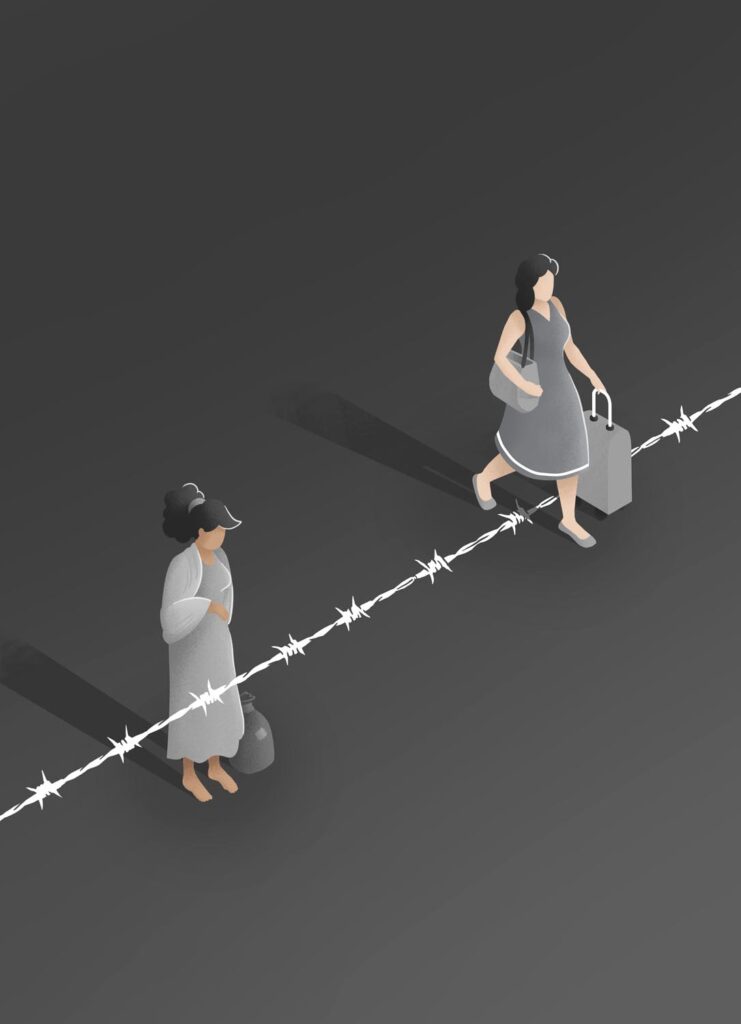

On a Wednesday night in February 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a “special military operation” in Ukraine. Many Ukrainians fled their country, and were welcomed by European Union member states as refugees. Non-white people fleeing the country did not receive the same treatment, leading to reports of human rights violations and racial discrimination in the treatment of refugees. In fact, this was not the first time that non-white refugees have faced racial discrimination on the EU’s eastern borders.

Migrants and asylum seekers from the Middle East have been arriving at the Belarusian border with Poland since July 2021. After Brussels imposed sanctions on the country in the wake of its crackdown on political opponents, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko threatened to “flood” the EU with mass migration. Lukashenko is allegedly behind a scheme involving travel agencies promoting tours with accompanying Belarusian visas in Middle Eastern countries. Similarly, people smugglers are said to be spreading misinformation on how easy it is to enter Europe, as a way to lure migrants to Belarus. Many migrants have fallen into the trap. With the intention to cross into Poland and reach international protection, refugees find themselves stranded in the border areas for weeks because of “pushback policies” deployed by Polish border control and Belarusian officials, who refuse to take the migrants back. Many of those who make it through are detained by the Polish authorities in centres constructed to respond to the migrant crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border.

29-year-old Abdulrahman Saeed Qaid Mahyoub, from Yemen, has been living inside the Polish detention camp for migrants outside the town of Wędrzyn—about 50 kilometres from the German border—for four months.

“I arrived from Azerbaijan on 9 September 2021 via the Belarusian border. Four of us tried to enter Poland, but the border guards caught all my friends and forced them back. They decided to arrest me, taking me to Wędrzyn.”

