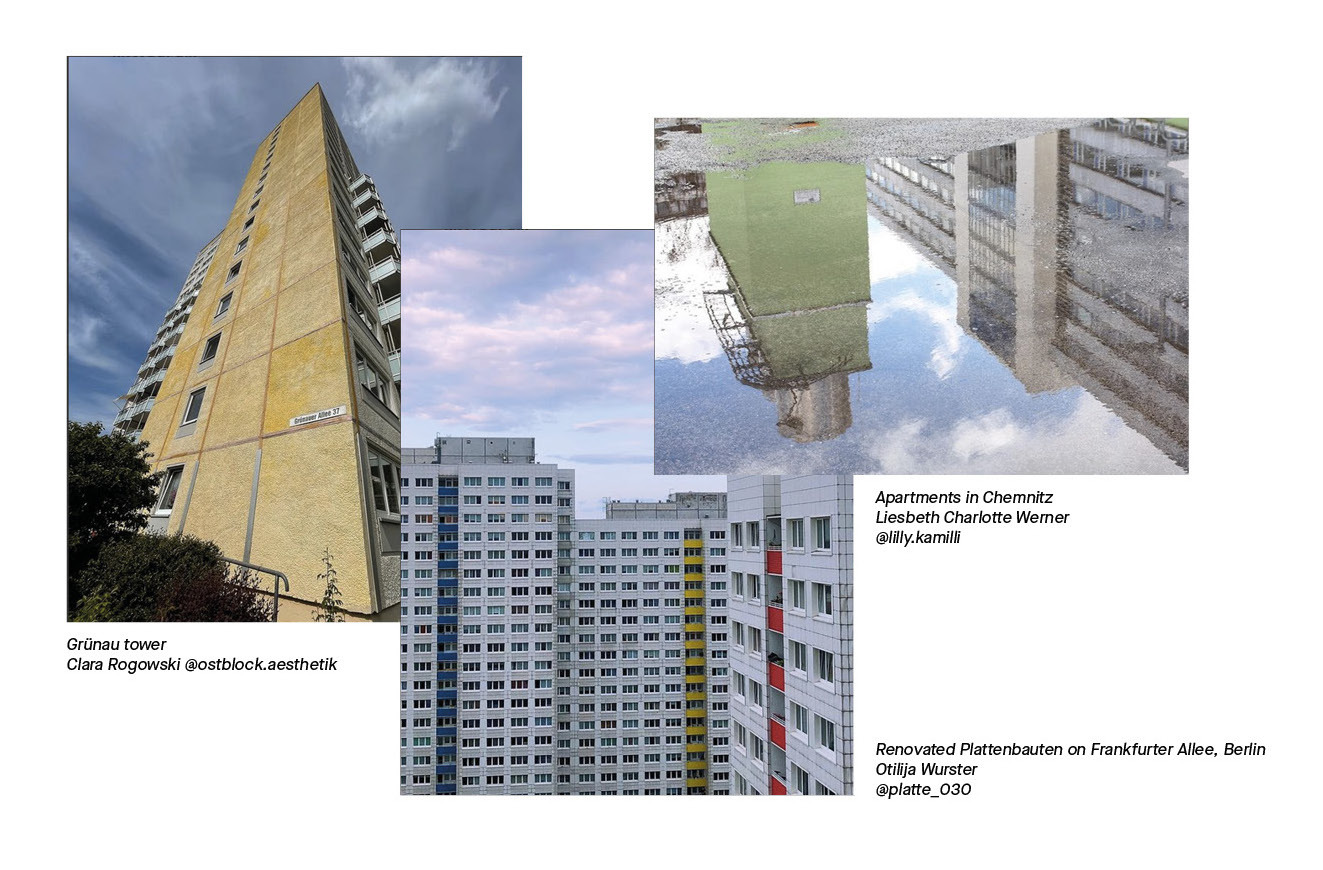

One sunny afternoon in June, Clara Rogowski stood at the base of a 16-storey apartment block on the outskirts of Leipzig. As she pointed her iPhone upwards, her screen framed a familiar motif. Rough washed-concrete panels divided the near wall into a grid that stretched to a sharp point against a pale cloud-wisped sky. “As an East German person, you sort of have that in your identity,” she said. “We all know these GDR blocks.”

