Plain text:

Forget getting high. Hemp is praised for its versatility. It is a superfood full of proteins—ideally suited to vegan regimes—and can be transformed into medicine, textiles, and construction material. Hemp also absorbs more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases, which means it is a precious carbon sink. It is an organic fertiliser and soil loosener, making it a treasured plant for farmers.

Hemp and marijuana both come from the same species, the cannabis plant. But hemp contains just 0.3% or less of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component in cannabis. In Germany, some varieties of hemp are authorised if their THC concentration does not exceed 0.2%. In marijuana, the average level is around 15%.

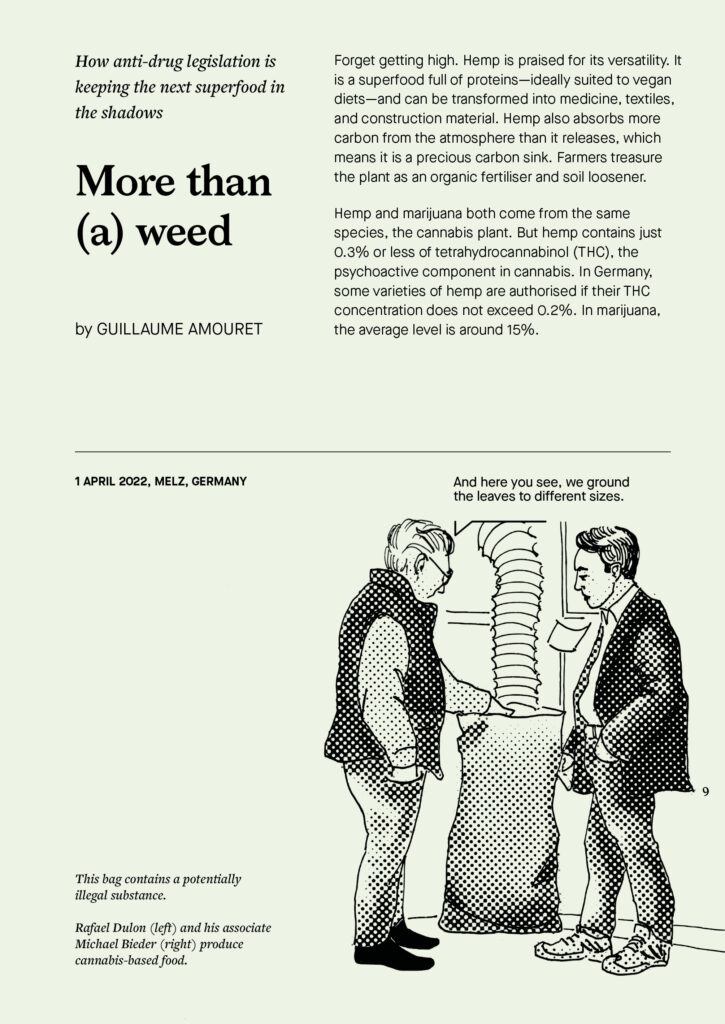

1 April 2022, Melz, Germany— “And here you see, we ground the leaves to different sizes.” This bag contains a potentially illegal substance. Rafael Dulon (left) and his associate Michael Bieder (right) produce cannabis-based food.

