In the autumn of 2017, Orion would go to a youth centre in downtown Cologne every day, protracting his stay until closing time. The queer migrant, who was only 17 at the time, lived in a refugee camp on the outskirts of the German city. The youth centre had become the only place where he could let his guard down, shrug off the thick air of the shelter and have a good chat with his peers.

Yet even there, something was not quite right. “I felt like an outcast. I had just arrived in Germany and I didn’t speak the language,” he recalls over the phone. “As queer youth, the other participants were supposed to resemble me, but it was hard to relate to local people whose life experiences had so little in common with mine.”

It was at that time that he met Rob and Vinz, who, as Italian migrants, had gone through their own traumatic experiences before arriving in Cologne. They too were struggling to feel part of the organisation. After a few months, Orion had the idea to form a group for queer refugees. He hoped that by no longer being the exception, but the rightful members, future participants wouldn’t have to experience the same feeling of isolation he had known.

By April 2018, Spektrum was an official youth group with a physical space in Kalk, a Cologne neighbourhood on the right side of the Rhine river. At first, Orion attempted to run it on his own, but soon responsibilities started to pile up. With a to-do list that goes from applying for funding and all logistics regarding events, to selecting trainers for workshops and making sure they’re sensitised towards racism, Orion turned to Rob and Vinz for help. Ever since, the three have been at the helm of the queer group—which today counts 15 members.

Spektrum has since become one of the few self-organised LGBTQ+ migrant youth groups in a country where it is notoriously difficult for vulnerable people to engage with bureaucracy without assistance. For Lilith Raza, an LGBTQ+ activist and project manager at Queer Refugees Deutschland, a federal project connecting and advising a network of roughly one hundred organisations across the country, self-organised groups like Spektrum are an anomaly in the German social work landscape. Their day-to-day handling is often too demanding for people with limited resources, especially if they are amid draining processes, like seeking asylum or transitioning.

“First, you’ll need an email address; second, you’ll need board members; third, you’ll need a legal status,” Raza enumerates, mentioning only some of the obstacles deterring migrants and refugees from self-organising. “Along with funding, language is also a huge barrier, with all that legal jargon that, frankly speaking, even Germans don’t understand.”

Raza experienced this with Queer Refugees for Pride, another network she has contributed to. Faced with the decision of whether to transform it into a full-fledged association or leave it as a looser network—with a considerably less significant administrative burden—they opted for operating it from within already existing structures. “We were not ready for all the paperwork, let alone the expense that forming an association from scratch implies because everybody is already juggling political activism and personal life, which is a lot to deal with.”

Spektrum’s autonomy, too, is conditional upon the support of a mother organisation. The Cologne-based NGO In-Haus was willing to offer the group the right to rely on its legal status, through which they can benefit from state grants. Although the group has grown increasingly self-sufficient in terms of administrative capability, Orion admits that it would have probably never seen the light of day had he not been helped every step of the way. But not many established NGOs are ready to delegate power to vulnerable groups, and that’s where part of the problem lies.

Queer refugee groups operate on the assumption that at times, organisers may be caught off guard by their experience of trauma or personal administration problems, and that someone else will have to step in. “It’s more of a ‘who can do what’ situation,” Orion explains, “because we can never be sure what our mental health will be like at a given time.”

From an early stage, the three friends understood that they needed to discard a hierarchical structure because their way of functioning would have simply made it unsustainable. But instead of perceiving it as a shortcoming, they claimed it as a foundational part of their identity. “Traumas have made us who we are, and we now need to help each other,” Orion says.

The activists have shifted the stereotypical narratives that portray refugees to be pitied and started to vigorously advocate for the spread of self-empowering methods across LGBTQ+ migrant communities. Nevertheless, authorities remain blind to the primary role played by trauma on the way queer refugees interact with social workers and authorities, failing to capture how these reverberate on their journey to integration. Many women and trans women who have experienced male physical violence, for instance, cannot tolerate remaining in a mixed safe house, because their presence inevitably triggers painful memories.

“The truth,” Orion says, “is that social workers often lack a proper understanding of our situation, but they still try to solve our problems and help us make decisions that will impact on our entire life.” “Instead,” he continues, “they should be empowering and supporting migrants to be self-empowered, self-sufficient and independent individuals who can solve their own problems and take their own life decisions.”

Reflecting broader society, social spaces specifically conceived to welcome migrants and refugees, like shelters or accommodation centres, are often marked by heteronormativity. Instead of finding a safe haven, queer migrants are once again forced to hide their sexual preferences and live in fear of being found out as they did back home, believing that being open would cause their fellow asylum seekers to reject them. “It’s something you immediately feel in the air, that makes you feel uncomfortable and wary of the questions that will be asked around your sexual orientation,” says Nina Held, a researcher and co-founder of the Queer European Asylum Network.

For Mengia Tschalaer, co-founder and coordinator of the same network and a professor at Bristol University, underestimating the violent implications a heteronormative space has for queer migrants can have serious consequences. “We are talking about a constant fear, and it makes no difference if there’s no direct threat. It’s the fear of being violated, coupled with trauma and a huge amount of insecurity around the legal status they are missing,” Tschalaer says.