In the strict sense, Rogowski, a 23-year-old university student, is not East German. The German Democratic Republic (GDR) ceased to exist in 1990, well before she was born. Still, the visual language of its modernist architecture has lodged itself deep inside her. She finds the concrete housing blocks ubiquitous across the former GDR—Plattenbauten (“panel-buildings”) in German—beautiful. Twenty years ago, that would have been nearly unthinkable. But Rogowski’s generation looks differently upon the architecture of its grandparents.

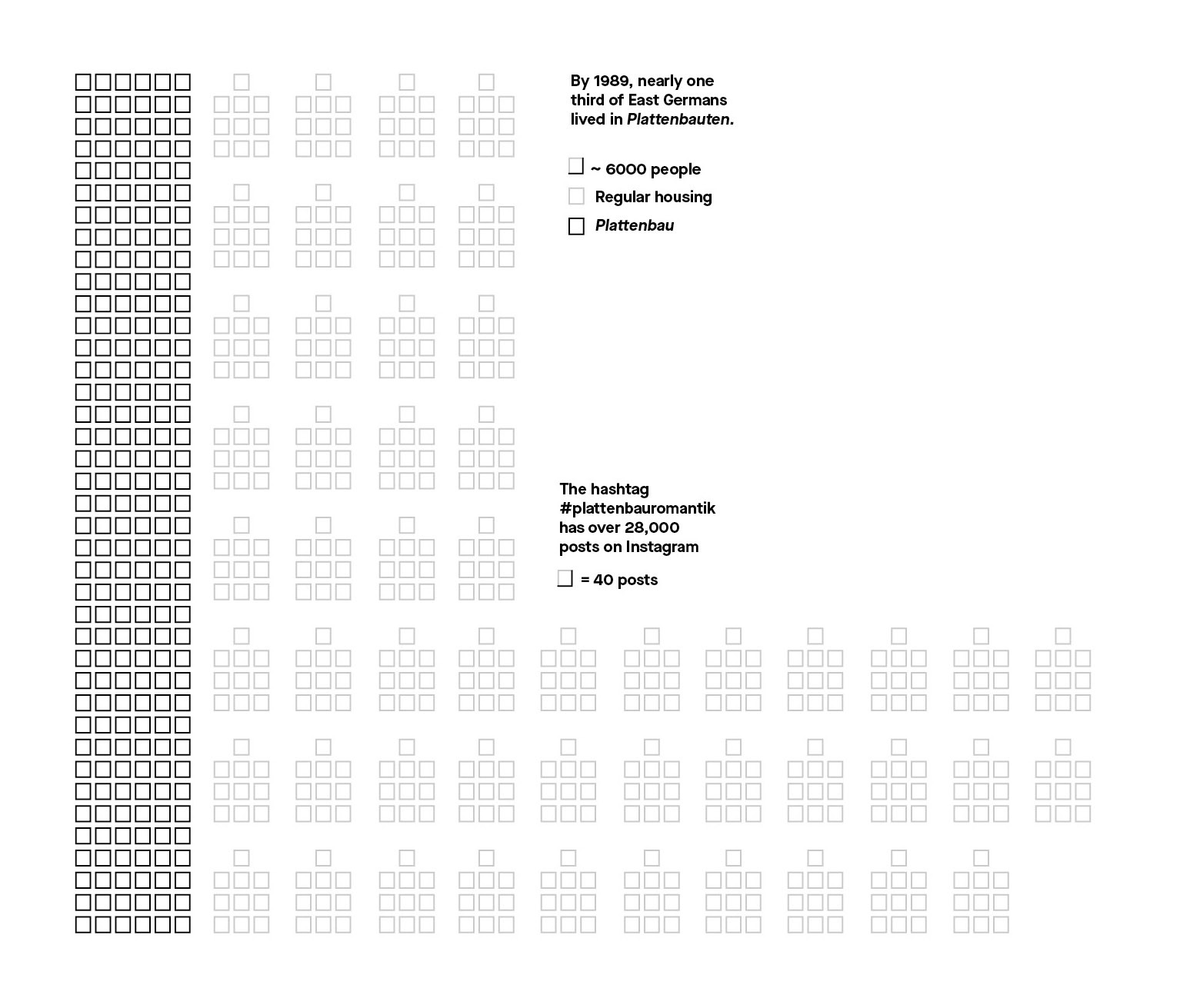

A few days later, Rogowski uploaded the photo to her Instagram account, where she regularly posts images of Plattenbauten. She’s part of a growing community of millennial and gen-Z amateur photographers devoting their accounts to GDR modernism. The hashtag #plattenbauromantik has over 28,000 posts on the platform. It is used beyond the German-speaking world, often by the Russian or Polish accounts that inspired the German revival.

