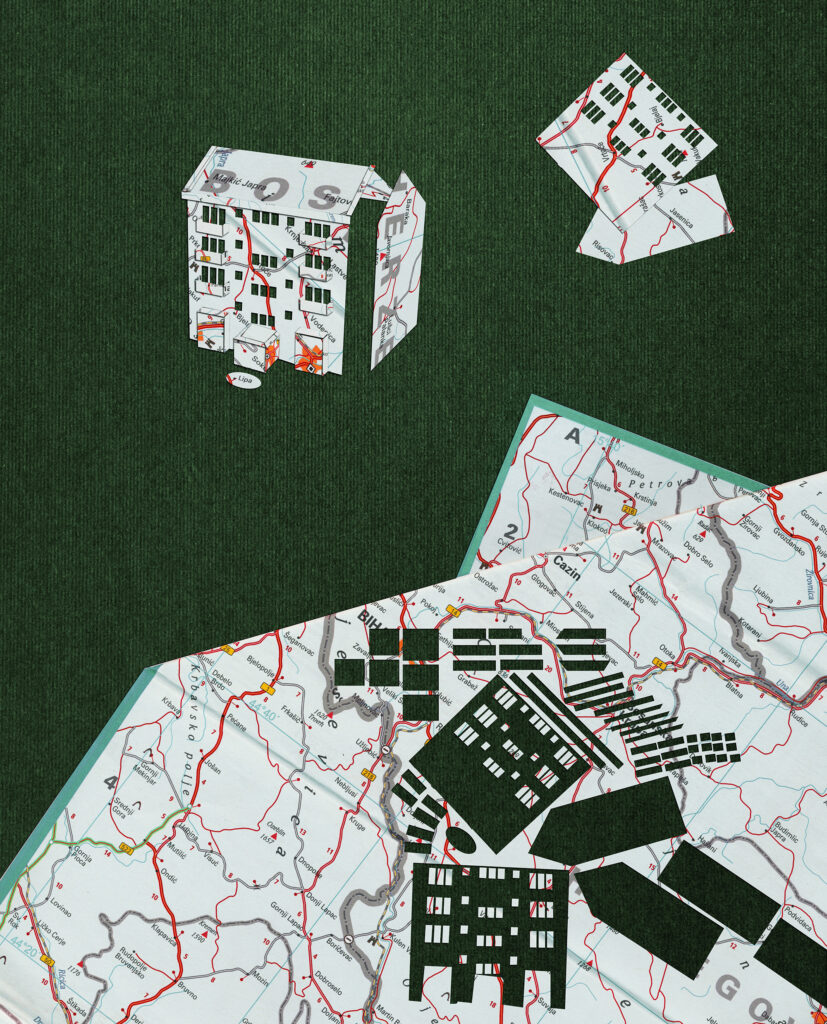

Snow is falling over Lipa, a temporary camp for migrants, 30 kilometres away from the city of Bihać in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It snowed last night and it’s snowing again tonight. It’s not falling in my neighbourhood yet— maybe just a snowflake or two— and I’ve never looked forward to it less. After Lipa, snow will never look the same again. So I’m walking through the city, trying to make sense of our becoming so cold-hearted.

It was not so long ago that the first groups of migrants began to arrive here, in the region of Krajina. People came together to help the brothers that the whole world has forgotten. That’s how they talked—ready to give the whole world a lesson in humanity. And they did: the restaurants cooked and handed out food, individuals offered accommodation, and the media dutifully fol- lowed all of this. Many proudly read of their heroism on the local news portals.

Over time, stories about helping hands decreased and the number of arriving migrants increased. I can’t precisely determine the moment in which the dissatisfaction with migrants began. What used to be a driver of solidarity—because these people were at the end of the world, left behind and forgotten by everyone just like the people from our region feel forgotten by the central government in Sarajevo—became a factor of objection. Now I’m seeing how that old wound of Sarajevo’s lack of care gave birth to a certain hostility in citizens who watch, without remorse, the freezing of at least a thousand people. There were summers when full buses arrived every day. At a certain point, Krajina decided it didn’t have enough room. It cannot and will not feed an army of the unloved from its own resources.

Perhaps the beginning of this fear was when they started to be called migrants. As long as they were refugees, we could have identified with them: we all remembered the refugee blankets covering those forced to leave their home during the Bosnian War from ‘92-‘95. Things changed when society focused on the geographic coordinates of countries at war and those that were not. Solidarity began to melt. It seems that certain words lead to limited rights. They determine to what extent you 79 have the right to dream and what or how much you will be given in life. If you are a migrant, according to that classification, you get less than a refugee.

