War blurs professional boundaries; it is all about survival. Yet, many Ukrainian artists stay true to their identities and pick up brushes in the face of the Russian invasion.

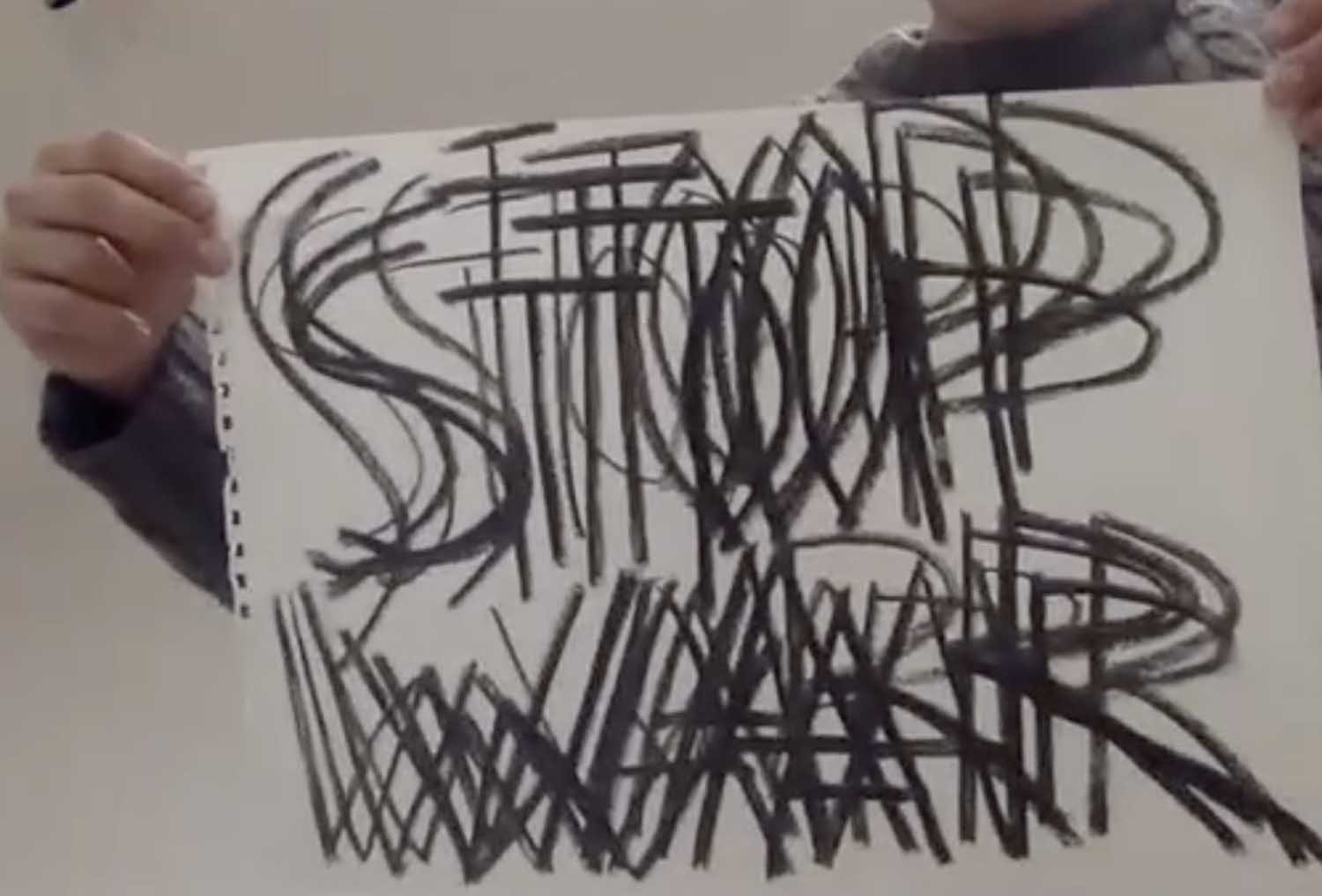

Sitting in the basement of the Voloshyn Gallery in Kyiv, visual artist Nikita Kadan has made copies of one particular artwork ever since he took refuge in the same space that served as a bomb shelter during the Soviet era. Kadan repeatedly scribbles “stop war” in charcoal strokes on cartridge paper from his sketchbook. “It’s like a magic ritual,” Kadan says. “You repeat it again and again and again, and nothing changes. Yet each day brings new dead bodies.”

Kadan is a part of the new generation of Ukrainian artists who interweave art and activism in their work. He is one of the pioneers of Revolutionary Experimental Space, a forum for artists protesting the Russian intervention in Ukraine through arts since the Orange Revolution—a series of protests in the wake of the contested presidential election result in November 2004.

Kadan’s slogan may be commonplace—echoing on social media and protester’s placards—but it is a part of a more extensive body of art that will keep the memories of the war in Ukraine alive. Against a background of air raid sirens and incoming missiles, it is not easy to create art. Yet, Kadan absorbs his fear as he paints with resolve. These Ukrainian artists face an unavoidable decision: either take up arms and brave the battlefields or hold up the paintbrush and colour the canvas red.

From post-apocalyptic opera to reality

Before the war, the arts scene in Ukraine was thriving, with young artists using the Soviet past to depict anti-war rhetoric in their work. Just three months ago, Ukrainian composers Roman Grygoriv and Illia Razumeiko were smiling and posing at the awards ceremony of the Great Real Art Festival in Kyiv, celebrating the listing of their opera, Chornobyldorf, among the six best operas and musical theatre performances.

