If you are ever called upon to visit your ailing grandmother in the woods, beware. It might only be a 30-minute walk, but there are many dangers along the way. If you remember one thing: do not leave the path. Even if there are beautiful flowers to pick for a fresh bouquet.

***

“Good day to you, Little Red Riding Hood.”

“Good day to you, Little Red Riding Hood.”

“Thank you, wolf.”

“And what are you carrying under your apron?”

“Grandmother is sick and weak, and I am taking her some cake and wine. We baked yesterday, and they should be good for her and give her strength.”

“Little Red Riding Hood, just where does your grandmother live?”

- Rotkäppchen (Little Red Riding Hood), The Brothers Grimm, 1857.

***

We know how the popular fairy tale goes. Luckily for Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother, the wolf did not care much for chewing and a local hunter, recognising grandmother’s loud snoring as odd, came to the rescue. In this story, there was a happy ending for everyone—but the wolf:

“The huntsman skinned the wolf and went home with the pelt,” the tale by the Brothers Grimm reads. “The grandmother ate the cake and drank the wine that Little Red Riding Hood had brought. And Little Red Riding Hood thought, ‘As long as I live, I will never leave the path and run off into the woods by myself if mother tells me not to.’”

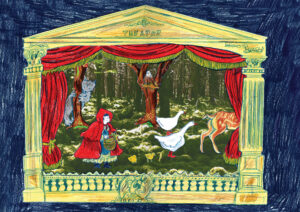

Little Red Riding Hood is not the only fairy tale character to have had an unusual encounter while roaming the wild. In folklore, forests are often portrayed as magical or enchanted places inhabited by whimsical fairies, mischievous imps, and inscrutable ancient beings of all descriptions. At other times the forest is a dreamy sanctuary: a space of safety, escape and wonder.

But the woods can also be dark and dangerous places where light barely penetrates and evil—in the form of a wolf, a witch or an ogre—lurks. Gilgamesh and Enkidu travelled into the cedar forest to fight monsters in the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest piece of literature in the world. Norse mythology warns even the gods against getting lost in the myrkviðr (myrk: dark and viðr: forest in Old Norse). Known as “Mirkwood” in English, the word was popularised by J. R. R. Tolkien in modern fantasy literature where the dark and enchanted forest is a mainstay.

Forests have long been places devoid of “civilisation” and “the rule of law.” In Roman law, the word forestis designated all uncultivated land with no clear owner as belonging to the emperor. Later, Merovingian and Carolingian kings took over this term—not to refer to a place with many trees, but to refer to the wilderness. However, these “forests” were rarely as dense and dark as the folk tales of yore would have us think. In reality, these landscapes were much lighter and more open than the ones we know today.

Little Red Riding Hood had run after the flowers. After she had gathered so many that she could not carry any more, she remembered her grandmother, and then continued on her way to her house. She found, to her surprise, that the door was open.”

Little Red Riding Hood had run after the flowers. After she had gathered so many that she could not carry any more, she remembered her grandmother, and then continued on her way to her house. She found, to her surprise, that the door was open.”

If you have ever gone to the forest to pick flowers, chances are that you came home disappointed. When trees live close together, their days consist mostly of competing with each other for the scarcest resource available: light. Every unoccupied square metre in the forest canopy is precious real estate, soon to be assumed by the ever-expanding roof of leaves and branches. Less than 5% of sunlight actually makes it to the forest floor. If you want to find flowers in the woods, you best try your luck in the verges of the road leading there, or next to the visitors’ treeless car park. Only in early spring, when most trees are still bare and sunshine reaches the ground, small, precious flowers like the common dog-violet or wood anemone make an explosive—if brief—appearance.

So where did Little Red Riding Hood find all those flowers? Fairy tales are full of elements that are not exactly true. But out of all the details the Grimm brothers fabricated, Red Riding Hood’s bouquet might be the most plausible. The forests of former times contained only a fraction of the trees found in the forests of today, leaving more space for meadows with plants and flowers.

In the late 1970s, a Dutch ecologist named Frans Vera noticed that in the polder province of Flevoland—a reclaimed area of low-lying land that used to be submerged by the sea—a gaggle of geese were visiting to rest and moult during their trek from Siberia. Thousands of migrating birds happily feasted on the endless reed beds in the area. “The geese opened up the reed beds and did something unimaginable,” Vera explains during our interview with him. “They changed them back into open water. They created the habitat for all kinds of other bird species.” During his studies, Vera had learned that grazing animals follow the landscape. But in Flevoland, he witnessed how grazing animals steered the landscape.

At the time, succession theory was widely accepted among biologists and ecologists. Leave a patch of bare soil alone, wait long enough, and—after a succession of plants, shrubs, and then trees—a forest will eventually appear. Human interference was presumed to be the only force strong enough to halt this process. Supposedly, wherever there were no humans, there was a forest. A gargantuan closed-canopy forest that covered most of Europe.

