“That’s crazy,” I say while holding a sign reading “Stop Putin’s War” outside the Russian Consulate in Naples. “I’ve lived outside of Russia for years but my insides still twist every time I see the police coming my way.” Some of my Russian friends nod while the Ukrainian part of the group remains diplomatically silent. It’s the first day of the war that our country started against theirs.

After Putin’s “Slavic history” speech on the night of 21 February, I went to bed in tears brought on by disgust and fury. It was evident from his imperialist words that another war would happen, following in the list of Chechen, Georgian, Crimean and Syrian conflicts I have seen in my short life. The invasion of Ukraine began two days later.

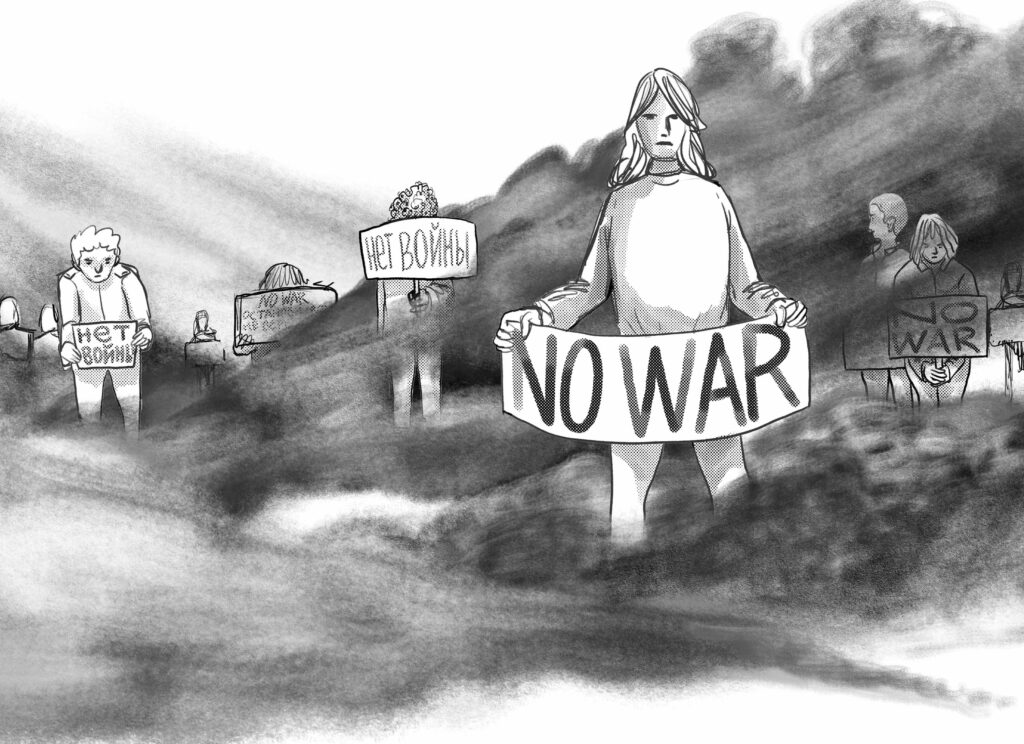

My friend and I agreed to organise a demonstration outside of the Russian consulate in Naples with a mixed group of around 20 Ukrainians, Russians and Belarusians ready to protest. We stretched out in a long line holding our signs. Locals in the buildings across the street smiled at us while finishing their late lunches or starting their aperitivo—some Italians stopped to ask us what had happened. They were still living in yesterday’s peaceful world.

The owner of a nearby restaurant came out with a phone in his hand, took some pictures and made a call. It became all too familiar. “He’s going to tell them to make us leave,” I thought. “The Italian police will come and check all of our documents. They’ll say that we’re foreigners here and not allowed to protest. Could they send us back for something like that? Oh, the paradox of being sent back to a regime you’re against—for thinking you have more human rights abroad than in your birth country.” A grey car pulled up a few minutes later. Two men climbed out of it, turned to face us and stood there, watching.

Someone in the group started fidgeting. Many of us were trying to remind ourselves that we were in a country where you could still state your opinion. Images from my previous life kept rushing through my head. I remembered the head of a Moscow protester bobbing on the ground as he was beaten up by Rosgvardiya soldiers—the national guard that reports directly to Vladimir Putin. I remembered searching for lawyers late at night while my friends sat in police buses. In the last decade, each protest has become more dangerous—with more people attending and more thuds from batons meeting human flesh.

In Naples, a huge crowd was waiting for FC Barcelona to arrive at a seaside hotel nearby, so we decided to move there. The grey car kept following us until we stopped at the main square. It parked nearby while we recreated our protest line across the piazza. Two casually-dressed men came up to us and asked what our intentions were. “We are from the local police,” one of them said. “We came to make sure you stay safe and nobody attacks you. Do you want to move to the other street around the corner? We heard there are more journalists over there.”