Rogowski lives in a Plattenbau in Grünau, one of the massive housing estates built in the GDR on the outskirts of Leipzig. Throughout the 1960s, and increasingly in the 1970s and 1980s, the East German government constructed nearly two million apartments in Plattenbauten, which are composed of concrete panels stacked one on top of another. Though some now see their spare grey and brown walls as symbols of the socialist regime that constructed them, the GDR’s main goal in its housing construction was not aesthetic. Rather, it was to build as much quality housing as quickly and cheaply as possible: concrete turned out to be the best solution. When it was built, having an apartment in Grünau was a privilege. Central heating, a private bathroom, and hot water were luxuries for many. By 1989, nearly one third of East Germans—over four million people—lived in Plattenbauten.

Reunification plunged the Plattenbau into disfavour. Modernism was already sliding out of fashion in East Germany even before the Wall fell, as it had earlier in the west. New federal programmes began to subsidise the renovation of 19th-century tenements and the construction of single-family homes. People suddenly had the chance to live in a private house with a garden or a spacious renovated apartment with high ceilings in the city centre, options they never had before. The once coveted Plattenbauten were cheap and cramped in comparison. As residents abandoned them, cities began to tear blocks down to stem rising vacancy rates in the 2000s. Those who remained were often the residents who could not afford to leave or who were too old for it to be appealing. With increasingly unstable social structures, Plattenbau neighbourhoods became stigmatised. At the same time, prominent government or cultural buildings had lost their functions with the collapse of the GDR economy, and many were demolished and replaced with buildings that fit the image of a capitalist city centre. The demands of the new economy had left East German modernism in disgrace.

This was the context into which many of today’s Plattenbau Instagrammers were born. As a child, Liesbeth Charlotte Werner would often tell her parents and grandparents she thought Plattenbauten were beautiful. “They would always respond: ‘How can you find that beautiful? It looks so ugly!’ I never understood that,” she says. Though the 20-year-old photographer does not live in a Plattenbau, her grandmother and many of her friends do. She grew up surrounded by them in Chemnitz, a small East German city with an impressive ensemble of modernist architecture and a 40-tonne bronze bust of Karl Marx in its centre. Werner says she has fond memories of her grandmother’s building. When she visited, she would often go play with the neighbouring kids in the courtyard.

Mainstream taste among young people would probably still condemn the Plattenbau, but the ranks of their proponents are growing. In some ways, the trend is predictable. Arnold Bartetzky, an art history professor at the University of Leipzig, says it is a typical result of generational change. After 20 years, buildings tend to be perceived at their ugliest. That begins to change when they turn 40 or 50, he says. In the latter half of the 20th century, the generation whose parents were busy building Plattenbauten began to fight for decaying pre-war tenements. For them, modernist concrete was destroying the old structure of the cities they had grown up with. But for the 20-year-olds of today, GDR modernism is part of the historic urban fabric.

In the 2000s, small initiatives began to 24 oppose the demolition of individual GDR buildings. These were led mostly by art historians or people in similar professions, many of them from the east themselves. They argued that those buildings had design merits worth preserving, says Mark Escherich, a preservation specialist at the Bauhaus University in Weimar. Conferences followed, and artists started making work in and about GDR modernist buildings.

In 2005, then architecture student Martin Maleschka, 38, began to photograph buildings and public art in his hometown of Eisenhüttenstadt as it experienced a wave of demolitions. At the time, his work mostly met scepticism. But as time passed and GDR structures became rarer, his audience grew. “For me it’s totally astounding that people born after 1990 are also interested in the topic,” he says.

Yet the younger fans of Plattenbauten often approach GDR modernism without the same emotional attachments as their parents, says Christoph Liepach, a photography student who runs an architecture publishing house in Leipzig. They are like outsiders, able to look at architecture without emotions driving them to either love or hate it, he explains.