The opera features a post-apocalyptic story set in the next millennium. Inspired by the Chernobyl and Zwentendorf nuclear plants in Ukraine and Austria, the award-winning opera asks what would happen if human civilisation disappeared in the face of a nuclear disaster and only fragments of people remained.

Little did the composers know that the horrors of the post-nuclear world they depicted so theatrically would become real concerns in less than three months. On 4 March, Russian forces attacked and took siege of Europe’s largest nuclear power plant, Zaporizhzhia. Despite the shelling of the power plant, a fire in an administrative building and combat on-site, there has been no nuclear fall-out. But many fear the possibility.

As Grygoriv sits in his house in Ivano-Frankivsk, a city perched in the picturesque Carpathian Mountains in western Ukraine, only sirens interrupt the eerie silence outside. He no longer identifies as an artist but as a fighter.

“I want to take up arms and fight,” he says, with an expression that reverberates anger, nervousness, and weariness—all at the same time. However, the creative urge in him is hard to abandon. For many artists, their craft remains their primary means of resistance.

On 20 March, the two composers were expected to perform parts of Chernobyldorf in New York as part of the Ukrainian Contemporary Music Festival. While the duo were unable to fly to the US, a 45-minute video clip selected from their recent seven-hour-long performance—titled “Mariupol”—was featured at the event. This composition is dedicated to its historic namesake, where 80-90% of the buildings have been damaged or destroyed by Russian artillery, according to city officials.

Sorrow and pain can be felt in Mariupol, both in the composition and in the remains of the city. Against a dark background, Grygoriv and Razumeiko can be seen playing a microtonal bandura and cymbal piece for seven long hours. Even for a foreign audience, it is evident that the powerful reverberations of the instruments are nothing short of a strong message of resistance, sorrow and agony against the war.

The entire composition was broadcast on Vehza, a local radio station. The funds raised through the performance went to humanitarian aid.

Showing vulnerability

At Ivano-Frankivsk, which lies over 600 km away from the capital city of Kyiv, artists are uniting to fight the war through a novel approach—raising funds by selling art and preserving artefacts that represent their history and identity. The city adopted its present name in 1962, honouring Ivan Franko, a poet and founder of western Ukraine’s socialist and nationalist movement. In the last half of the 20th century, it became one of the seats of postmodern art in Ukraine. Today, the city symbolises Ukraine’s resistance through the arts.

Local art curator Anna Potyomkina wants to establish a small residency for artists. But finding art supplies is not easy in wartime, and plastic has become a replacement for canvases. Potyomkina decided to stay in Ukraine despite the war but has now shifted her work from promoting art to preserving it. As families, including artists, continue to flee their homes, Potyomkina helps preserve their archives. The artworks are temporarily kept in an underground room with good ventilation, while Potyomkina and her team try to arrange transport. So far, she has had little success.

“Just like people die during a war, art gets destroyed. And this art represents culture. We want to protect it to protect our identity,” says Potyomkina. “Art is an important part of the human code that makes up a whole nation,” she adds.

Despite Russian bombs killing civilians every day, for most of the artists in Ivano-Frankivsk, the narrative is not anti-Russia or anti-Putin. “It is mostly about the hardship they see around them,” says Olga Dietal, co-founder of Proto Produkciia, an art management firm. “In these artworks, they depict their vulnerability and resilience.”

Black shadows on a rich soil

A day before the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, Ukrainian-Russian artist Aljoscha staged an anti-war intervention in front of The Motherland Monument in Kyiv. He stood naked in front of the massive statue at the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War. While the statue holds a shield bearing the hammer and sickle of the Soviet Union, Aljoscha held up an abstract pink shape fashioned out of acrylic, plastic and fibreglass. The performance symbolised the vulnerability of being attacked without protection—in a place that once memorialised the Russian Red Army.

In his basement in Kyiv, Kadan tries to express the contradictions of the war through art. “Russia itself was built on the principles of anti-fascist rhetoric, but has now become a symbol of extreme nationalism, homophobia and racism.” In his charcoal painting, the visual artist represents this irony through what he calls the “universalism of deaths.” He draws black shadows on the soil. “This could be the body of a Ukrainian victim of Russian shelling,” he explains, “or the body of one of the 19-year-old Russian soldiers who has seen very little in his life, who was sent to Ukraine and finds his death. This rich Ukrainian soil buries the bodies of both.”

Ironically, the Voloshyn art gallery sits in the same street as the Museum of Russian Art in Kyiv, which holds more than 12,000 pieces of art—the most extensive collection of Russian art outside of Russia. The museum staff now sleeps between the sculptures to protect the artwork from looters, hoping to transport them to the relative safety of western Ukraine soon.

In many—if not all—conflicts, from Syria to Ukraine, artists face difficult choices, explains Kadan. On the one hand, there is an urgency to act in the here and now, to be clear and understandable. On the other hand, the real power of art lies in its depth of reflection, for which war doesn’t afford much time or space. “Maybe balancing these two aspects is our new challenge. We’ll have to create new meaning through this paradox,” he says.

Despite all the hardship, the artistic spirit lives on in Ukraine. Chornobyldorf was planned to be performed in Kyiv on the 17 May, followed by a show in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, Vienna in Austria, Gdańsk in Poland and Huddersfield in the United Kingdom. Despite the bombs flying, the producers of Chornobyldorf hope the show will go on as scheduled.