If there is one thing that was not spoken about around the dinner table when I was growing up, it was the European Union. Being born in Norway just after the referendum on membership in 1994—the result of which was 47.8% for and 52.2% against—the EU felt foreign to me, and the topic settled. The only other time the country voted on the matter was 22 years prior, in 1972.

It has been 28 years since the last referendum, and since then Norway has not seen a national debate on EU membership. Because voters would have had to be 18 years old to take part in the last referendum, no one born after 1976 has had the opportunity to cast a vote on whether they want their country to be integrated into the EU.

“Whole generations have missed out on a debate that could have enormous implications for their lives and future,” says Solveig Evensberget, a 27-year-old Norwegian political scientist. If there was any discussion about the EU in any setting, the most common story told was that the rest of Europe would “take all our oil and fish” (Norway’s largest exports) and that Norwegians should be happy they weren’t a member. “Good thing those referendums in 1972 and 1994 settled that matter for good,” the common narrative would go. Case closed.

“Since then, the situation in the world has changed,” says Kjetil Hansen, 28, a teacher in Tvedestrand in southern Norway. “Now, we can also look at the experiences of our neighbours, Sweden and Finland.” The two Nordic countries decided to join the EU the same year that Norway said no. “We can see how membership has affected them,” Hansen says, “for better or worse.”

Amidst recent global events, from Covid-19 to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Norwegian youth are beginning to engage with the topic that has been gathering dust for decades.

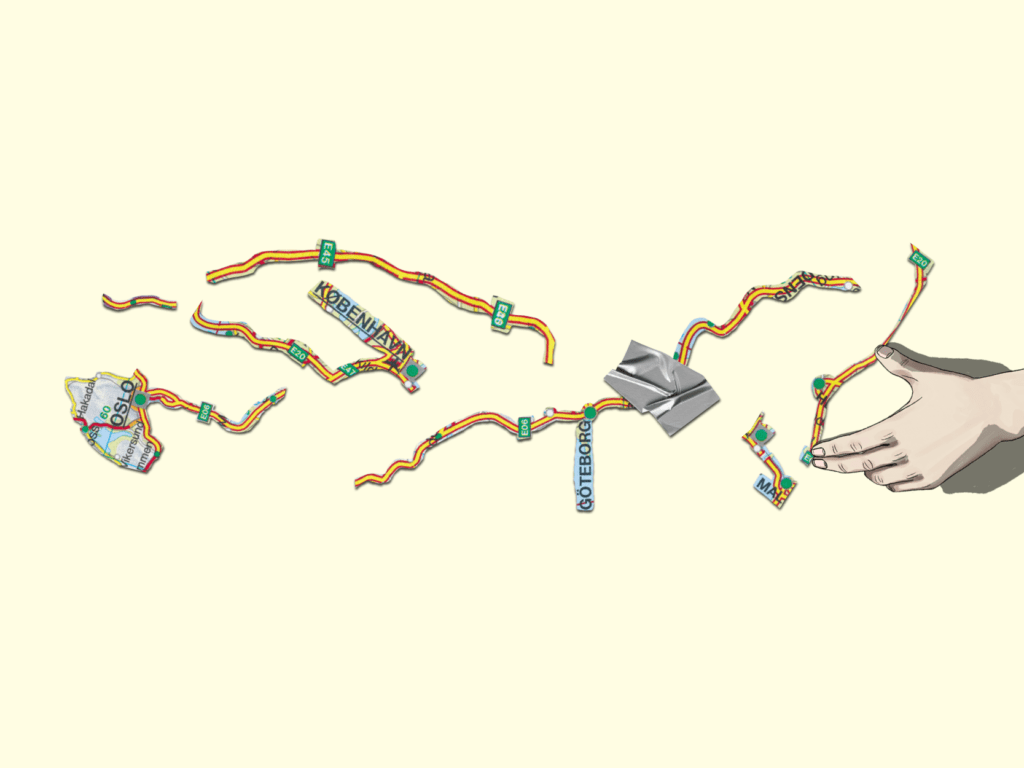

A pseudo-membership

Instead of joining the EU, Norway joined the European Economic Area (EEA) in 1994, along with Switzerland, Lichtenstein, and Iceland. The country has gained many benefits from this agreement: access to the EU’s internal market, freedom to travel, work, live, and study in the Union—even the ability to participate in Erasmus programmes—while granting some exceptions from certain policies, such as trade, agriculture, fisheries, and customs.