As Vera realised, this theory completely sidelined a key player that changed everything: the multitudes of grazing animals roaming free. Auroch and tarpan—the extinct European ancestors of today’s ox and horse—as well as bison, moose and red deer had been eating so many seedlings and saplings that they interfered with natural succession, and slowed it down for thousands of years.

Succession theory had seen large grazers in a different light. Rather than an inherent part of the ecosystem—where they created habitats for other species by keeping the landscape open—they were deemed a destructive force, eating everything up. So, in order to protect the forests, the grazers had to go. Densities of large herbivores were deemed too high and “unnatural,” which resulted in their removal or culling under the banner of nature conservation. Slowly, the forest canopy closed.

Large herbivores were clearing space, and clusters of trees and spacious meadows balanced each other out. Forests were not endless collections of trees—they were endless collections of biotopes—home to all kinds of plant and animal species. They were varied landscapes where biodiversity thrived, flowers grew, and butterflies nectared. The cool shade and a damp forest floor, alternated with sun-dried grass and prickly shrubs, created countless niches for organisms to thrive in. Chances are that Little Red Riding Hood could have indeed found her flowers in the meadows and woodland edges that were all part of “the forest.” Vera’s new theory shook the discipline of ecology to its core.

Of course, Vera’s early observations on geese were just one example of animals steering the landscape. He needed to see for himself what would happen when large grazers dictated the land. Surprisingly, the Netherlands—one of the most densely populated countries in Europe—was willing to give Vera’s experiment a shot. In 1983, 32 Heck cattle were released in a new natural reserve named the Oostvaarderplassen, followed by wild Konik horses. Both breeds were selected by Vera due to their likeness to their now-extinct ancestors. Later, red deer were added to the mix and although European bison were considered, they did not make the cut. From 1995 until 2018, these animals were largely left alone, which allowed conservationists to see how nature would develop in tandem with large grazers

Vera still recalls the reaction to his plan when he proposed it in 1980. “I was hoping to attract white-tailed eagles to the Oostvaardersplassen, but everyone said I was mad,” he shares in an interview in the book Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm by Isabella Tree. In 2006, the first breeding pair made the reserve their home. White-tailed eagles have been breeding in the Netherlands ever since, growing to a population of 67 in 2019, after centuries of local extinction. Today, from the train riding from the city of Almere to Lelystad alongside the reserve, one can see tens of thousands of geese and lapwings taking to the skies when a white-tailed eagle mounts its attack. Other birds of prey satisfy their needs with smaller targets, scouring the terrain from the air for rodents. A nature documentary from 2013 about the Oostvaardersplassen, The New Wilderness, was the first of its kind to be screened in cinemas in the Netherlands. It shows foxes—normally known as nocturnal animals—hunting during the daytime.

Word spread beyond the Netherlands about this former seabed turned bustling natural reserve. In the UK, Tree and her husband Charlie Burrell were struggling to keep their farming business at Knepp Estate in Sussex going in the early 2000s. Having inherited 3,500 hectares of land—an area a bit bigger than London’s Heathrow Airport—they were making a loss year after year. Looking for a way out, their curiosity piqued when they heard about the Oostvaardersplassen; a place where natural processes were creating a dynamic ecosystem.

They took the leap and managed to secure the funding to start a process-led conservation project. By slowly allowing their land to transform as it pleased, with herbivores keeping the landscape open, Knepp Estate has become a fascinating example of what nature is capable of when left to its own devices. In her book Wilding, Tree admits it was sometimes difficult “to do nothing,” especially when things are not going as you would hope. Yet, that was precisely the point. Since taking their hands off the wheel, “wilding” efforts at Knepp Estate have brought many critically declining species to the area, such as the nightingale, turtle dove, purple emperor butterfly, and the rare barbastelle bat. Due to the lack of livestock wormers and parasiticides in the grazers’ diets, cowpats have become a nirvana for countless species of dung beetle.

“Open up the box, allow natural processes to develop, give species a wider scope to express themselves, and you get a very different picture,” Vera says to Tree in her book. “This is what the Oostvaarderplassen is all about. Minimal intervention. Letting nature reveal herself. And the result is an environment we know nothing about.” None of the endangered or rare species that appeared at Knepp Estate were planned for with carefully crafted conservation road maps. They just showed up and stayed.

What we see at the Oostvaardersplassen and Knepp Estate is that nature is quite capable of looking after itself when given the opportunity. Perhaps light wasn’t the scarcest resource in the forest after all. It may well have been the freedom to develop and heal itself, without humans maintaining an uneasy command over dynamic systems whose natural developments are impossible to predict.

Little Red Riding Hood’s woods do not offer a blueprint for saving nature. They serve as a reminder that the forest lives happily ever after when we do not force it to work for us. In the face of climate change and biodiversity decline, this knowledge swings both ways. Nature is flexible and capable of bouncing back, but it needs a certain degree of autonomy to work its magic. In other words, an ecosystem cannot fix itself if we will not let it. The results achieved by providing a breather to damaged landscapes or allowing ecosystems to spring up out of the blue—be it from a former seabed or farmland—show that we do not need all the answers in advance. Forests maintaining themselves are a tale as old as time.

The end

The end