Erected in August 2021 and run by the Polish border security agency Straż Graniczna, the camp is completely cut off from the outside world. Journalists, lawyers, and aid organisations are not allowed to enter without authorisation from the Polish Ministry of National Defence, and detainees are unable to leave. Nicknamed the “Polish Guantanamo,” the facility currently hosts 321 migrants. That is about a quarter of the total number of asylum seekers who are currently being detained in EU-funded camps across the country. Whilst they wait to be either repatriated or released, they are subjected to all kinds of abuse.

“We never received direct violence from the prison guards, but they treat us like criminals,” says Mahyoub, who decided to leave Yemen, leaving his wife and daughter behind in Saudi Arabia. “We constantly have problems with running water: there isn’t enough for all of us to take showers, or to simply have something to drink.” When it comes to basic medical needs, there is only one emergency nurse. “They kept promising us a doctor would come in every week for treating allergies or infections from the disastrous living conditions, but the guards never gave us a chance to write a formal request.” Mahyoub explained that he experienced sight problems that needed treatment. Unable to access specific medical drops or prescription glasses, the condition of his eye has kept worsening throughout his four-month stay.

Omar Sheikh Zaid, a 30-year-old student, is also from Yemen. He fled the war in his country and entered Poland from Belarus. “Living inside this place is affecting everyone’s future life and current mental health,” he tells us, pointing to the lack of sports facilities, education opportunities, or activities. “Guards rarely distribute clothes and cleaning items,” he says, forcing him and others to ask for these items from outside of the camp. Not to mention privacy issues: “There are only curtains to separate people taking a shower, there is one washing machine for over 120 people in my block, and the rooms [with four bunk beds] are only 12 square metres. What is more, we are given no information about our cases.” The insecurity about one’s status over the course of months, while being forced to share a small enclosed space with strangers, has pushed some to attempt suicide, he says.

As Zaid explains, detainees have limited opportunities to communicate with the outside world. “Each of us can use the internet for one hour every other day, because there are only four computers,” he says. But the connection in the middle of the Polish countryside is usually not very reliable, plus the guards do not speak a good level of English and translation is not guaranteed. Overall, in his experience, “Poland is not a welcoming country for migrants.”

Germany-based journalist Nancy Waldmann was one of the first to report about Wędrzyn in October 2021, having managed to reach the facility on foot through the woods. “Migrants inside have no access to the outside world,” she said, describing the barracks behind a high fence topped with razor wire, men sitting and playing football, watched by uniformed guards. “Conditions are very bad: people are jammed together in small rooms, have no medical or legal aid, and the lack of a common language between migrants and guards makes everything even more difficult to manage.” On 25 November 2021, migrants inside Wędrzyn staged a peaceful protest, demanding freedom or better conditions. Zaid recalls how things escalated when the anti-riot police arrived and charged against the protesters. To defend themselves, the migrants “tried to break through the fence, set fire to various objects, threw chairs, and destroyed CCTV cameras,” reported the Lubuska regional police department.

Among the few people who are able to frequently visit the migrants is Maria. The Polish psychologist, trained in treating Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), lives in Berlin and regularly crosses the German-Polish border to offer her support to the people stranded in the camp. “A lot of those people are illegally detained after they have already suffered torture or violence on their way to Europe,” Maria says. “Many are very sick,” she continues, “and shouldn’t even be there.” But those who manage the facility are probably not even “aware of how tough it is because they are also overwhelmed by their job.” This lack of awareness pervades every aspect of life inside the camp. Maria explains the procedure to identify the age of the men upon arrival: “Anyone without a passport is given the first of January 2003 as their birth date. I noticed there were too many people with the same birthday. How could this be possible? Some of them were really over 18, but others were clearly minors.”

Another regular visitor is Tomasz Anisko, a member of the Polish parliament living in the Lubusz region where the camp is located. He has been fighting to ensure that the migrants’ rights are respected since the camp first opened in 2021. “Conditions there are worse than you would expect in a prison,” he said with resignation. “Migrants are kept there for several months, they don’t know what their legal situation or the status of their asylum applications is. They receive absolutely no information.” Nobody knows “what’s going to happen tomorrow, next week, or next month, and how much longer they’re going to be held.”