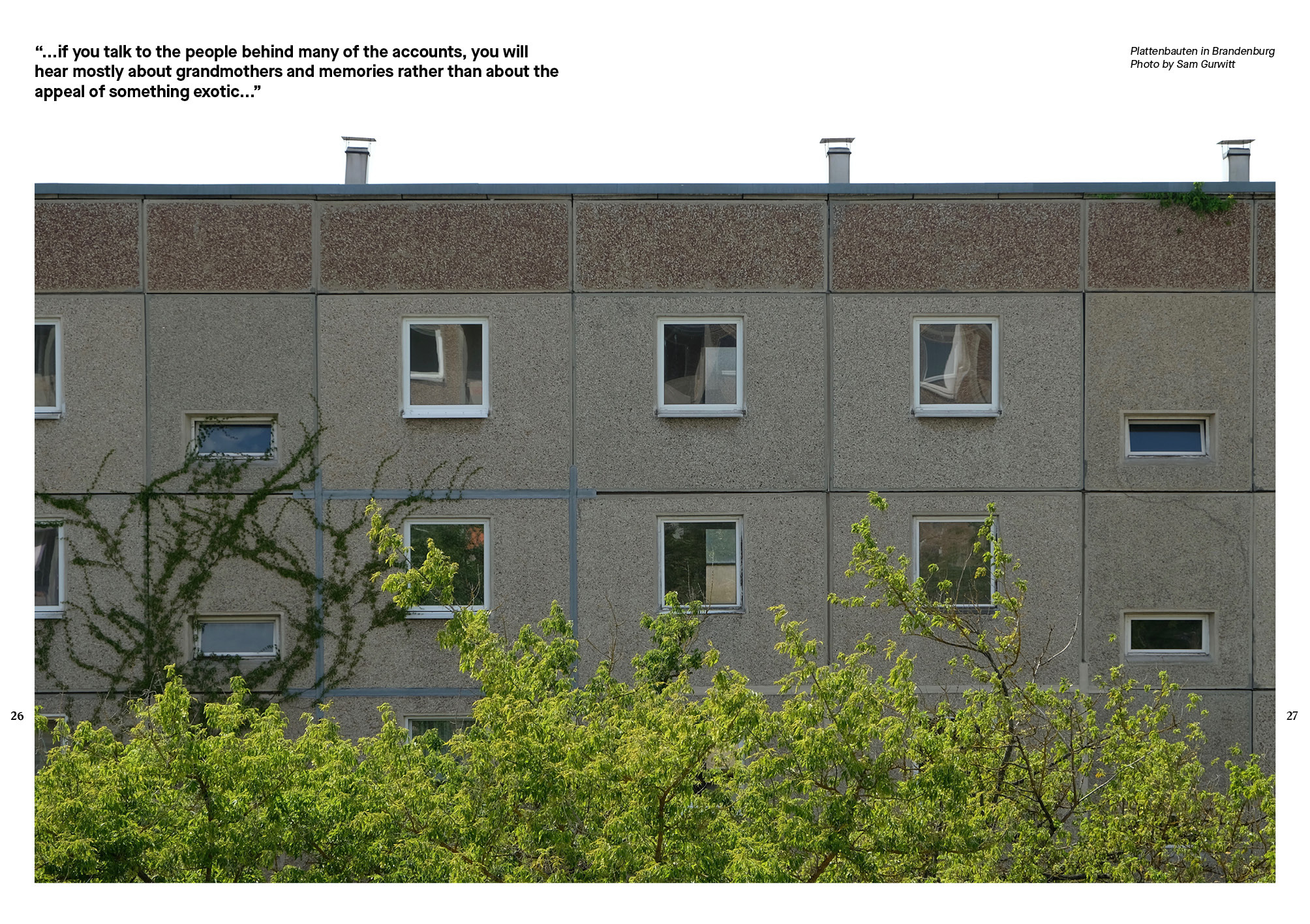

When you scroll through photographs of dusk-tinged concrete walls tagged #plattenbauromantik or #ostmoderne on Instagram, it’s easy to assume the trend is a fad of Berlin hipsters with bulbous wire-rimmed glasses and fetishes for concrete. But if you talk to the people behind many of the accounts using those hashtags, you will hear mostly about grandmothers and memories rather than about the appeal of something exotic.

Rogowski says she likes to play with “nostalgia” in her photos. People a few years older than her shun that word. In the 1990s, Ostalgie—a play on the German words for “east” and “nostalgia”—was often used derogatorily to refer to East Germans who wanted the GDR back, or to the kitsch trend in which East German products were sold as souvenirs. But Rogowski is not afraid of similar accusations. She believes she is way too young for her emotional attachments to gesture at the GDR itself. “For me it has nothing to do with some kind of pride but is rather simply nostalgia: Ifeel at home. It reminds me of childhood.” With her Instagram account, she wants to show “that Grünau is not just the decaying fringe of Leipzig,” she says, “but much more.”