Maybe it was the moment when someone complained: “They stole our crops.” They were hungry. Do we remember the last time we were so hungry? Perhaps it was when parents became frightened for their children who could not play outside because they feared migrants—even though migrants clashed only with each other. We seem to have forgotten about our world of violence. We forgot how schoolchildren not only participate in bullying but even record it. We are not afraid of our kids, but we are afraid of migrants.

Maybe it was the moment when someone exclaimed: “What about keeping our streets clean and safe?” And what happened was what happens in all cities that are proud of being clean. When stray dogs occupy the city park—scruffy, dirty, stinking and hungry—you open a shelter for dogs and put them into concrete cages. On the outskirts of the city, far from our eyes. Where no one can smell them, and their population can decrease in controlled conditions. Likewise, people will say this needs to be done to mi- grants, to move them out of the city centre.

However, when you have travelled so far, your legs will not let you remain in the security of the reception centre. They wander around, seek, scout—restless until they reach the air of the European Union. Only this pristine air of the Union will set you free. Especially if it’s just a kilometre away from you.

And as I walk, I see and hear stuff. I look at the scouts peering over the edge of the border of the camp. Their eyes assess the density of our forest—a forest not as dense as it used to be. Many of its trees were cut down mercilessly. I don’t know if the scouts know that the Croatian police received “equipment for the effective oversight and protection of European borders”—a donation from the Union.

In some cases, the cruelty is very obvious, like during citizen protests or when agents are herding migrants into tents. In other cases, it is more sophisticated, just like the border control equipment. The EU gave us money to bear the weight of the migrant crisis; to take people in and not cause too much of a stir. Now, from a distance, they judge that we are inhumane. But they did the maths and calculated that it’s better to pay us than to have to deal with migrants in their countries.

But that does not get us off the hook. I love my people, so I want to justify the actions of our generation, but there is no justification for this. That’s why I walk: until I can find a good person.

And goodness always finds us instead. For example, yesterday, my tiny neighbour—a widow who lives alone—was returning from the city with two pillows bigger than her. The salespeople are back in town. They offered her a welcome gift and a product showing without obligation. She explained nicely that she is retired with a minimum pension of 380 DEM—190 euros. She has no money to throw away. In the end, she did not have the heart to refuse them. And she bought those two pillows. The retired get special discounts, they can pay in instal- ments; she tells me all of this as if to ease her conscience. Like it’s not for her, it’s for when her son comes from America, and she has not seen him for two years. He should have them—no one uses those old feather pillows anymore.

As we are getting closer to home little by little, the familiar face of a child jumps out in front of us—one that has been “around” for the past couple of months. She looks at him worriedly and asks: ”Son, are you okay? How are you doing?” “Here, take this,” she says, starting to rummage through her pockets. He’s uncomfortable and shakes his hand, gesturing, no—I don’t need it. “Take it,” she repeats, but he’s already leaving. Now she’s shouting after him, and waving for him to come back. And he does come back, puts his hand on his heart and tells her with that gesture “Thank you and no need.”

I’m guessing he feels that he’s already taken too much, all in his quest to reach the promised German land. Now he’s here and doesn’t have the heart to take something from a small, dear old lady. But she doesn’t give up and asks: “Where do you live? Is it in the big house under the road?” She mimes the shape of the house and the path with her hand. He nods that it is indeed the house under the road, but on the left rather than the right side. He’s not alone there and she knows it, so she’s asking him further, “Where is that tall, Black guy that was always with you?” He doesn’t understand her. She shows with her hand how tall he is and that he has a lot of hair—and he gets it. He shakes his head. It’s obvious that the tall guy is no longer there.

How could he explain to her that the tall guy passed through the mousehole and that we will not see him anymore—if he got lucky. It’s a story on repeat. There are some well-known faces in the city. We get used to them, they learn a bit of our language, and then one day they are just gone. It takes a few months, sometimes a lot of futile attempts. Today, each of us goes their own way. I think maybe in this world there 81 are enough windows to look upon someone else’s child as your own. Only then do I realise that this child is walking around in just a red t-shirt. My mobile phone shows that it’s two degrees outside and almost a thousand of someone else’s children are accompanied by snowflakes outside their tents. There is no justification for our behaviour.