Only by 5 November 2021—almost two months after he had entered Wędrzyn—was Mahyoub able to start the application process to gain international protection. “I managed to do so only when I received the support of a lawyer,” he says. “This was not provided by the camp, but thanks to my persistence in reaching out to Nomada.” He is referring to a Polish NGO based in Wroclaw, which provides free counselling to refugees. Feeling violated by these bureaucratic injustices, Mahyoub shares his relief at having finally started his “six-month countdown to freedom” from when they took his fingerprints. The two months he spent inside Wędrzyn before the procedure began never “legally” happened for Poland or for the EU.

Under Polish law, six months is the longest a person can be detained pending the results of their asylum application. However, according to Marta Górczyńska, a human rights lawyer from the Migration Research Hub: “when the repatriation procedure is launched,” meaning that the asylum decision is negative and a person is refused international protection, “then this period can be extended up to 24 months.”

According to the Polish Office for Foreigners, a total of 7,700 applications were filed for international protection in Poland in 2021, representing 0.02% of the Polish population of 38 million. The European Union, through its funding instrument the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF), assigned €115.5 million to Poland during the last budgetary term (2014-2020). This figure, the Office of the European Commission for Home Affairs told us, “has doubled to €236.87 million for the period 2021-2027 to cover the objectives of asylum, integration, return and solidarity.” Part of these funds are directly invested in the management of Wędrzyn.

Out of a total €10.4 million allocated to the facility from the AMIF fund, €7.8 million were destined to the provision of medical services, such as agreement with a doctor and paramedic, purchase of medicines, and translation services for the people inside the camp. This goes in full contrast with what the migrants experience. The Polish Deputy Commissioner for Human Rights, Hanna Machińska, who has visited the centre three times calls in her last report for “increasing the number of psychologists and doctors performing duties for foreigners in the facility to at least two,” because: “Deficits revealed since the beginning of the facility’s existence require actions which will prevent the degradation of physical and mental health of the detainees.”

Khaled is a 27-year-old Afghani programmer and one of the few who was able to leave the Wędrzyn facility after three months to start a new life in Poland. He is still waiting for his asylum application to be approved. Khaled shared his story with us during our visit in Warsaw, where he currently lives.

Remembering how difficult it was for him to “start living after his personal hell in Wędrzyn,” he explains: “When I arrived in Poland through Belarus, I thought, neither of those two countries accept my existence. The camp was no better than the Belarusian “jungle.” They were waking us up every morning at six, just for fun. They did not give us enough time to eat and, above all, they didn’t care if we had any privacy in the bathroom.”

Throughout his stay, Khaled kept in touch with an NGO that helped him out with the bureaucracy of his asylum application. After three months, the authorities released Khaled to a train station with connections only to Germany. A lady from the same NGO helped him find a train that was going the opposite direction, to Warsaw. “Even though Polish authorities treated me like an animal, my intention was to stay here and start over, get a job, and learn the language.” As Khaled speaks, anguish makes way for determination: the desire to “become a useful citizen of Polish society, rebuilding my dignity as a person.”

“We want to be treated like normal human beings, among fellow human beings,” Mahyoub says in a trembling voice from inside his cell. He has not yet been fortunate enough to exit the Wędrzyn facility.

Since the Russian invasion started on 24 February 2022, Poland has received more than 2.5 million refugees from their neighbouring Ukraine by April 2022. Reports of discrimination at the border show that the stance of the Polish government towards asylum seekers from non-EU countries still has not changed. “As a nation, it’s a question of a certain ideology represented by this government and its attitude towards refugees in general, and refugees from Muslim countries in particular,” Anisko, the Polish parliamentarian, explains. “All of the testimonies and recordings of what is happening have to be stored,” he continued, because there will be a time in Poland “when this government will be held accountable for its actions.”

Maria and Khaled asked the authors to keep their surnames confidential.