But even though Norway follows hundreds of EU directives thanks to the EEA agreement, the country has never once had a seat at the table in Brussels. When asked about Norway’s role in these political decisions, Solveig Evensberget called the country’s absence “basically undemocratic”.

“The Norwegian people should be informed and enlightened, and we should have an opportunity to take part in the decisions concerning us as a society,” she says. In her opinion, this includes the EU directives that Norway follows.

The topic of Norway’s relationship with the EU has slowly started entering household conversations and mainstream news in the last two years, largely due to the Covid-19 pandemic. With the EEA Agreement, it was not a given that Norway would be part of the EU’s vaccination scheme. In fact, the Norwegian Coronavirus Commission recently gave credit to Sweden’s vaccine coordinator for getting Norway included through bilateral agreements.

“Covid-19 probably showed us that it is not so beneficial to be standing outside of the cooperation, as we were not being prioritised as much as EU countries,” says 30-year-old Simen Strand-Pedersen, a publishing assistant based in Oslo, Norway.

Another factor influencing the rising interest in EU-Norway relations is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Because the country doesn’t take part in any EU security cooperation, Norwegians look at their border with Russia with new concerns. Some question whether security cooperation with the EU, in addition to Nato membership, could be a good idea.

The topic has now moved onto the political agenda. Norway’s largest opposition party, the Conservative party, Høyre, has always had a pro-EU stance but had not actively advocated for Norwegian EU membership after 1994. However, at the party’s national conference in April 2022, the party passed a proposition saying that they will call for a new Norway-EU debate.

But a call for a debate by a leading political party in Norway is no small matter. In general, Norwegian society can be characterised by a large trust in public institutions, the media, and politicians. A new debate would likely follow an official pattern, as past processes have: involving assessments of the consequences of membership, and official debates with all political party leaders aired by public broadcasters.

“I believe this discussion must happen in Norway now that Europe and the EU are changing very rapidly,” said Ine Eriksen Søreide, a leading politician in the Conservative party and former Minister of Foreign Affairs, after the conference. Other parties, such as the Centre party, Senterpartiet, which is currently in government and traditionally the biggest political opponent to Norwegian EU membership, quickly opposed the need for a new EU debate. The next national election takes place three years from now and would be the next opportunity for the Conservative party to act on their newly adopted EU initiative.

To debate or not to debate

After the Conservative party’s decision, people were confronted with the question of EU membership once again—or among my generation, for the first time.

The debates surrounding the past two referendums were probably the most disputed political issue in the country since World War II, creating divisions in society. Some policy areas that were especially contested were related to agriculture and fisheries policies, as these are important sources of income in rural areas. Now, some question whether the country should reopen a topic so divisive—and the old argument of “they’ll take our oil and fish” still resounds throughout the country.

A recent survey, shared by Norway’s public broadcaster NRK on 7 June 2022, showed that 35.3% of respondents would vote yes to EU membership. This is only a third of the respondents, and some argue that this lack of majority support for membership is a reason to avoid reopening the debate. But without the space to learn about the issue, some young Norwegians have not yet had a chance to form their own opinions.

“I don’t think most people know what the difference would be if we joined,” says Simen Strand-Pedersen. “The EU doesn’t fill that much of the news, so it’s not something I really think about. I would have liked to see a debate, so we can weigh the advantages and disadvantages.”

This sentiment was echoed by Kjetil Hansen. “I want Norway to have a good relationship with the EU,” he says. “At the same time, it is difficult for me to answer whether we should be members. Brexit showed that not all member states are equally satisfied, and there is often talk of how much the EU should govern.”

Political scientist Solveig Evensberget is one of many young Norwegians who are increasingly calling for a debate. “Today’s challenges are too great to be solved on our own,” she says. “I think it’s an overly-accepted attitude in Norway that we can manage things alone.” Some millennial politicians agree with her. Guri Melby, parliamentarian and leader of the Liberal party, Venstre, opened up about her personal views in a commentary piece in November 2021: “On the 28th of November 1994, I was 13 years old. The adults got to give their opinion in the polling stations that November day. My generation did not.” The politician hopes to hear new voices speak up. “Next time, it will also be the young people’s turn.”

In the past, many political parties making up governing coalitions have included a so-called “suicide clause” into their agreements. If one party in the coalition were to officially initiate a new EU debate, their agreement would break. That is how set-in-stone the EU matter is in Norway: governments would literally fall and a new government would have to be formed. Furthermore, the issue does not follow a traditional left-right divide. Parties that agree on many things can disagree completely on this point, which begs the question: will Norway ever have a governing body that would survive long enough to see this debate through?