Questioning the use of language is an integral part of the work we must do to undertake journalism ethically. Though this issue primarily touches upon drugs that do not take space in the public discussion around drug use and addiction, we felt it was essential to investigate how our understanding of substances and those who use them are shaped by stigma. Our value systems influence our language—by changing our language, we can try to improve the current public discourse.

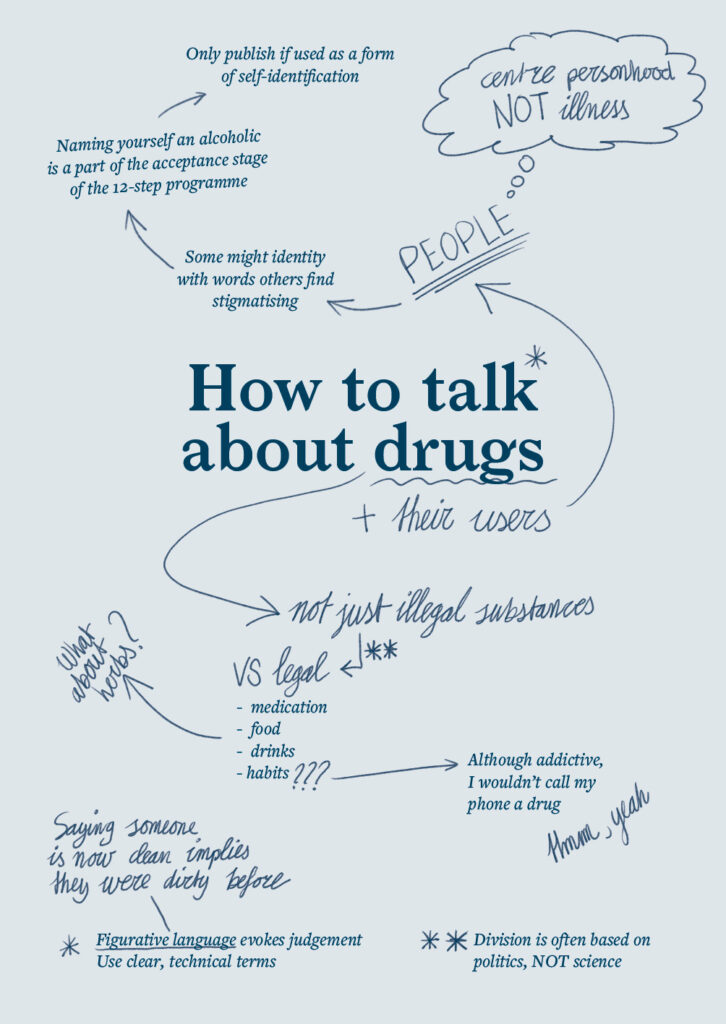

When we talk about “drugs”, we usually mean controlled substances. But drugs are all around us, and not just in our medicine. The division between legality and illegality is oftentimes based on political interests rather than scientific facts.

Why we use person-first language

We do not want to deny the humanity of people who use drugs, and one way to do this is to centre their personhood as opposed to their illness. Independently of what people may refer to themselves as, we—as a media outlet—strive to use language that separates the person from their condition.

At the same time, terminology should not be only a matter of top-down creation. People with substance use disorders and those recovering may identify with stigmatising words. Naming oneself as an “alcoholic” is part of the acceptance stage of 12-Step programs. This may be hurtful to some, but useful to others. People who use drugs can determine on their own terms where using stigmatised words is appropriate.

Example: not “addict” but “person with a substance use disorder”

Why we don’t use idioms

Figurative language often evokes judgement and prejudice, especially when it comes to the war on drugs. We choose to use clear, technical terms from which one meaning can be derived, without any inference from the position of the reader. This also reveals the imbalance with which we regard drug use, with multiple commonly-used slang words for certain types of drugs, and none for others—like nicotine or caffeine.

An example? Don’t say “pothead” but a “person who uses cannabis”. Similarly, saying someone is “clean” implies that they were dirty otherwise.

“The words we use to talk about drug use and people who use drugs matter. Because the lives of people who use drugs matter.” – writer and activist Ray Mwareya

Why we believe all illnesses are equal

The language around drug use is often centred on personal failings. People’s humanity is stripped away, leaving room for little nuance. Illnesses, when perceived as being out of the affected person’s control, are treated with kindness and understanding. Developing and pushing forward a better understanding of who we see as being in control or at fault when it comes to addiction is essential if we want to destigmatise addiction. There are well-documented genetic and social factors that impact one’s predisposition to developing an addiction. When we see addiction as a personal failure of willpower, we conceal the ways in which the lack of mental health care, affordable housing, and social services in our societies fuels rates of substance use.

Why we should all work on this together

How can you communicate better, you ask? In A handy guide, Harvard professor John Kelly created an ‘ad-dictionary’ with terms surrounding substance use, flagging certain expressions such as abusers with ‘stigma alerts’. By knowing how to address these topics better in our everyday conversations, we can work towards change together.