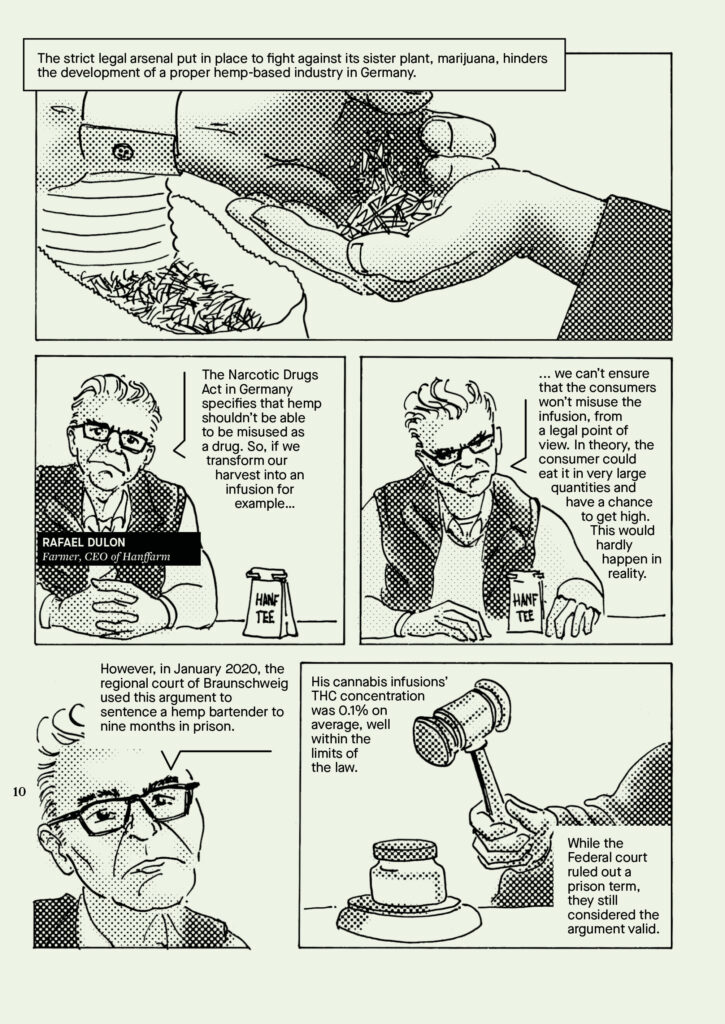

The strict legal arsenal put in place to fight against its sister plant, marijuana, consequently hinders the development of a proper hemp-based industry in Germany.

Rafael Dulon, farmer, CEO of Hanffarm: “The Narcotic Drugs Act in Germany specifies that hemp shouldn’t be able to be misused as a drug. So, if we transform our harvest into an infusion for example, we can’t ensure that the consumers won’t misuse the infusion, from a legal point of view. In theory, the consumer could eat it in very large quantities and have a chance to get high. This would hardly happen in reality.”

However, in January 2020, the regional court of Braunschweig used this argument to sentence a hemp bartender to nine months in prison. His cannabis infusions’ THC concentration was 0.1% on average, well within the limits of the law.

While the Federal court ruled out a prison term, they still considered the argument valid.

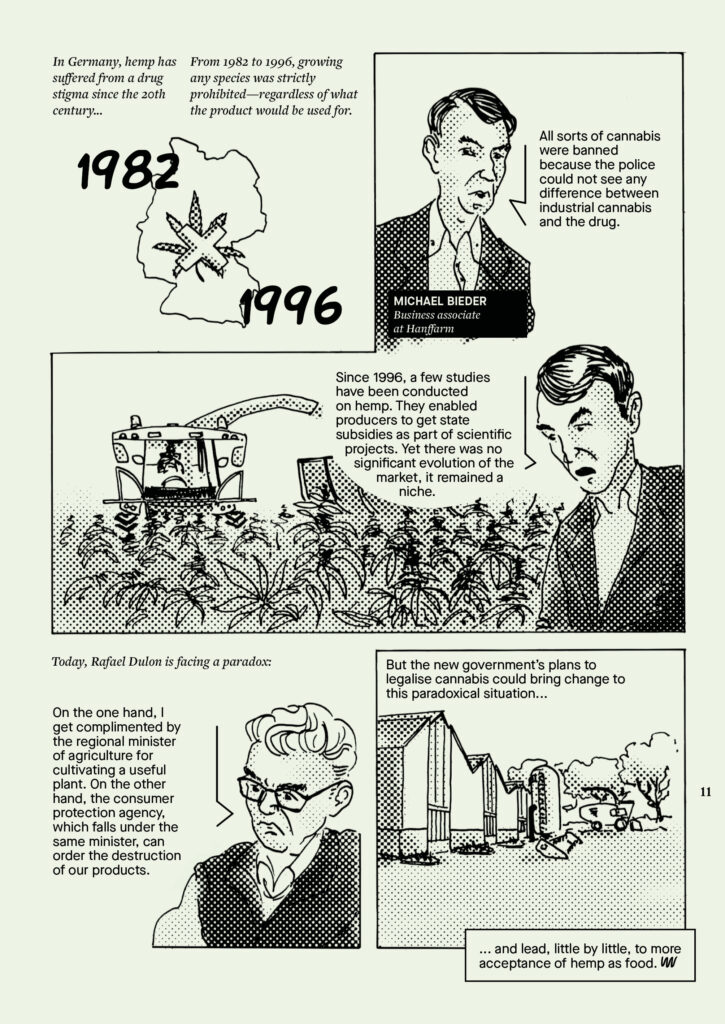

In Germany, hemp has suffered from a drug stigma since the 20th century: from 1982 to 1996, growing any species was strictly prohibited—regardless of what the product would be used for.

Michael Bieder, Business associate at Hanffarm: “All sorts of cannabis were banned because the police could not see any difference between industrial cannabis and the drug.”

Michael Bieder: “Since 1996, a few studies have been conducted on hemp. They enabled producers to get state subsidies as part of scientific projects. Yet there was no significant evolution of the market, it remained a niche.”

Today, Rafael Dulon is facing a paradox: “On the one hand, I get complimented by the regional minister of agriculture for cultivating a useful plant. On the other hand, the consumer protection agency, which falls under the same minister, can order the destruction of our products.”

But the new government’s plans to legalise cannabis could bring change to this paradoxical situation, and lead, little by little, to more acceptance of hemp as food.