Failing to address the issue has an impact on the entire system, because a particularly hostile environment may discourage migrants from seeking help when needed. “Most people don’t even dare to go to the police, either because they are afraid of being deported or because they have pre-existing traumas towards law enforcement,” Tschalaer explains. “All that combined adds up to the invisibility of queer migrants and refugees.”

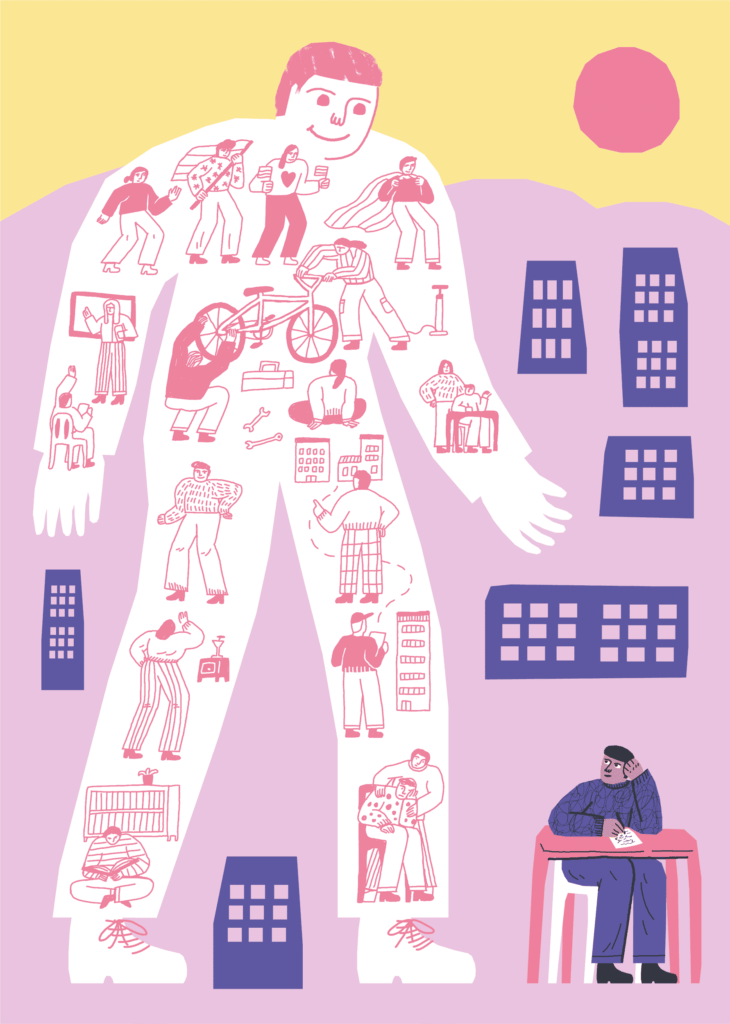

Autonomous and horizontal organisations like Spektrum can offer a truly safe space for a community that, because of a multi- layered identity, finds it hard to develop a sense of belonging in most societal spaces.

Today, four years since its foundation, Spektrum has already accomplished more than many NGOs. It was invited to participate in the council organising the Cologne pride in 2019—the second-biggest in Europe after the one in Madrid—and advised the same city on the lack of social services in less privileged neighbourhoods.

But for the group led by Orion, Rob and Vinz, the biggest source of pride is to be the living proof that—no matter their trauma and day-to-day struggles—queer migrants can play an active role in achieving the life they sought when they came to Germany.

Taim, who joined Spektrum a couple of years ago, says that being part of a self-organised group was a relief after their past experiences with more established NGOs. “Because we all face the same issues and share similar stories,” says Taim, “the organisers of Spektrum are much more aware of our needs.” The groups can also be more inclusive because no specific rules are in place and paperwork is kept to a minimum. “We are just a bunch of people who want to hold activities and learn from each other. We may not be the most organised, but we have the passion it takes to do something together.” This stands in contrast with the way most NGOs work, where participants are asked to fill forms, show their commitment by volunteering for a certain amount of time and only eventually become part of the team.

If the three friends are the de facto organisers, coming up with ideas for future projects and setting up the logistics, Spektrum’s members see them as peers. The fact that they’re all in their twenties certainly helps. And the activities run by the group tend to closely reflect the needs of their community for the simple reason that, as queer migrants themselves, organisers only have to draw on their own experience. Far from tabling projects with pretentious names and loose objectives, their activities are much more relevant—such as a humble workshop on how to repair bicycles, which is something vital for most migrants in bike-loving Germany.

“To us, integration has nothing to do with learning the Chancellor’s name or passing an integration course,” Orion says, referring to the subjects included in the integration course certificate, a mandatory step for refugees once their asylum request gets approved. “Integration is taking part in democracy, working together for our communities, and having the voice, power and resources to make decisions about our own lives.”