I exchanged puzzled looks with my friends, some of them holding back tears. We truly weren’t in Russia anymore.

On the streets in Moscow

Back in Russia, people protest on the streets, too. Alena Mikhina is a biologist who grew up in Russia but lived in both Prague and Strasbourg during her studies. She spent the last six months in Moscow and went to all the opposition protests she could. “From the first days of the war, the detentions were really violent,” she says.

First off, the police would stop many people on the subway to check their phones for anything they label as treason. Alena got arrested for the “no war” embroidery on her backpack. “Most of the people with me in the police bus didn’t even manage to unroll their posters or start chanting before they were detained,” she says. “There were also some random passers-by who were taken into custody by mistake.” When the group arrived at the police station, the female officers were the most aggressive ones. “They were screaming and threatening to use the submachine guns that were hanging off their shoulders. They wanted to scare us and make us forget our rights.”

Alena struggled throughout her arrest. “They wanted to take my fingerprints and headshot. Some officers wanted to hold me in place for this but I wriggled away and repeated that they can’t use physical force. The fingerprints turned out smudged so it all circled back to yelling.” The police slowly went through all of the personal belongings in Alena’s backpack—taking each small item out, mocking it and throwing it around the room. The ordeal went on for hours. “This was not my first contact with the police, but it was still humiliating and exhausting,” she says.

Finally, Alena’s arrest was registered as an administrative case. She received a €200 fine but would face a minimum of 10 years in prison if arrested again. “The police made sure I understood and paid a visit to my brother’s house to repeat this. You realise that you stand in front of a colossus of a regime that will crush your bones to dust. I tried to go to a protest again a week later, but I saw police buses everywhere when I was leaving the subway station. People were being taken away left and right. I understood that I would never be able to leave Russia if I went to the streets that day. That’s when I turned around and got back on the train.”

Judged for Putin’s decisions

Since the beginning of the war, I have been asked why Russians don’t protest more often. “How come 83% of Russians support the war?” they would prod. Both of these questions take me aback—decades of internal Russian repression are not taken into account.

The sociological surveys that provide these statistics have been a propaganda tool in Russia for the last 15 years. They isolate the opposition and give them a feeling of estrangement from the majority. By making people feel that there are not enough of them to demand change, authoritative regimes rob the population of their voice. In fact, there are no independent sociological institutes left in Russia at the moment that could paint an objective picture of the anti-war movement.

The regime wants to make you feel that any attempts for justice are useless. It intends to make you passive through fear. But that passiveness prompts many “silence is violence” posts on social media from those who want Russian citizens to speak up. “I feel isolated,” Alena sighs. “It’s impossible to explain how hard it is to have an organised protest in an authoritative regime where independent media is shut down. You end up being left out of Russian society because you’re not afraid to actively show your disagreement, and out of the European one because people think that the dictatorship is there just because we never protest. In the end, you end up with only a small group of people who share your views.”

My former colleague Olga* shares this feeling just a day before she has to appear in court for “Discrediting the Russian Army.” A new law, enacted on 4 March, punishes citizens for protesting or posting on social media against the war. “We’ve been protesting together since 2013,” she says. “But there are many more Rosgvardiya than us. I was going out to show my Ukrainian friends that they are not alone, that Russians are taking to the streets. I wanted to put my whole life at risk. But I understood that my child would stay behind, all alone. My self-destruction will not solve anything because mass movement is killed by the regime. I’m ready for my generation to be judged for Putin’s decisions—I guess that’s inevitable. I can’t help but worry if my child will be judged for it, too.” Still, Olga tries to do her part and helps her Ukrainian friends get their families out of the country.

When activists and journalists are facing one arrest after the other for years, when the police come to pressure people’s families, when national treason laws get additional articles every month—the active part of society loses motivation. Many now say that they don’t want to spend their whole life in jail far from their kids. The morning after our interview, Olga asks me to delete our Telegram chat, knowing that her phone will be searched again in court.

A space to grieve

Protesting together—Russians and Ukrainians—the past few weeks has made me realise how much we can achieve side by side. The activists from Ukraine feel righteous when speaking up. It can be very therapeutic for Russians who, before arriving in Europe, had seen only police buses and extremism charges after demonstrations.

Protesting alongside Ukrainians does not just give Russians the possibility to create a new, more positive experience where speaking up is not punished, it also keeps us in touch with reality on a daily basis. Volunteering at refugee centres, helping friends find accommodation for their families fleeing the war, listening to the stories of protesters who came from Mariupol a week ago—we cannot hide from this by turning off our TVs or logging out of Facebook. It is a complicated knot of emotions where our Ukrainian neighbours have both the space to grieve and to feel resentment towards what our country is doing.