Buildings keep us warm, allow us to gather, and are often sites of idea- generation. They are places of residence, comfort and safety. But they come at a huge environmental cost. The construction industry accounts for 38% of global energy-related CO2 emissions—11% of which results from producing brand-new materials such as steel, cement and glass, according to the Global Alliance of Building and Construction.

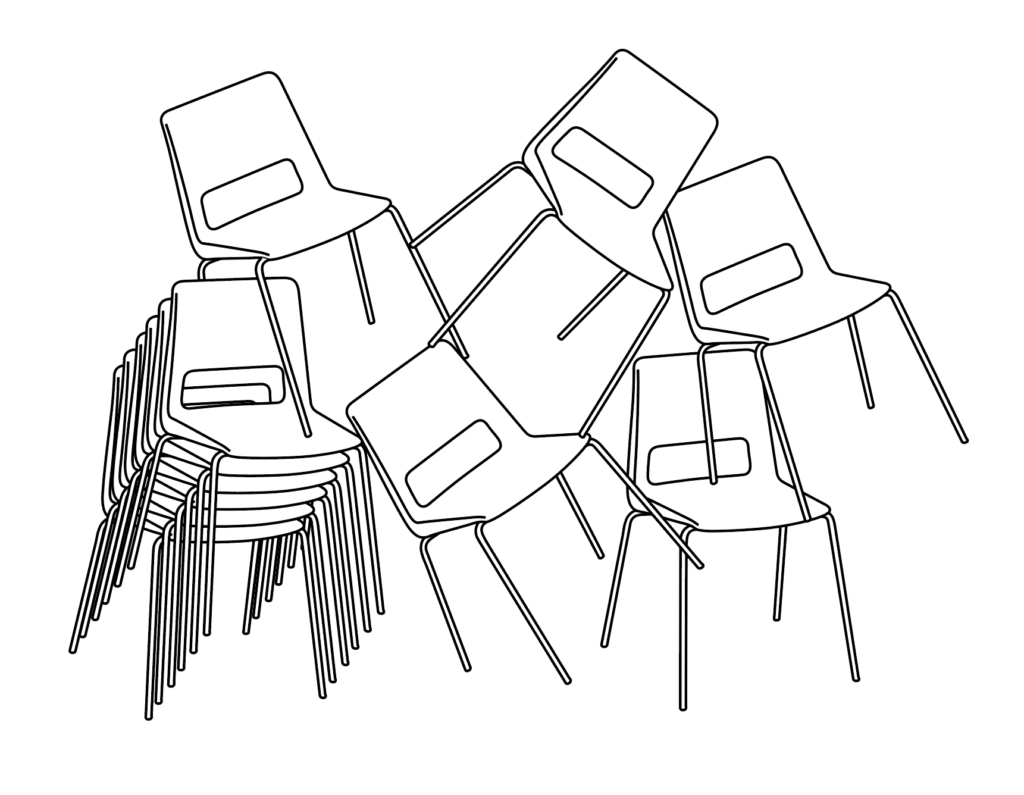

Some architects are taking a different approach. Instead of building with raw materials extracted from the earth, they’re using what we have in abundance: waste. One example is Stian Rossi, an Italian-Norwegian architect at architecture and design firm Snøhetta. In 2019, Rossi worked with Norwegian furniture-making conglomerate Nordic Comfort Products (NCP) to remake its R48 classroom chair, a design classic, using 100% recycled plastics from Oslo’s fishing industry. The practice is now embedded in its production process. NCP converts worn-out fishing nets, ropes and pipes from local fish farms into tables and chairs for schools and offices.

This example, Rossi believes, is a starting point to create a wider narrative. “You can’t just do something niche, it’s never going to be enough,” he says. “You have to go in at industry level at work at scale.” Rossi has shared his knowledge of building with waste materials with several organisations. He is convinced that if architects partner with companies as “experts, consultants and creative collaborators,” they have a chance of popularising new techniques and planet-friendly materials.

Rossi is not the only architect on a mission to make their field more sustainable. In the town of Sinandro, Italy, design studio GISTO turned structural elements of a former military base destined for demolition—including ventilation fixtures, air duct covers and kitchen hoods—into tables, partitions and shelves for the Multiplo research project. In London, design studio GoodWaste collaborated with department store Selfridges to transform its scrap wax, steel and acrylic into lamps, candles and vases. Barcelona-based startup Honext has developed a sustainable building material by combining enzymes and cellulose taken from the waste streams of paper production.

Using waste as a resource challenges the conventions of architectural design. Traditionally, architects learn to make use of scarce natural materials without questioning their environmental or social impact. They rarely stop to think about what alternative materials they could create from waste— that could be more robust, long-lasting or sustainable. This stems from the education that architects and designers receive. “Architects have a superficial knowledge of materials, their properties and the impact they have in the value chain, which is why there has been little innovation so far in producing sustainable building concepts,” says Rossi. “Students get a book and learn the words and the principles and the materials available. But they’re never asked to rethink wood or concrete.”

Lecturing at universities in Norway, Rossi hopes to “switch the mindset” of future architects. For waste to become internalised as a resource in design practice, he believes, it needs to become a staple of curriculums being taught in schools and universities. But this could take time. “Universities are heavy systems. To change them is painful,” says Rossi. We need people brave enough to experiment with materials to find innovative uses for them, and collaborate with others across industries to make them mainstream.

“Part of it comes down to architects demonstrating to others that it’s possible,” says Rossi. “Architects need to be curious about the materials they see in front of them. They should ask themselves, ‘how can I utilise this stuff that we have just lying around?’”