomenon.

Events such as the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising, celebrating the frought struggle for independence, and Brexit, rekindling for many hopes of a united Ireland, have also played into “a sense of patriotism that is not rooted in sectarianism,” Mullally continues. “We have moved on from the insecurities due to the traumas of colonisation.”

“For so long too many people were tied up in that colonial mindset,” Majekodunmi agrees. “Now slowly but surely they are coming back to loving Ireland for what it is.” From Irish-speaking meetups across the country, the “pop-up Gaeltacht,” to irreverent rap hailing from Belfast, Irish is not only alive—it’s become cool. “I can see a future for the language where it’s going to be more vibrant, more diverse, it’s going to keep going and growing bigger,” says Majekodunmi.

The pestering green bird on my phone screen is reminding me it’s time for my daily Duolingo exercises. I still have a long way to go, but I like to think that, if nana were still around today, I could finally pass her the milk.